Advertisement

Atul Gawande: Mass. Is Seeing 'First Signs Of Real Change' In End-Of-Life Planning

Resume

Three years into a campaign to shift attitudes about end-of-life planning in Massachusetts and to make sure residents get the care they want, there are a few signs of improvement — and lots of room for more.

WBUR's Bob Oakes spoke to Dr. Atul Gawande -- author of "Being Mortal" and co-chair of the Massachusetts Coalition for Serious Illness Care -- about the initiative his book helped launch and the third annual end-of-life care survey, conducted by UMass Medical School. This transcript has been edited.

Bob Oakes: You’ve been writing about the way Americans approach dying for many years now. What do you see here from Massachusetts residents that you find encouraging?

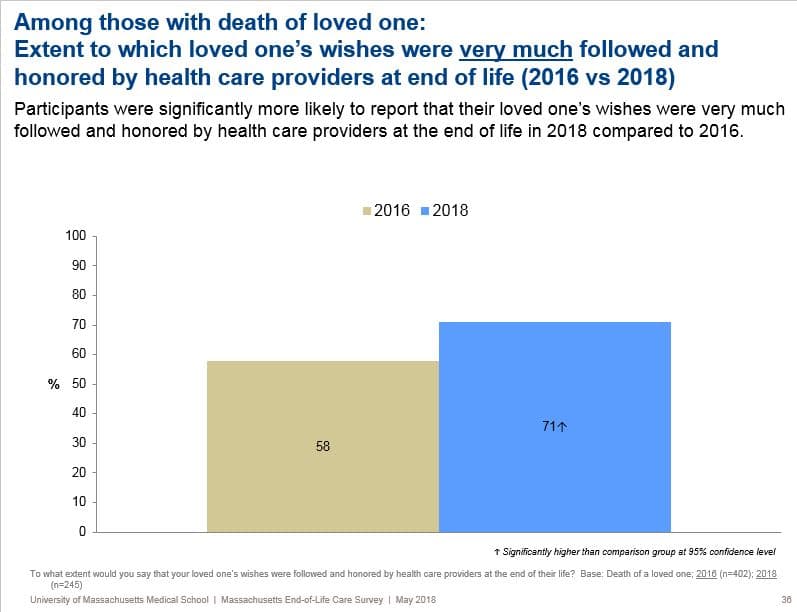

Dr. Atul Gawande: We're seeing the first signs of real change. We found [with this latest survey] that there were significantly more respondents who said that their dying loved one's care wishes were followed and honored by care providers. That was up from 58 percent in 2016 to 71 percent this year. That's a big leap.

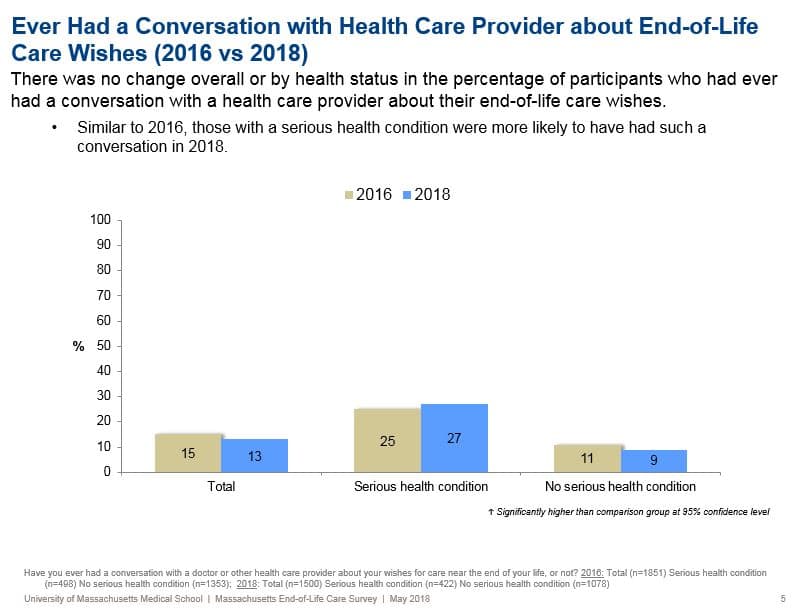

It's also a little hard to understand how things are improving, because as I read it, only 13 percent of people say they've actually discussed end-of-life wishes with a doctor or nurse.

