Advertisement

Commentary

ICE's wanton use of solitary confinement defies even its own standards

In this election year, the debate about immigrants entering the U.S. has taken on renewed urgency. But it's also important to pay attention to the conditions faced by those already within U.S. borders.

As clinicians who provide medical care to immigrants and research conditions that affect immigrant health, we work at the intersection of medicine and policy. But the primary stakeholders in this debate, the ones often without a seat at the political table, are immigrants seeking relief.

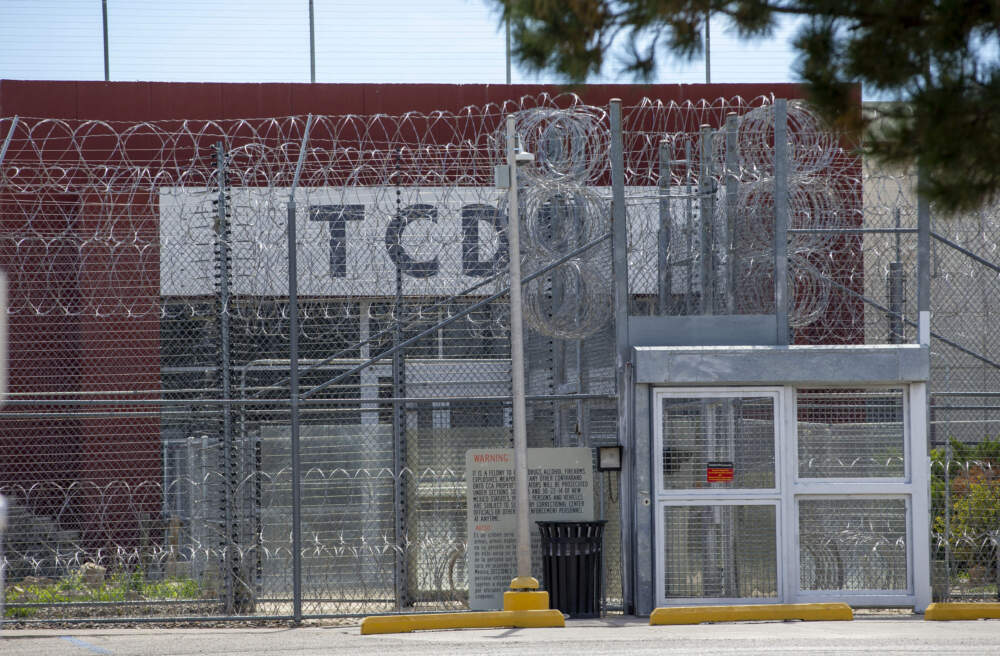

What happens behind the closed doors of immigration detention facilities is shrouded in secrecy, with information often incomplete and thus insufficient to inform needed change. As part of a team researching conditions within immigration detention centers, we were recently shocked to learn about ICE’s wanton use of solitary confinement for those in its custody. Approximately 38,000 people are currently detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) across a network of over 160 facilities.

Our findings resulted from a joint effort between researchers at Harvard Law School, Harvard Medical School and Physicians for Human Rights. We combined information from two sources: data we received from litigation of our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for internal government records about ICE’s solitary confinement use; and interviews with 26 formerly detained individuals who experienced solitary confinement in ICE detention facilities.

We found that ICE has used solitary confinement more than 14,000 times over the last five years alone. Detained immigrants spent an average of 27 days in solitary confinement, well beyond the 15 days that the U.N. considers torture. At least 42 people were held in solitary confinement by ICE for more than a year. Use of such prolonged solitary confinement is specifically prohibited by the U.N. Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules), and use of any solitary confinement — regardless of duration — should be “used only in exceptional cases as a last resort, for as short a time as possible.”

