Advertisement

Losing To Lyme

As Ticks And Lyme Disease Spread, Prevention Efforts Limited To 'Shoestring'

Resume

Part of our Losing to Lyme series

Last August, an 81-year-old man from East Falmouth, Massachusetts, died of a very rare virus called Powassan, a tick-borne infection that can lead to paralysis and death. Otherwise healthy and active, he was killed by a tick.

A few months later, Falmouth's assistant health agent, Mallory Langler, was speaking to the man's widow, and it dawned on her that the town’s efforts to stop ticks don't extend beyond education. "I can give you a pamphlet,” she says. "That’s not a whole lot when your husband just passed away from a tick-borne illness."

Despite more than a decade of widely praised education efforts on tiny budgets, cases of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases in Barnstable County remain among the highest per capita in the country.

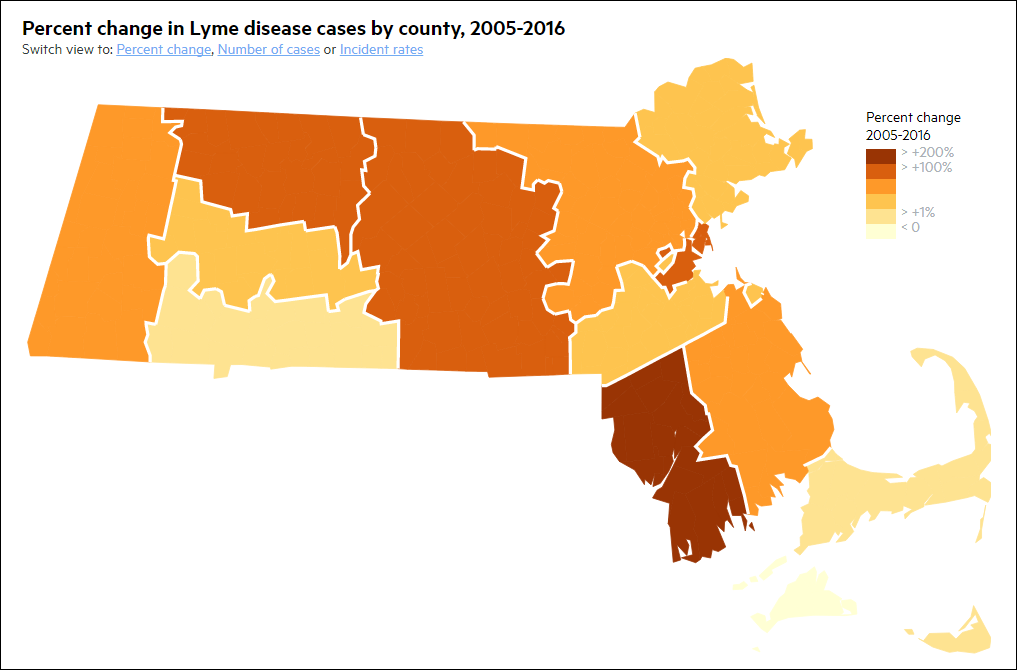

In other counties across Massachusetts over the last decade, Lyme and other tick-borne diseases have grown inexorably as a public health risk — spurred by growing suburban habitats, rising deer numbers and climate change.

A WBUR analysis of state Department of Public Health data finds that Lyme risk remains highest on the Cape and Islands, but all of eastern Massachusetts is now at high risk and the disease has spread westward as well. While local rates fluctuate slightly due to droughts and other factors, over time the overall trend goes in one direction: up.

The problem has also become year-round: Fifteen years ago, winter risk was thought to be nearly nil. No longer. And the danger goes beyond Lyme — to Powassan and other diseases that can have far more severe immediate effects.