Yes, there's still a very broad sense that the underlying indicators — Have people chosen a health care agent who can speak for them when they can't? Are they talking to their doctors about the wishes for their care if they have a serious illness that could lead to impairment or the end of life? — those numbers are still very low. Even people who are currently living with a serious illness, only about a quarter had talked to their doctor about what to do if their health becomes worse.

I also found it interesting that when those conversations do take place, it's the patients or the family members who start them, 60 percent of the time. Do you think that means that doctors are still uncomfortable or too busy to have these conversations, or is there something else going on?

You put your finger on it. I think it's a bad sign for us in the medical profession that patients have so much better care when they have the conversation about what the wishes for their care turns out to be and yet, the majority of the time, the patients have to initiate the conversation. We've got a long way to go.

It's a mix of anxiety and discomfort. We want to be as optimistic as possible and not talk about what happens if your health worsens. It's also uncomfortable for us, and can be for the patients too. So we avoid the difficult conversation. And yet, our survey showed that when people had that conversation with their clinician, their care was rated three quarters excellent or very good. When that conversation didn't happen only a quarter found that their care was excellent or very good, let alone in line with their wishes.

On the subject of conversation, people seem much more likely, according to the survey, to talk to family members about end-of-life planning, but even then the conversation is usually about who's going to make the decision for them — but not about whether they want to go on life support or what their priorities are for that last period of life. Are there signs of progress there or not?

Well, you gotta remember where we were. Go back just five years and we were still arguing about whether this conversation was a death panel. Talking about what you were willing to go through or not for the sake of more time — we still considered that you shouldn't go there. Now we're turning the tide because that conversation is not about, what do you give up, it's really about, what are we fighting for, and I think that we're seeing the first signs of change in the survey data. But the underlying indicators still have a long way to go.

Most of the people who responded to the survey were women. And older, white, married women are the ones most likely to make an end-of-life plan with family members. How do you get more men involved in the conversation?

Yes, men are much less likely than women to have this conversation, and those with only a high school education are less likely than more than high school. Minorities are also less likely to have these conversations.

If you think about it, those are the people who most distrust that people in the system are actually going to fight for them. They are often the people who feel the most looked down upon and the most excluded. So our ability to say, "No, you have a voice, and we actually care what your wishes are for your quality of life and not just your quantity of life, and we're going to fight for you," when you have that conversation -- the survey indicates we still have a long way to go.

We need to get to the point where people regard this as a normal conversation and not a sign of we're just trying to give up and walk away.

There also needs to be greater conversations between spouses, right, because as I read the data it seems like spouses just assume that their opposite will know what they want at the end of life so they haven't gotten around to talking about it.

That's right, the vast majority of us will come to the end of life with someone having to make a decision for us. Often that's the person's spouse and often, despite being in our lives day in and day out, we don't have the big picture conversation.

I had this conversation with my wife and we found we had very different opinions about life. I was of a view that I could be Stephen Hawking. I could be completely paralyzed, unable to be physically connected in the the world, but if my brain was working and I could communicate with you, and I knew who I was and I remembered what was going on in my life — then keep me alive, keep me going.

My wife said that's not the way I would look at it. Her view was, it doesn't matter to me if my brain is working. I don't have to know who you are. She sees herself as a child of God and says, 'If I'm happy, and you know what that looks like, keep me going. If I look like I'm not going to be capable of joy and happiness, then let me go." That was really meaningful and important and as we go on through life, we will continue to have that conversation.

So do your end-of-life plans take into consideration your thought processes?

Absolutely. We just redid our advance directives to take into consideration our own values, but it's really about the conversations more than the paperwork. I wrote about one person in my book who said, 'If I could eat chocolate ice cream and watch football on TV, that'd be good enough for me," and that to me was the best living will ever.

What is the minimum quality of life that you'd find acceptable? For me, it's to communicate and to be able to connect with people and continue to see the movie of the world as it unfolds. For my wife, it's just to experience joy. Understanding that about one another is so important and makes it so that if that terrible moment ever comes, I know what she wants.

So what's the one task that you would hope that people reading do today to start planning?

It's the first, most basic thing: Pick your health care agent. Who will speak for you when you can't?

And then I'm going to tack on one additional task: Talk to that person and tell them what you really care about, what the minimum quality of life is that you would find acceptable. That is what we need to do.

The survey results will be released Tuesday during a Massachusetts Coalition for Serious Illness Care summit. It will include updates on a statewide directory for advance care planning documents, including a MOLST, and a new medical school curriculum that teaches medical students who to talk to patients about death, dying and end-of-life wishes.

This segment aired on May 15, 2018.