Advertisement

Commentary

After my sister died, I found refuge in my running sneakers

Editor's note: This writing contains references to suicide, suicide attempts and completion, suicidal ideation, and suicide coercion. Please use discretion while reading.

I often think it isn’t a coincidence that so many endurance athletes come to running after experiencing something awful. Addiction. Cancer. Loss. Trauma. Everyone seems to be running for something, or from something, or through it.

My sister’s death was what led me to my running sneakers. And while most people have heard of a “runner’s high,” or know that physical exercise releases endorphins and supports our mental health in an almost medicinal way, that’s not the story I’m telling.

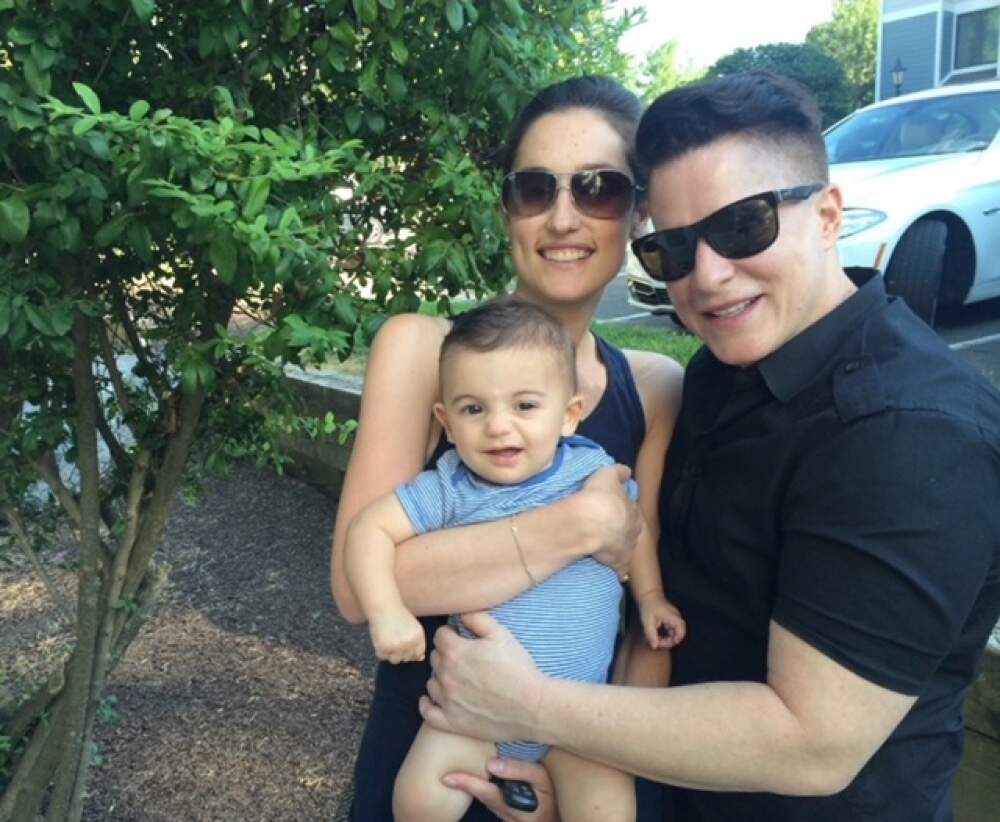

I started running when I was in college, but it was too hard and I hated it. For years, I ran to stay fit and counted down the minutes until my runs were finished. But my relationship with running changed when, almost 20 years later, Liza died by suicide. I was sitting on the brown leather sofa in my living room late on a Sunday night, when an NYPD detective called me with the news, and the air dropped out of my chest. It broke me apart in a way that the pieces would not fit back together the same way they once did.

I’ve lost other loved ones due to illness, old age or both, but because it was suicide, Liza’s was an out-of-order death that my mind couldn’t make sense of. I experienced a uniquely torturous combination of grief, post-traumatic responses like panic and intrusive thoughts and endless unanswerable questions. The guilt and stigma associated with suicide made it especially lonely, too. With such a complicated death, it is no wonder that my grief was complicated too.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, complicated grief, also known as pervasive grief disorder:

requires the occurrence of a persistent and pervasive grief response characterized by persistent longing or yearning and/or preoccupation with the deceased accompanied by at least 3 of 8 additional symptoms that include disbelief, intense emotional pain, feeling of identity confusion, avoidance of reminders of the loss, feelings of numbness, intense loneliness, meaninglessness or difficulty engaging in ongoing life.

I had them all.

In the days, weeks, and months after Liza died, I dreamed of becoming a hermit. Everything felt like irritating noise, and isolating in my darkened, quiet bedroom seemed like the only way to cope. But with a career and a family that included two children under five, I couldn’t. If I had told my husband, “I’m going to lock myself in a dark bedroom for a few days. You’re on kid duty,” he would have worried. But, “Hey, I’m going for a run. Do you have the kids?” No red flags raised. So instead of hiding under the covers, I learned to hide inside a fresh pair of Size 8 Brooks Adrenaline running sneakers — navy with gold accents.

When I was running, I could block everything out and no one could get to me. I didn’t have to navigate painful conversations where people did or did not mention Liza. I couldn’t read work emails, and my kids couldn’t pester me for snacks. Running was proof that somehow, I was still here, because with a warm body, lungs ballooned with oxygen, heart pounding and blood coursing through my veins, it was the exact opposite of being dead.

When the scariest thing possible, the thing I dreaded, actually happened, part of what it left behind was fearlessness, and a mind much more insistent than the body, one that said keep going even when my body objected.

After one or two miles, my feet would settle into a rhythm. My watch would clock two miles, then three, and then four, with no temptation to stop. I was running through an imaginary wall and kept going until I released enough endorphins to hurl myself into the next part of the day — or until my body was simply exhausted. Running can hurt, and when it did, I welcomed the pain in some weird, subversive way. There were plenty of dangerous vices I wasn’t turning to, and this physical discomfort felt right, like an emotional release valve I needed every day.

With such an uptick in miles I developed greater endurance, and though still not fast, I became faster than ever before. My family and friends started to notice. They congratulated me. To them, I was doing well, great even. I presented as strong and healthy. But they could not see the way I depended on the isolation of running to cope with the mounting anxiety and depression that came with Liza’s death. I could not see it clearly then either.

It has been more than three years since Liza died and my grief is not leaving, but on most days, it is not as sharp or as complicated as it used to be. Whenever I see a talented runner — one with a steady torso and legs like wheels — I cannot help but wonder if something happened to them, too. Maybe they just like running, or maybe they’re like me.

I am not an endurance athlete, and while I’ve fallen back into a casual, even sporadic, running practice, odds are that life has more grenades to throw at me. When they land, I know that, at least for a while, there will be a safe place to hide inside my running sneakers.

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal ideation, please call the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or text HOME to 741741.