Advertisement

Commentary

We cried for Tracy Chapman. And all our small towns and fast cars

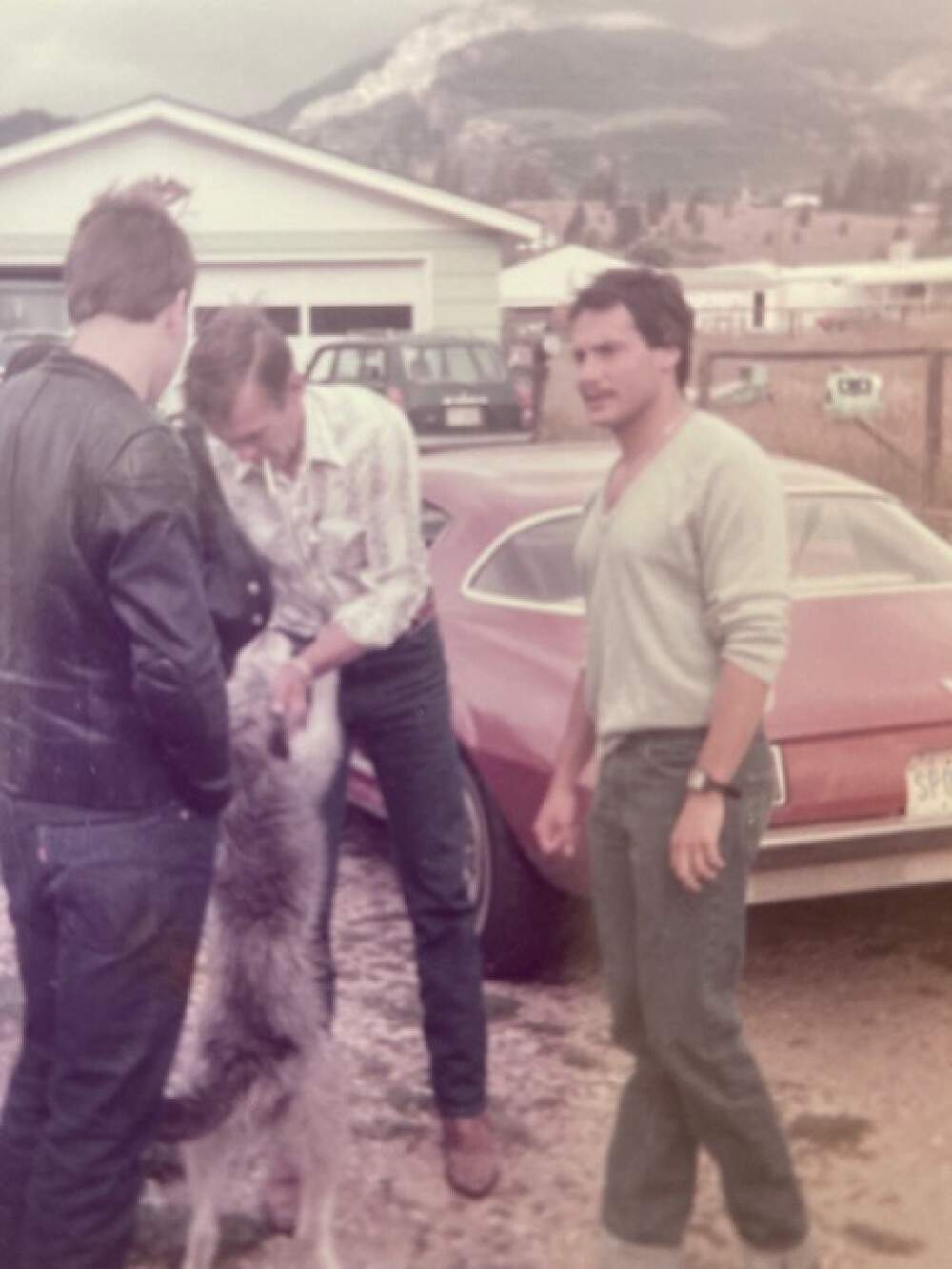

I did not come from a fast car family, but I came of age around fast car boys who drag raced on quarter-mile stretches of highway. Who souped-up Dodge Chargers and Plymouth Dusters and step-side pickups and their mama’s Chevy Malibu. Who dropped big old engines into muscle cars that were more putty than metal so they could cruise the drag on Saturday night. My dad was rightfully concerned about those boys and their cars and their intentions and their back seats and the dark canyons and lake roads around my hometown. Those fast cars had 8-track soundtracks, tapes like The Cars “Candy-O,” Foreigner “4” and AC/DC “Back In Black.” But, no song made me want to go fast more than Springsteen’s “Born to Run.”

Together we could break this trap

We’ll run ‘til we drop, baby, we’ll never go back.

My dad died in 1982 when I was 17 years old, hurling me into a years-long slide of grief-fueled bad decisions. I bought my own fast car in 1984, after totaling a wimpy Datsun 210. It was a red 1977 Camaro with a missing front grill and a sticky gas pedal, a car that begged me to get into trouble. I did wildly reckless, accelerated, intoxicated things while driving it. I often had to choose between buying food and buying gas, and remember putting a dollar’s worth in the tank. Forty years later, I see that car as an extension of my desperation. I was unmoored, broke and broken, pathetically lonely. I wanted my own Bruce, someone who would love me with all the madness in his soul, someone who could spring me from what felt like a death trap town. To save me from myself, I ended up selling that car and leaving Montana, alone.

