Advertisement

Commentary

The Red Sox Were The Last Baseball Team To Integrate. This Is How It Happened

Sixty years ago this month, the Red Sox became the last team in Major League Baseball to integrate. It was the only team forced to do so by a government agency, and I was in charge of the investigation that led to the momentous change.

In April 1959, the Red Sox had just returned to Boston after their most closely analyzed and controversial spring training in history. It was 12 years after Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color barrier and every other team — some begrudgingly — had followed suit, including Boston’s National League club, the Boston Braves.

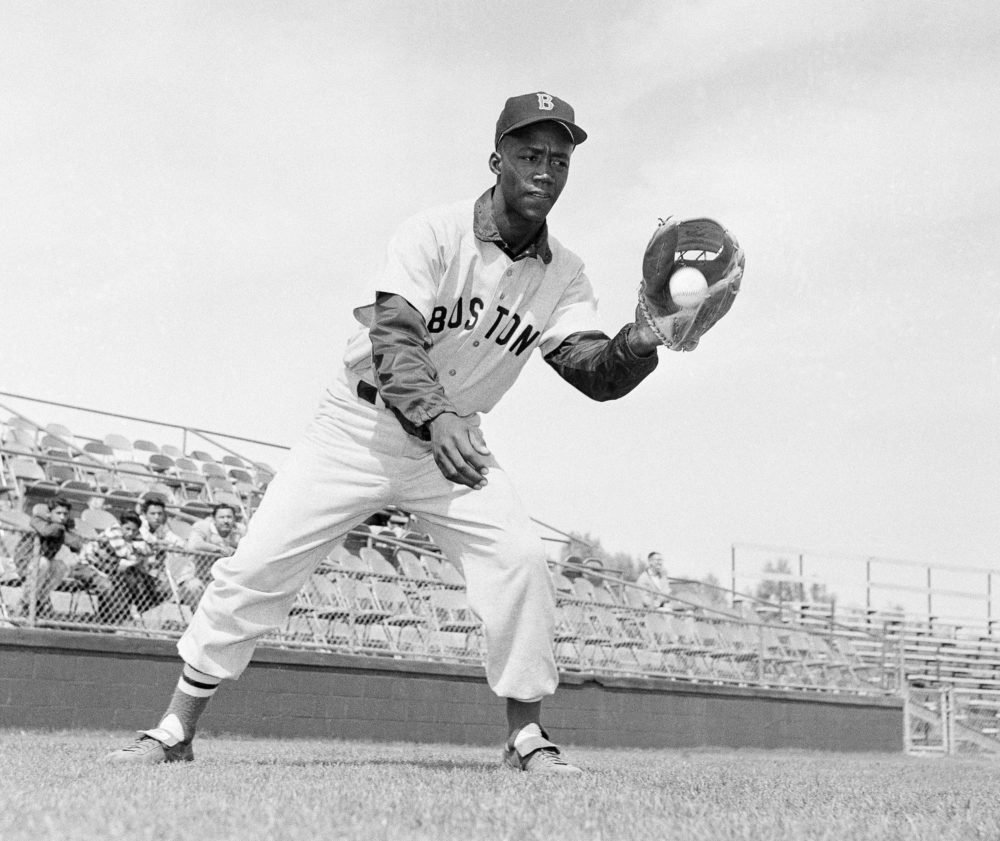

The Sox, however, had stubbornly refused to yield. It wasn’t until rising public clamor persuaded owner Tom Yawkey that the best way to divert his critics was to call up Elijah “Pumpsie” Green from the Minneapolis farm team to join the 1959 spring training squad.

Finally, people hoped, the Red Sox would end their status as baseball’s only all-white team. But the Sox did little to alleviate the humiliation Green experienced off the field during pre-season games in the South and Southwest.

Unlike other major league clubs, the Sox did not insist that Green be allowed to stay in the same hotels as the rest of his teammates. He had to secure his own lodging, often miles away. He traveled through Texas with the Chicago Cubs, their barnstorming partners, who — unlike Boston — refused to bow to Southern segregationist traditions.

