Advertisement

Commentary

The University And The Battle For America's Political Soul

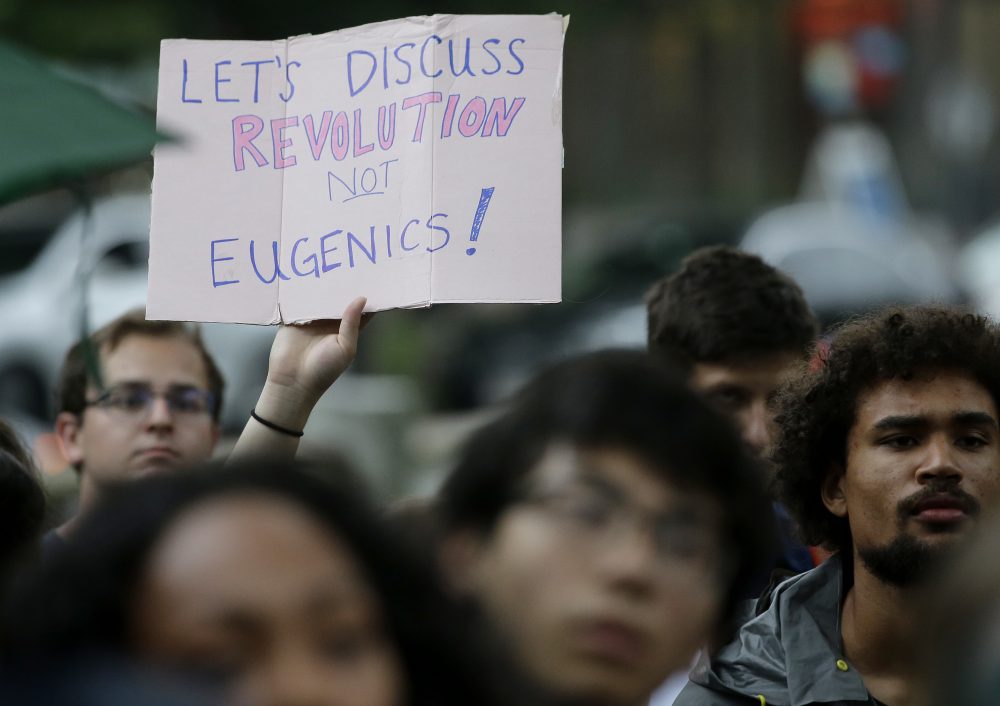

Last academic year produced more student protests than the country has seen since the 1960s. Back then, students worried their universities were perpetuating the same culture of conformity, consumption and authoritarianism they objected to in the government. Today’s undergraduates, by contrast, largely see their universities as safe-havens from conservative ideology, places in which to foment resistance against the systemic injustices plaguing the broader society. This week, a group of students at Harvard gathered to protest Charles Murray's appearance on campus, and Boston area students and professors staged a walk-out in protest of the Trump administration's plan to end DACA. We have only seen the beginning of what is sure to be a monumental year for campus protests.

But as racial, partisan and ideological tensions intensify, it is worth considering the university system’s position in the escalating battle for America’s political soul, and how effectively students can organize under its auspices.

Following the student movements of the 1960s and '70s, American universities reinvented themselves under the new rubrics of equality and justice. Women’s studies departments were born, as were African-American studies and Chicano studies programs. Cultural critics became obsessed with de-canonization, the recovering of marginalized voices, and the rescripting of oppressive historical narratives. But as those in humanities disciplines deepened their commitments to a politics of resistance, society at large marched enthusiastically toward a neoliberal future. The university eventually followed suit.

The financial crisis of 2008 ensured — or perhaps simply revealed — the university’s obligation to the economic survival of American students. Faced with rising tuition costs and an anemic job market, universities doubled down on their commitment to preparing students for lucrative careers. Academic fields that could not justify themselves under these ever-tightening economic constraints were forced to close tenure lines, reduce course offerings, and freeze the hiring of new professors. Between 2012 and 2015, the number of humanities degrees awarded declined by 20 percent, while communications enrollments — the “practical” alternative to a humanities degree — have increased steadily.

The difference between a communications degree and an English degree, however, is stark. A student once told me her communications courses had taught her how to “motivate consumers by manipulating their emotional responses to information.” She was, as a result, very good at identifying when authors were drawing on fear, disgust, desire and delight to elicit a particular response. She was also a good writer and an eager class participant. What she had not yet learned to do, however, was disentangle rhetorical strategies from their underlying intellectual, aesthetic and ideological purposes; she could not differentiate between art and propaganda.

While there is nothing intrinsically wrong with college students opting for majors that train them directly for careers, there is much wrong with the idea that this is the sole — or even the most important — purpose of higher education. It is no coincidence that in the nearly 10 years since the decline of the humanities began in earnest, America has produced an electorate unable to detect and properly respond to the machinations of an unfit and deeply amoral leader. Donald Trump surpassed Hillary Clinton by 4 percent among college-educated, white millennials, the very demographic group the Clinton campaign presumed would carry them to an uncontested victory.

That Steve Bannon’s campaign communications strategy worked as well as it did — and has continued to have such devastating ramifications in the post-election world — suggests that America has become a nation of bad readers. The university, in its inability to protect and defend the value of humanistic discourse, is largely to blame for this.

Until now, universities have attempted to right this wrong by operating as safe spaces from political vitriol, but as the events in Charlottesville remind us, the history and politics of the university are and have always been bound up in the history and politics of the broader society. Giving students a place to safely and collectively air their political grievances away from political vituperation is not enough.

As students return to their campuses this fall, they will return looking for guidance. They will want to know how to engage with the political climate in which they find themselves. They will want to know how to live and work and survive in the presence of people who would seek to annihilate their freedoms. And they will want to know if the universities to which they have entrusted their intellectual development are behind them.

The answer to this question remains murky, as universities continue to deftly straddle the line between placating conservative donors and funding progressive research, facilitating conversation and suppressing hateful language. Though some accommodation is necessary for their survival, I hope to see universities embrace their role as fundamental supporters of student activism. But perhaps, as it was in the '60s, the university functions best as an opponent in the battle for intellectual, ideological and political freedom.