Advertisement

Commentary

The Evil Rising In Europe Is All Too Familiar

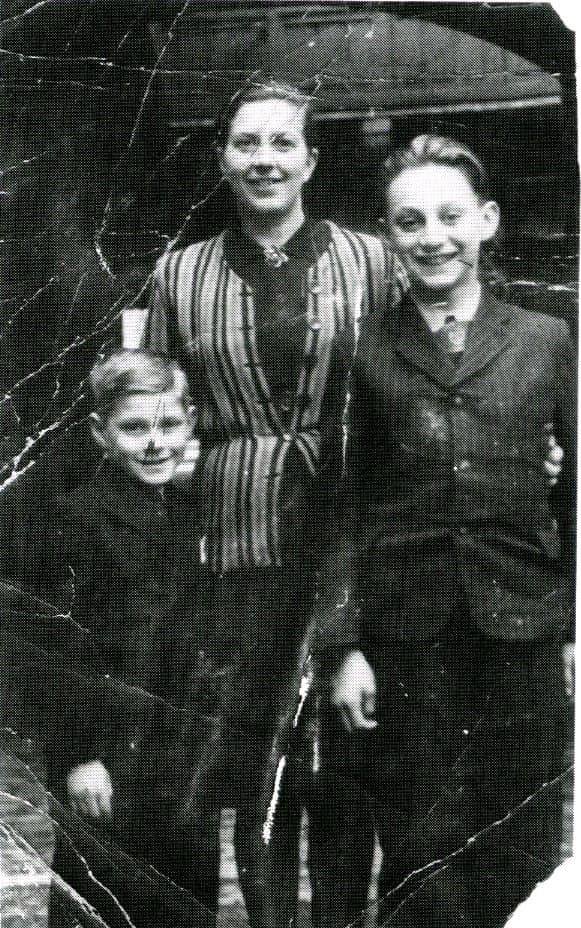

It has been over 70 years since I was forced, as a 9-year-old boy, to flee my home in the Slovakian village of Merašice. In April 1945, I was liberated from Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. What happened there during World War II has haunted me all my life and drives me to bear witness on behalf of all those who suffer as a result of racism and hate.

Each year there are fewer and fewer of us, men and women condemned to have known first-hand the terrors of the past, who are obliged by that knowledge to actively resist and condemn the return of the evil that turned Europe into a wasteland.

After the War, I immigrated to Ireland, where I’ve lived since 1959. Many in Europe today are asking questions that only a few years ago seemed unthinkable. Now it is not at all unreasonable to ask if civil society in the countries that were decimated by the Final Solution are once again being degraded and disfigured by old poisonous prejudices. To answer that question, I was prompted to see for myself the plight of people who are being persecuted — just as I once was — because they “didn’t belong.”

For the documentary “Condemned to Remember,” I traveled again the roads and villages I knew as a child in the depths of war. This time, though, I viewed Europe in the throes of political, economic and social turmoil through the prism of the experiences of an 83-year-old. What I am seeing now in Europe — indeed in too many countries around the world — gives me no comfort.

In Poland, in Jedwabne, at the site of the slaughter and mass incineration of local Jews by their Polish neighbors during the War, I was brought face-to-face with the “crisis of shame” preventing Poles from an honest reckoning with the scale of the local collaboration and collusion with the Nazi extermination project. Tragically, I can say the same about most countries I visited that were once occupied by Hitler’s killers.

In my native Slovakia, I observed at close quarters the alarming rise of the neo-Fascist “Peoples Party-Our Slovakia.” I made several unsuccessful attempts to interrogate the Party’s leader, Marian Kotleba, about his appalling hero worship of Jozef Tiso (and the fascist Hlinka Guard), whose regime was responsible for the roundup and mass expulsion of Slovakia’s Jews into the hands of the Nazis. I never dreamed I’d see the uniforms of the men who destroyed my world on parade again in Bratislava.

Like me they still search for justice and the bones of their loved ones.

Thirty-five members of my family never returned from Nazi captivity. Some were gassed. Some were starved and worked to death. One was guillotined as a partisan supporter. Marian Kotleba hadn’t the guts to meet me. He knew I knew first-hand what his heroes did not only to Slovak Jews, but to all patriotic Slovaks who resisted Hitler’s stooges.

During the trip, my path crossed with Syrian refugees in Germany desperately seeking sanctuary. Seeing them evoked vivid memories of my own days on the run from the Gestapo as a boy. It was easy for me to put myself into the shoes of these “new Jews” of the 21st century. As we talked, me a Slovak Jew, and them, young Kurdish men and Arab women from war-ravaged Aleppo and the hell of Raqqa, we forged an unlikely common bond. We had lost family, survived tyranny and now appreciated every moment of freedom that comes with life in an open, tolerant democracy. Does the Europe they have turned to in their hour of need remember?

Advertisement

My tour brought me finally to Bosnia-Herzegovina in what was once multi-ethnic socialist Yugoslavia before hatred destroyed it. There I recited the “kaddish” at the location of another war crime — the mass murder of 8,000 Muslim men and boys at Srebrenica in July 1995. There I sought out and embraced some of the survivors of “ethnic cleansing.” Like me, they still search for justice and the bones of their loved ones.

I began recording the impressions of my travels in January 2017, on the very day it so happens that Donald Trump was inaugurated as president of the United States. I watched as the successor to Roosevelt and Eisenhower — the liberators of Europe — declared that his priority was “America First.”

What I am seeing, what I am hearing, fills me with dread. And there so few of us left old enough to remember and give witness and warning.