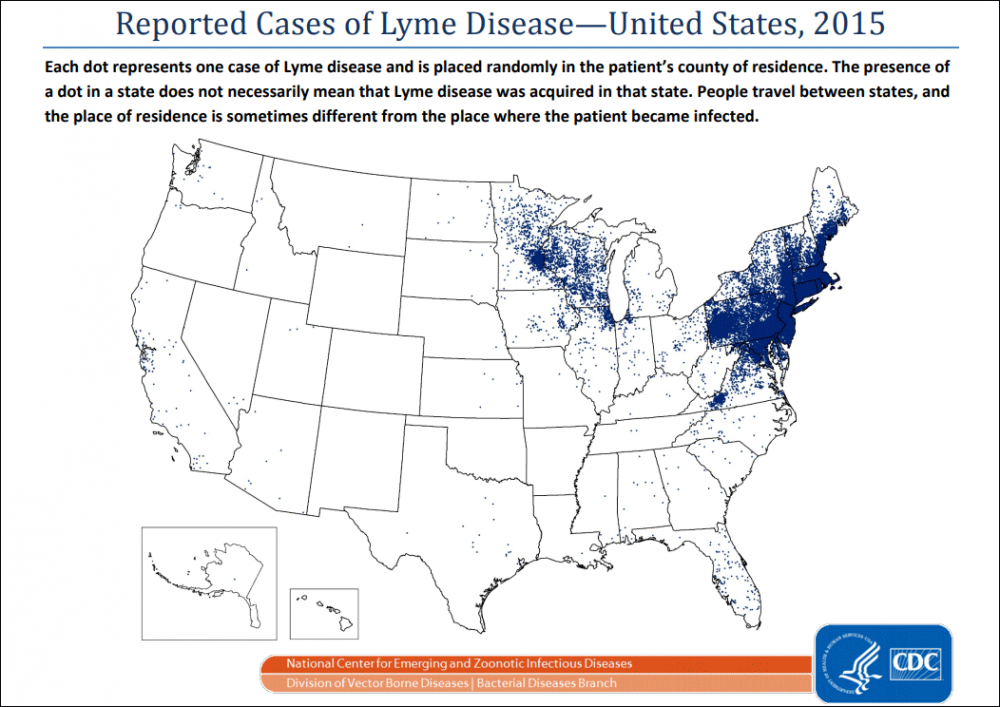

Nationally, too, more counties have high loads of Lyme disease, which infects an estimated 300,000 or more Americans each year. Once confined to New England and the upper Midwest, Lyme disease-causing ticks have spread to half of the counties in the U.S. Now, ecologists are predicting that 2017 will be a bumper year for ticks and the illnesses they spread.

Dr. Patrick Cahill, an infectious disease specialist at Cape Cod Healthcare, says it’s not clear on the ground whether this year is bringing an exponential rise in tick-related illness, but "it’s certainly noticeably more frequent from year to year."

"Over the course of several years," he adds, "we’re seeing more than we used to, and that’s related to the increasing distribution of the tick that transmits these diseases, and, correlated with that, the diseases themselves.”

So how are we fighting back? Mainly, as in Falmouth, with education about preventing tick bites.

And why do we seem to be losing? Because, as some towns in Massachusetts and beyond are coming to realize, education clearly helps -- but, equally clearly, it isn’t enough to stem the tide of disease as the ticks spread.

Even with all the will in the world.

'One Bite Can Change Your Life'

Entomologist Larry Dapsis gives his "One bite can change your life" talk about 70 times a year, by his count.

At a recent talk at a Mass Audubon wildlife sanctuary in Wellfleet, he puts up a picture of the smiling Dalai Lama on the screen with the quotation, "I love everything in the world ... except for ticks."

