Advertisement

People With ALS Living Longer, More Independent Lives At High-Tech Chelsea Home

Just outside Boston, there's a place where people who've been diagnosed with one of the most cruel and debilitating diseases are living longer and more meaningful lives than ever thought possible.

The disease is Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), or Lou Gehrig's disease. And the place is the Leonard Florence Center for Living. It's a contemporary brick building along a hillside in Chelsea.

Inside, something revolutionary is happening. And it's all thanks to two men who make an unlikely pair.

A Mission To Give People 'A Better Quality Of Life'

First, there's Barry Berman. He's a gentle, avuncular 64 year old, who works in a sweater and tie and loves what he does. He runs the center — a skilled nursing facility.

"I think I have the best job in the world, because I go to work every day and my mission is just to try to make people have a better quality of life," Berman says.

The other half of the pair is 49-year-old Steve Saling. He's a self-proclaimed rebel, with shoulder-length dirty blonde hair and a penchant for T-shirts and Birkenstock sandals. He has ALS and lives at the center.

"I was told my life expectancy was three to five years. I've always had a problem with authority. I don't like to accept what makes no sense to me," Saling said, speaking through a computer.

That was 12 years ago. Now, Saling's arms and legs are paralyzed. He communicates through a computer because ALS took away his voice. He uses a tiny mouse — a metallic circle on the bridge of his glasses — to point at words and letters scrolling rapid-fire on the screen of the computer, which is mounted to his wheelchair. It takes a few minutes for him to piece together a sentence.

Saling is blunt about his condition: "I am completely dependent on others and will be for the rest of my life. I require help if I want to have my position changed at night. I cannot scratch my head or rub my eyes, even when an eyelash gets in there."

Saling used to work as a landscape architect. In fact, he specialized in making public spaces accessible for the disabled — including the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston.

When he was diagnosed with ALS, he had a newborn son.

Advertisement

Saling had always liked to noodle around with technology; he was a real "Inspector Gadget," he says. That passion, along with his need for long-term nursing care and Barry Berman's vision of nursing care, converged.

Berman recalls the two were introduced at an ALS conference in Boston: "From [that] point on, I do believe a higher power just took over and made this happen."

Berman was on a mission to re-conceptualize the design of a traditional nursing home, to make it more like a residence that also happens to have state-of-the-art nursing care. He envisioned private bedrooms opening up to a communal living area. And it would be non-profit. Berman says Saling was all about customizing technology for people with disabilities.

"Steve single-handedly designed a household where he would live the rest of his life and have all the technology and the care that he would need so he could lead an independent life."

Barry Berman

"Steve single-handedly designed a household where he would live the rest of his life and have all the technology and the care that he would need so he could lead an independent life," Berman says.

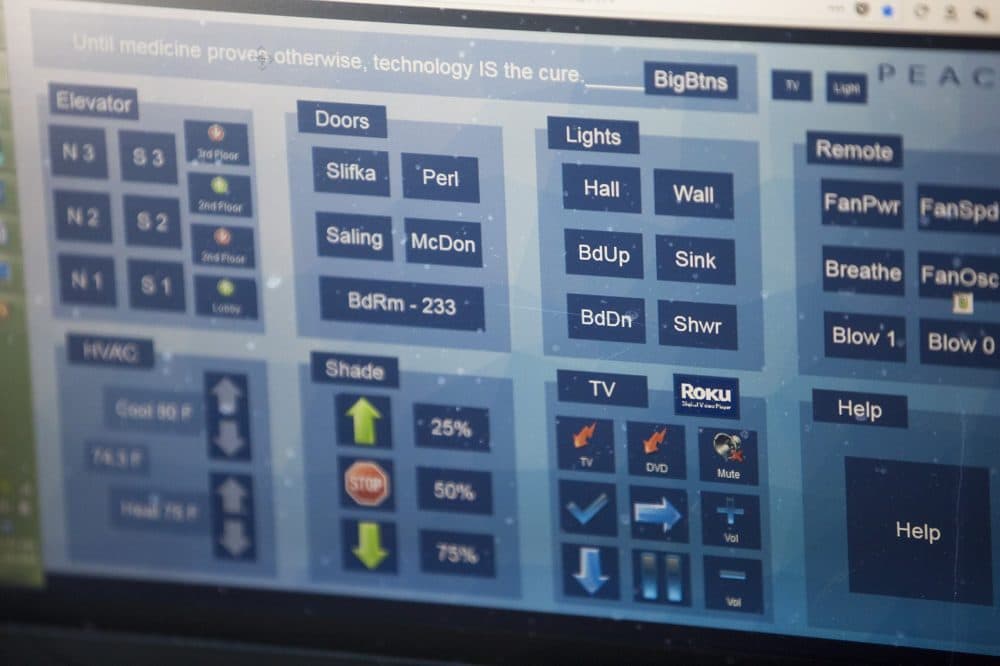

The place is wired with computers that help residents do things their hands can't do. Saling says the individual components of the system are off-the-shelf stuff — and just need Wi-Fi and a browser. But he worked with a home-automation software company to tailor the system for people with disabilities.