Then, at the end of spring training, the Red Sox sent Green back to the minor leagues, despite sportswriters’ general praise of his performance. It was an outrage.

I was 28 years old in 1959 and a member of the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination (MCAD). I persuaded the president of the Boston chapter of the NAACP, Herbert Tucker, to bring a complaint to MCAD, charging a violation of the state’s Fair Employment Law by the Red Sox.

My colleagues at MCAD put me in charge of the case, and I conducted an exhaustive investigation.

My colleagues at MCAD put me in charge of the case, and I conducted an exhaustive investigation. It included a deep dive into the Red Sox’s many refusals to adequately scout black prospects, including Willie Mays (on whom they had first dibs).

I interviewed Jackie Robinson, who told me that the “tryout” he and two other Negro League players had for the Red Sox in 1945 was a sham — and had only been granted after Isadore Muchnik, a Boston city councilor, threatened that the team might lose their license to play baseball on Sundays.

I looked into whether the Sox hiring practices at Fenway Park violated the Fair Employment Law. It turned out they did — big time. With one brief exception, the Red Sox had never hired a black person anywhere in the organization, even in the most menial position.

It also appeared that the team’s racist culture emanated from the top. Tom Yawkey provided financial support to white segregationists in his home state of South Carolina. And Pinky Higgins, the Red Sox general manager, was quoted in the press, vowing “There’ll be no n------ on this ball club as long as I have anything to say about it.”

My investigation showed probable cause of discrimination. The next step, prescribed by MCAD rules, was for private negotiations — but the Red Sox remained intransigent.

The team desperately wanted to avoid a judicial order mandating that they bring up a black player because they feared it would set a precedent for outside interference in their baseball operations. And so, after weeks of hard bargaining — and in spite of my using every one of my legal wiles — the Red Sox refused to sign any public document requiring them to bring Green onto the team.

My colleagues at MCAD wanted a unanimous decision, and they urged me to compromise. I did — but only after receiving a solemn verbal pledge from the Sox management that they would bring Green up before the end of the season. (If they did not, I assured them, they would risk ending up in court.) The formal agreement signed on May 26, 1959, ensured that only non-segregated accommodations would be used during spring training; that scouts would be instructed to act in a non-discriminatory manner and that all scouting records would be made available to MCAD; and that discriminatory hiring practices at Fenway Park would end.

To my amazement, the Red Sox proved better than their word. On July 21, 1959 “Pumpsie” Green made his major league debut with the Red Sox against the Chicago White Sox in Comiskey Park. Soon after, Boston also called up pitcher Earl Wilson.

The final holdout to the integration of Major League Baseball had at last succumbed.

I left MCAD not long after, in 1961, to help the Kennedy administration establish the Peace Corps in Africa. I hoped that the changes I had helped to bring about for my home team would be long-lasting. But I knew that I could never again be a fan so long as Tom Yawkey, whom I regarded as a racist, remained the owner.

I never expected to be back in the midst of a Red Sox controversy nearly 60 years later, when Boston was holding hearings to consider renaming Yawkey Way back to its original, Jersey Street. I testified at all three hearings in favor of what I regard as Boston’s most progressive team ownership since Walter Brown led the Celtics.

My fellow African-Americans had in the past rarely felt at home in Fenway Park. During the time of the MCAD hearings, in 1959, it was derisively referred to by some as Aryan Acres. I think much has now changed in that regard. I expect that the occasional racial incidents caused by unruly fans will continue to be effectively dealt with by John Henry and his staff.

Now we can at last cheer without guilt for the Red Sox, as I — for so long — could not, when the hateful and hurtful curse of Tom Yawkey and his cronies still hung over the team.

Editors' note: Elijah "Pumpsie" Green died on July 17, 2019, the day this essay was published. He was 85.