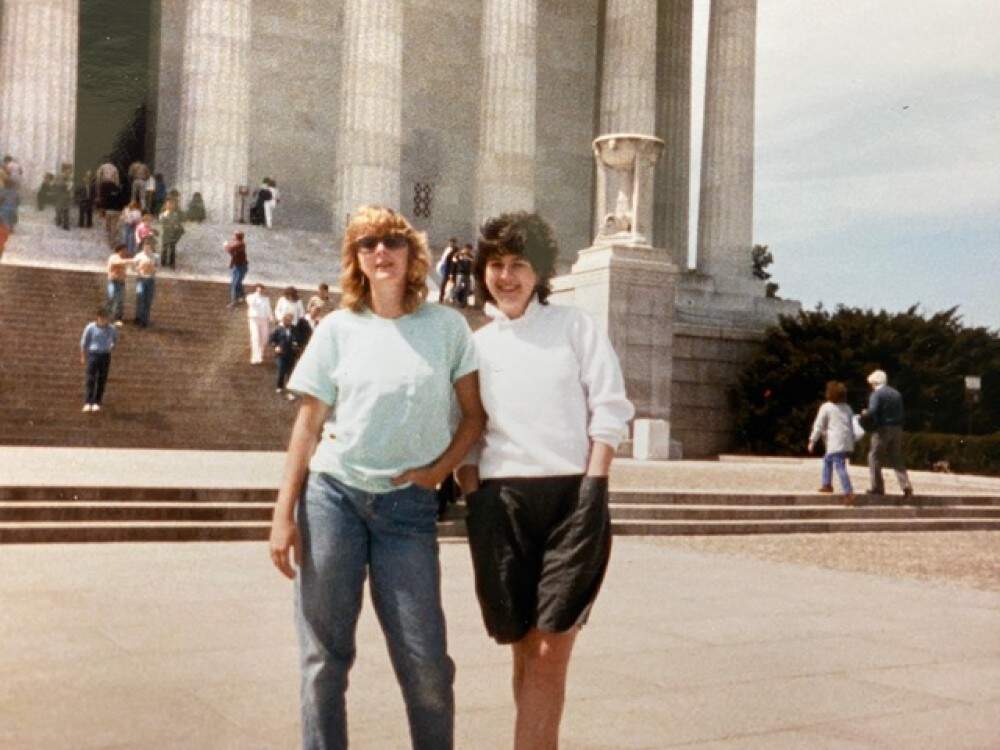

Fast forward to 1988. I was back in Montana, a recent college graduate, debt-ridden, living with my widowed mom in her rented apartment, working in a video store, trying to save a little bit of money so I could leave again. Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car” was an unlikely hit that summer. This queer Black storyteller with an acoustic guitar looped on pop radio along with flashy glam metal bands like Poison and Def Leppard. While the power bands demanded that someone pour sugar on them and declared they were only there for a good time, Tracy Chapman tapped into something fragile and raw and aching.

And I had a feeling that I belonged

And I had a feelin’ I could be someone, be someone.

Being back in Montana scared me. I didn’t want to be who I had been there, but past-me prowled that town like a sad dumb ghost shaking shackles I thought I’d thrown off.

Leave tonight or live and die this way.

Ah, and there was a boy. A fast car boy. He drove a two-toned Buick Skylark and lived over the garage at a fraternity house. He was charming and funny, a teddy bear along the lines of Jack Black whom everyone referred to by his last name: Fillner. But he mostly had eyes for my best friend, Wanda, who was dating one of his best friends. (Small towns.) When he gave me the time of day — or night — it made me think it might be the two of us. I was still looking for a ticket to anywhere.

Like “Born To Run,” like Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane” and Jason Isbell’s “White Beretta,” there is a sense that the young lovers in “Fast Car” are doomed. It’s wishful, not hopeful. Those kids don’t have a prayer; the deck is stacked against them. “Fast Car” didn’t lift me up. It made me feel like garbage in the way that only the best songs can. I suppose I wondered if Fillner might feel like garbage, too, and thought maybe the two of us could get out of there and try something different. It wasn’t love. But it was wishful thinking.

You’ve got a fast car

Is it fast enough that we could fly away?

If songs have a color, “Fast Car” is midnight blue: headlights on a highway, dim lamplight sparked with embers. “Fast Car” is walking a dark street to the bus after closing up the store. It’s restless nights spent daydreaming by moonlight. I have never once heard “Fast Car” and not thought of Fillner and everything that was wrapped up in that song for me. And because I was able to get out — on my own again, not with Fillner, as it turned out — “Fast Car” sometimes feels like an homage to what I’ve overcome, how I’ve had to forgive myself for being the screw-up that I was.

And then there’s Tracy Chapman herself. I saw her perform live once, in 1996, at the Alabama Theatre in Birmingham. By that time, I was more aware of myself as a white woman in a Black space and was humbled to have a seat I wasn’t sure I deserved to occupy. Like I did when she performed on Late Night with Seth Myers on Nov. 3, 2020, and like I did on Sunday watching the Grammys, as the camera panned from her hands on her guitar to that singular face I’ve admired most of my adult life, I burst into tears that night in Birmingham when the spotlight hit the stage and those first cords lifted everyone to their feet.

I didn’t know then that I would play her song, “The Promise,” on repeat in 1999, singing it aloud when I went into premature labor with my son, desperately begging him to wait until we were both ready. I didn’t know then that I would return to “Fast Car” in 2009, when I heard from Wanda that Fillner had died too soon. And I never imagined that all these years later, we’d still be talking about the same revolution, that the mere sight of Tracy Chapman performing her own song on the Grammys would reduce fans worldwide to tears.

On that stage, Luke Combs may have looked at Tracy with as much awe as any of us, but I don’t believe the tears shed that night were about him or about how white country fans embraced a song written by a queer Black woman, like finally the tables were starting to turn. We were crying for Tracy Chapman, for her iconic voice and enduring spirit. We knew all along that she would be someone. We were crying because it will always be “Fast Car” (Tracy’s version) for us.

Take your fast car, girl. Keep on driving.