'A Level Of Independence Previously Unheard Of'

Saling leads us on a tour from his wheelchair, taking us first to the facility's first-floor bakery and cafe.

"We have a full-time baker who makes amazing homemade fresh pastry daily. There's a 15-foot screen that drops from the ceiling for movies and events, like the Super Bowl," he says. Saling previously created sound files he can re-use to lead people on tours of the facility.

There's a kosher deli next door. And there's a chapel with stained-glass windows down the hall. Farther down, there's a day spa, with hair stylists, manicurists and massage therapists.

Saling moves his head ever so slightly to aim at an infrared dot on the wall that lets him call for the elevator. Residents who can’t move their heads can send commands with even small eye movements.

We exit the elevator into a sunny lobby. This floor is called the "Steve Saling ALS Residence." It's one of two ALS floors. Each has 10 beds.

"By looking, you would never know that this is a nursing home ..."

Steve Saling

The outside wall of the entrance has wood siding, to look like a house. There is a mailbox and a doorbell. There's no need right now to ring the doorbell, though. Saling opens the door by pointing his glasses-mounted mouse at his computer.

"Welcome to my home. By looking, you would never know that this is a nursing home ... We are in the living room now complete with an electric fireplace," he says.

There's a pristine kitchen and a long woodblock dining table. Residents create their own menus — even if they're on a feeding tube, as Saling is.

When he wants a drink — Saling's a bourbon man — he takes a shot of Maker's Mark through the tube.

Saling leads us into his room.

"I can control the lights, the window shade, the thermostat, the TV and home theater, and any electrical device, like my fan," he explains.

He turns on the TV to ESPN. On a shelf, there are dozens of books and CDs, including his favorite Stones album, "Sticky Fingers."

The walls are raspberry-colored. His mother painted them. They're covered with framed family and vacation photos, along with a huge surrealistic picture Saling painted.

There's also a private bathroom with a ceiling lift that staff use to carry Saling from his wheelchair to the shower and toilet.

"I even have a remote-controlled bidet to wash and dry my bum so that I maintain that independence," Saling says. "All of this technology means that I have a level of independence previously unheard of for people like me."

CEO Barry Berman says he wants residents to be treated with dignity.

"Many of our ALS residents, when they have been admitted here, hadn't experienced a shower in several years," Berman says. "We take our ventilator residents in the shower, and people have showers. That's human dignity that every human being should have warm water cascading over their body. That's not innovative."

He explains that it takes four aides to give someone with a ventilator a shower, because the equipment can't get wet.

Living Beyond Prognoses

Like Saling, many of the residents here with ALS have lived well beyond their prognoses. Berman believes that's at least partly because of the quality of the care.

He says there are two or three times as many nurses and aides on duty than in a typical nursing home. And they know the residents so well, they can immediately spot an infection and treat it — or suction out a resident's lungs — which can keep the resident from having to go to the emergency room.

"Because of that, we sometimes go six months — we could go a year — without an empty bed," Berman explains. "And when you average two or three calls a week ... desperate calls from people around the country and around the world, it's really heartbreaking. We weren't prepared for people living as long as they're living here."

Berman recalls once finding an employee who handles admissions crying.

"And I said, 'What's the matter? Did something happen?' She said, 'I just can't take all these ALS calls.' "

It costs the center $50,000 per year to take care of each resident with ALS; that's after Medicaid, and nearly all of the residents are on Medicaid.

"... We sometimes go six months -- we could go a year -- without an empty bed."

Barry Berman

Berman's goal is to replicate the home — but he says that won't happen without more philanthropy.

Steve Saling can't wait for the day when everyone living with disabilities has access to this kind of technology and care. For now, he savors what he and Berman have created.

"The most satisfying part of my day would have to be towards the end of the day, especially when I have a particularly productive day, when I can medicate with cannabis, kick my feet up and watch a good movie in my home theater," Saling reflects. "It is relaxing and very satisfying."

He says life is good.

This article was originally published on May 03, 2018.

This segment aired on May 3, 2018.