This extreme, dangerous and cruel abuse and overuse of solitary confinement is unfathomable, particularly as the majority of people held in immigration detention are detained administratively (not for criminal reasons but as a matter of immigration procedures). ICE’s own policies and care standards incorporate language similar to that laid out in the Mandela rules, but our report, and many others, show that these policies are not being followed and do not go far enough to protect those in their custody.

Many individuals we interviewed reported being placed in solitary confinement for arbitrary and often retaliatory reasons such as hunger strikes, suicidal ideation and as disciplinary action for minor infractions such as wearing the wrong clothes.

What does this look like? One of the people who we interviewed told us:

"Being in solitary, that is like a whole other level of playing with your mind. To bother you, to hurt you, to offend you, to make you feel like less than nothing. Even your biology changes, how you view the world changes ... your mind and your body break into little pieces."

This 50-year-old man detailed the verbal, physical, psychological and sexual abuse that he said he endured at the hands of ICE during the 90 days that he was in solitary confinement. His room was furnished only with a metal toilet, metal desk and metal bed. There was one window “about four fingers wide” facing the guards, the air conditioning was on 24 hours a day and he only received a blanket after repeated requests, he told us.

The lights were on from approximately 4 a.m. to 9 p.m., bedding was often stained and dirty, and the clothes he was issued were dirty and foul-smelling. While in solitary confinement, he experienced urinary retention necessitating the use of a catheter and a psychotic episode that led him to self-harm, all while having only sporadic access to medical care, he said.

The persons we interviewed described systemic delays and negligence in medical assessments, medication access and emergency care. ICE requires patients to be medically evaluated prior to placement in solitary confinement, yet less than half of our participants reported being screened. Access to medical care while in solitary confinement was inconsistent. One person reported waiting up to seven days to be evaluated for new lower-extremity swelling, potentially indicating a life-threatening infection or heart failure.

Mental health care was also deficient while in solitary confinement, with just under half of interviewees waiting longer than one month to be seen or worse — not being seen at all. When mental health visits did occur, study participants described them as cursory check-ins, done through the window of the cell door without the ability to maintain privacy or form a therapeutic relationship.

People reported that solitary confinement generated new mental health concerns. One person said, “I ended up … talking to myself. I thought about suicide.” Another said that he felt so crazy that he “kept banging my head on the door.”

All of this violates ICE’s own policies and guidance — that people with mental health conditions should seldom, if at all, be placed in solitary confinement. Perversely, however, the FOIA data showed that people with mental health conditions were disproportionately subjected to solitary confinement, and that the proportion of people with mental health conditions being placed in solitary confinement was actually increasing annually. In 2023, over 56% of people in solitary confinement had an existing mental illness.

Finally, individuals in this study also corroborated what previous interviewees had told us in a study of ICE detention centers we undertook at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic: Solitary confinement and medical isolation are being conflated. Medical isolation in medical settings never looks like solitary confinement, nor should it. ICE’s directives indeed state that medical isolation is one acceptable form of administrative segregation, but only as a measure of last resort and if other isolation facilities are not available.

At least 42 people were held in solitary confinement by ICE for more than a year.

As medical professionals, we are taught to see the humanity of our patients and to help repair their bodies and minds. We see first-hand the truism of famed 19th-century physician Rudolph Virchow’s aphorism: “Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing more than medicine on a large scale.” We are also taught to investigate the contexts in which our patients live and how those conditions may impact their health. It has long been known that solitary confinement is severely detrimental to one’s physical and mental health.

We cannot sit idly by and allow tens of thousands more to suffer and develop debilitating mental and physical conditions as a result of this inhuman practice. In line with our oath to do no harm and to see the dignity in those who are coming to us for help, we call on the Biden administration and ICE to immediately end its use of solitary confinement.

Katie Peeler is a pediatric critical care physician in the division of medical critical care at Boston Children's Hospital and on faculty at Harvard Medical School and medical expert for Physicians for Human Rights. Anand Chukka, Brian Benítez and Natalie Sadlak are medical students at Harvard Medical School.