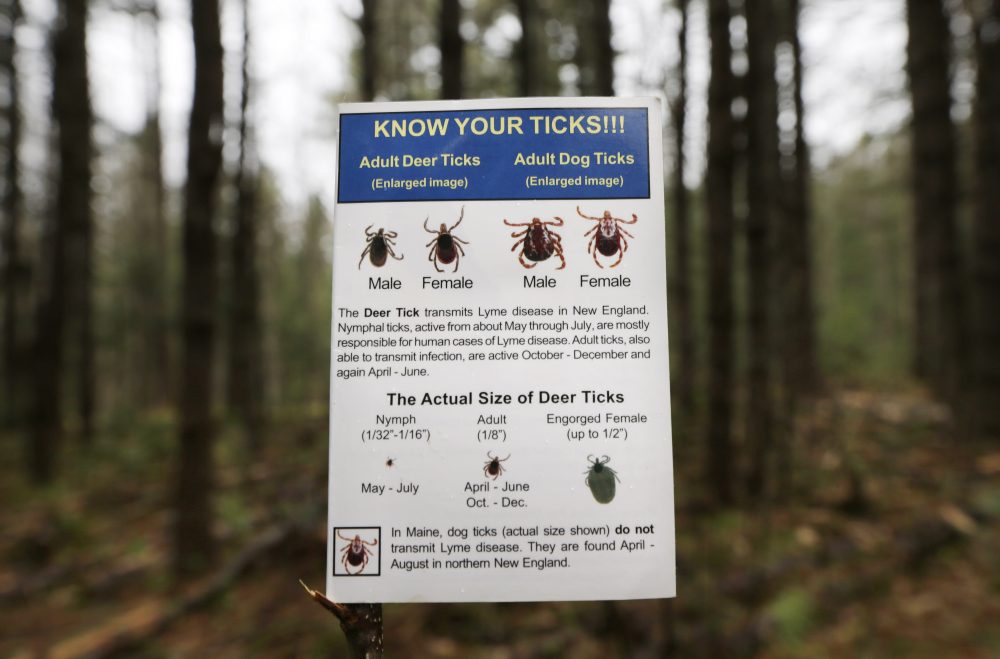

"Even the Dalai Lama, lover of every form of life on the planet, doesn’t like them,” he says, drawing chuckles from the crowd. Then he launches into ticks’ biology, their life cycle, the diseases they carry, and how to prevent them. (His recipe: Protect yourself, with tick checks and repellents; protect your pets, with collars and topical medications that stop ticks; and protect your yard, by getting it sprayed against ticks.)

As the tick project coordinator for Barnstable County, Dapsis takes his show on the road to anywhere in the county he is invited. At times, he even takes it to the grocery store, where he wears a T-shirt with a large tick on it because it occasionally triggers a chance to "do a workshop even at aisle seven in Hannaford."

At 61, Dapsis has difficulty standing for long periods of time due to complications from diabetes — but he’s a former hockey goalie, so he knows how to skate through pain, and he doesn’t let it slow him down. After his presentation at the wildlife sanctuary, he went to drag for ticks at a state park he’s nicknamed "tick nirvana."

“We’re not building nuclear submarines, but we are making progress on a shoestring," he says of Barnstable’s education efforts.

Shoestring is right. Aside from his personal dedication and drive, the county has few resources for educating people about Lyme and ticks -- mainly, a pair of $20,000 to $30,000 grants from Cape Cod Healthcare’s Community Benefits program over the last three years.

Along with those grants and Dapsis’ salary, the Cape Cod Cooperative Extension spends a little over $10,000 yearly on pamphlets and workshops, educating physicians and tick testing, according to Michael Maguire, the cooperative's director.

In 2013, a Lyme commission created by the Massachusetts Legislature recommended $300,000 of state funding be allocated to emulate Barnstable’s educational initiatives elsewhere, seeing a chance for high public health impact at a relatively low price.

But Massachusetts still allocates no money specifically for Lyme disease prevention. And the state receives just $40,000 a year from the federal government to support disease surveillance and education.

"There probably isn’t anybody in Massachusetts who doesn’t know somebody who has been affected by Lyme."

state Rep. David Linsky

State public health officials do work extensively on Lyme and other tick-borne diseases, but that work is just not budgeted separately, says state Rep. David Linsky of Natick, who chaired the Lyme commission.

But that means that for Massachusetts to dedicate money to Lyme, it must pull resources from other pressing health issues, like tobacco control or addressing the opiate crisis.

“The state Department of Public Health, quite frankly, has probably been underfunded for a number of years and they have a lot of responsibilities,” Rep. Linsky says. “We need to do a better job of making sure they can meet all of their other important responsibilities and still have something left over for Lyme.”

Some public health experts suggest that since the state has mosquito control districts and towns contribute $11 million a year to mosquito spraying and surveillance, it should expand their work to tick surveillance, like California's mosquito and vector control districts.

But, unless towns or the state can come up with more money, that appears unlikely at this point.

Tufts professor Sam Telford, a Lyme specialist, also happens to be one of five commissioners for the Central Massachusetts Mosquito Control Project. While he joined because he hoped to expand their work to ticks, “I’ve given up on that prospect,” he says, because they’re short-staffed and already overloaded with the tasks for mosquito control.

“They have a lot on their plate,” he says.

Last year, Rep. Linsky spearheaded a bill requiring insurance companies to cover long-term antibiotics for Lyme, which passed over Gov. Charlie Baker’s veto. Otherwise, most of the 2013 commission's recommendations for fighting Lyme have not come to pass. Its main result appears to be better coordination.

“What I’m trying to do is to have the state Department of Public Health be a central repository of best practices -- the best types of pamphlets, the best type of science educational training materials,” Rep. Linsky says. “We are encouraging the state Department of Public Health to put more resources into Lyme and they have been doing that."

Federally, Lyme-related bills are occasionally introduced in Congress, but nothing has passed that would change the landscape for tick-borne diseases.

