Advertisement

Commentary

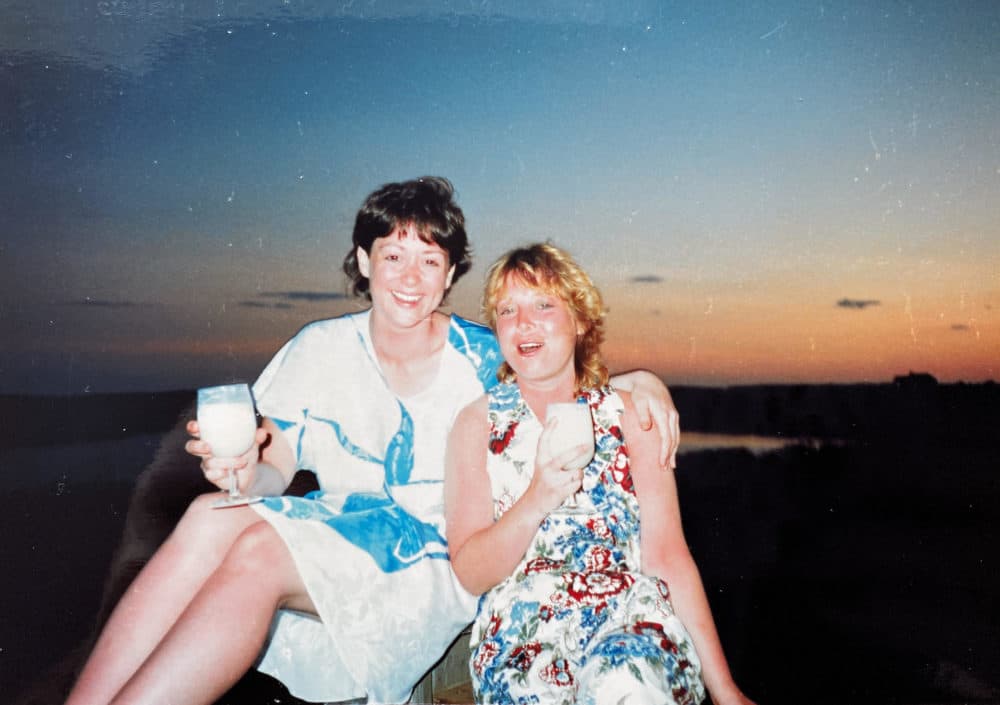

My sister’s death was hard enough. The silence afterwards was unbearable

It’s been seven years since my sister died, and in ordinary moments, I am still blindsided by the intensity of my unresolved grief. Recently, a three-sentence email sent me spiraling.

Not sure if u remember me but I was Cheryl’s college roommate. I’m trying to get in touch with her for a reunion. Any chance u can provide me with her contact info?

I knew within seconds of reading the message, I would tell her roommate the truth.

I’m afraid I have upsetting news. She passed away in the summer of 2015. She struggled with mental health issues, and sadly, died by suicide.

All grief is difficult. When I was a high school sophomore and my sister was a freshman in college, our father died of a sudden cardiac event at 47. No remarkable history. No warning. One day he was healthy and vibrant, the next day, gone. Each of us in our family of five survivors struggled in our own way, but in the years afterward it became clear that my sister’s capacity for healing was complicated by mental health issues.

Some grief is impossible. Death by suicide remains stigmatized, and because of this, I’ve been told — implicitly and explicitly — to keep that grief hidden. I’ve been stunned by the absence of compassion after a loss deemed undiscussable. Seven years later, some extended family members still have never acknowledged my sister’s passing. To me, this feels like they are erasing her existence.

When people become uncomfortable at any mention of my sister ... I feel excluded from the mourning process.

When people become uncomfortable at any mention of my sister, or they change the subject entirely, I feel excluded from the mourning process. Experts call this disenfranchised grief, as if only some lives are worth public mourning. It’s true that the manner of my sister’s death is disturbing, the details upsetting. But usually, I don't want to talk about how she died.

Sometimes I want to talk about the good days. For decades, my sister and I were central players in each other’s lives. We spoke every day. Had many of the same friends. We lived next door to each other in Boston.

Rarely do I have the chance to reminisce about how Cheryl turned me on to music. On a trip to Montreal, we fell in love with Offenbach and sang "Chu un Rocker" at the top of our lungs wherever we went. I want to remember all the fun we had in her New York apartment by the East River, and the afternoon in the fall of 1981 when we walked to Central Park to see Simon & Garfunkel, reunited for their one-night-only concert.

Advertisement

Cheryl was an aspiring writer. Everywhere she lived, except for her last apartment, her home was a library. She arranged brightly colored comfy chairs in front of floor-to-ceiling shelves filled with hardcovers of Plath, Woolf and Nin. She was a talent, and I felt pride when she’d ask me to read a new short story. My sister was pretty and spontaneous, with a killer humor that required your mind to be active and engaged because sometimes the joke was on you.

The cause of death should not render a loss any less significant ...

As much as I loved her, my grief is complicated by the ways her mental health impacted my own. No matter how many times I raced to her apartment after she threatened to hurt herself, or tried to console her after a painful breakup, a lost job, or a fractured friendship, I was no match for her all-consuming illness. Each time she "fired" her therapist, I felt desperate to persuade her to try someone new. I assured her there had to be a better fit out there. Someone more capable than I, to give her a respite from the weight of her troubles.

In the years since my sister’s death, I’ve come to know that no benefit comes from what poet John O’Donohue calls “the hungry altar/Of regret and anger and guilt.” Instead, I’ve found healing in the belief that every person is grievable. When I’m asked about my sister, I tell the truth about her life and her death, and my heartache. If I’m working to be comfortable with the totality of it, maybe you can too.

And I mourn with and for other people who have loved someone who died by suicide, overdose, violence, or any of the other losses society tells us ought to be relegated to the shadows. The cause of death should not render a loss any less significant nor should it add any more pain to living with it.

When I try to see myself in other people’s sadness, something profound happens. When I express empathy for their experience, I honor my own. By connecting with others, I make space for the lovely memories I have of my sister, and for the sad and bitter ones too. There, finally, I’m entitled to grieve.

Editor’s note: You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) and the Samaritans Statewide Hotline (call or text) at 1-877-870-HOPE (4673). Call2Talk can be accessed by calling Massachusetts 211 or 508-532-2255 (or text c2t to 741741).