Why Not A 'Neighborhood Tick Watch'?

For anyone who has seen the effects of Lyme and other tick-borne diseases close up and come to fear them, it can be baffling that more is not being done — that efforts to turn the tide against ticks are limited to shoestrings.

“There probably isn’t anybody in Massachusetts who doesn’t know somebody who has been affected by Lyme,” Rep. Linsky says. “There is one degree of separation.”

So what is to be done?

On the Lyme front lines in Falmouth, the recent death from Powassan helped galvanize brainstorming in the health department on ways to address tick-borne disease by doing more than just education.

“So far, we kind of do things passively,” said Falmouth Health Agent David Carignan, who has had both Lyme and another tick-borne infection, ehrlichiosis. “We offer information, we make recommendations, we talk a lot, we try to increase the awareness of the public.”

He connects the rising tick numbers to patterns of land use in Falmouth: On what was once treeless farmland, trees have grown and now our suburbs are among them, providing more protected recreational space where ticks flourish and people come to garden, hike and walk dogs. We think of it as natural habitat, but even before Columbus, the indigenous people of Massachusetts were clearing brush and using fire to clear paths for easier hunting.

Now, he says, “what we would like to do is begin a conversation about where we go from here. There’s a chance to start to get it right if we start to think a little differently."

So, for example, because ticks thrive at the edges of forests, Falmouth has begun working with volunteers to widen hiking paths, clearing them of underbrush, he says. The town is looking into what it would take to spray trails to keep the ticks away.

What they’re talking about — trying to control the tick population on the ground — is known as “integrated pest management,” a full-court press of the type already used statewide to control mosquitoes.

Catherine Brown, the Massachusetts public health veterinarian, applauds efforts by towns like Falmouth to take the lead in this new way of approaching tick-borne diseases.

“It’s one of the reasons I’m so excited about the approach that Falmouth is taking," she says. "Because -- I know this is going to sound a little trite -- but it takes a village. It’s going to take groups of stakeholders working on different levels, [and] the integrated pest management level is an important component."

"We have neighborhood crime watches. Why don't we have a neighborhood Lyme watch?"

Ben Beard, CDC

An integrated attack on ticks could include multiple environmental techniques, she says, although some still lack enough evidence on how well they work, and more studies need to be done. Current methods under investigation include:

- Reducing tick habitats by eliminating leaf litter, wood piles and other areas where ticks hide.

- Managing deer populations at sustainable levels.

- Reducing small rodent populations by removing food sources like bird feeders and favorite habitats like stone walls.

- Using techniques to apply tick repellents to wild animals, including deer and small rodents.

- Spraying yard and forest edges with a tick-killing product that has some residual effect.

- Treatments and vaccines aimed at stopping the infection in mice.

“Add in awareness, personal prevention,” Brown says. “It is going to take a community-level approach, I think, to really start to have any type of an impact.”

That would include residents working together to fight ticks. As Ben Beard, chief of the bacterial disease branch in the CDC’s Division of Vector-Borne Disease, puts it, “We have neighborhood crime watches. Why don’t we have a neighborhood tick watch?”

And it will take resources, which even Falmouth does not have at this point. Town budgets are small and staff is always short.

Even if well-funded, experts agree that education alone is unlikely to stem the rise of tick-borne disease. Studies suggest that people tend to follow prevention recommendations sporadically, and less and less over time. Parents are often reluctant to expose their children to chemicals that ward off ticks, and quickly discover the impracticality of checking for ticks after every outdoor activity.

It remains to be seen whether the spread of a new, potentially fatal tick-borne virus will spur new efforts — and new resources — to fight ticks.

The Powassan virus remains extremely rare — there were only two fatal cases in the state last year — but it’s here. Cahill, of Cape Cod Healthcare, says he’s seen two confirmed cases of it and four suspected cases. It tends to involve quickly spreading paralysis.

"It is a scary disease to witness," he says, "because, similar to the other viral encephalitis causes, it can progress very quickly, and ultimately lead to death."

He expects tick-borne infections to continue to rise, barring the sort of major winter deep freeze that hasn't hit in recent years, or some other major natural change.

"We're going to continue to see more and more of these infections," he says, "related to increasing tick distribution, along with climate change."

David Scales MD, Ph.D., is a physician at Cambridge Health Alliance and Harvard Medical School. He can be found on Twitter @davidascales.

This segment aired on July 17, 2017.