Advertisement

Ed Commissioner Finalists

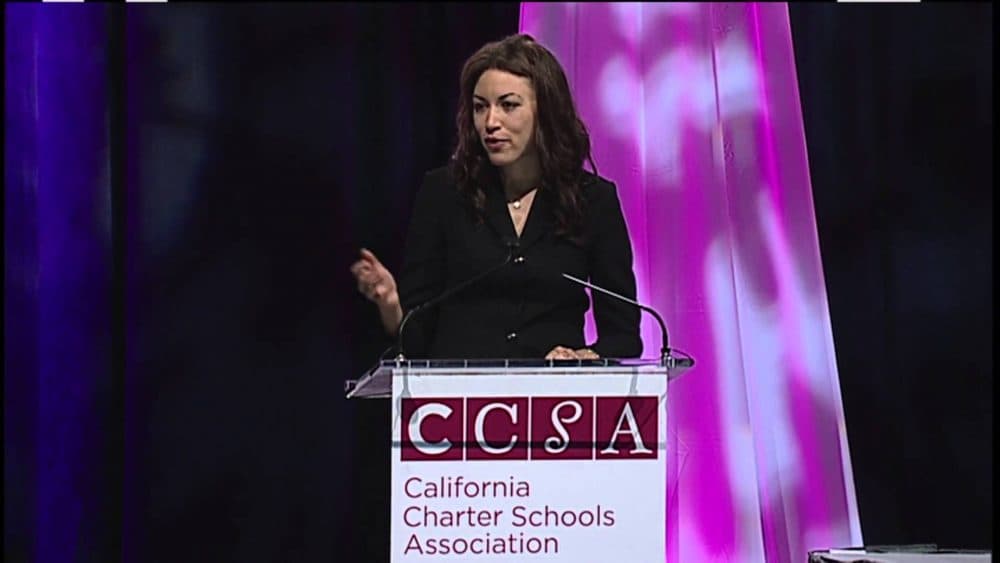

In Penny Schwinn, Mass. Finds A Determined, Divisive Reformer

This is one of our profiles of the three finalists for Massachusetts Commissioner of Elementary and Secondary Education. Each of the finalists will be interviewed publicly on Friday. Board members plan to vote on the next commissioner on Monday. You can read our profiles of the other two finalists, Angélica Infante-Green and Jeff Riley.

The roots of Penny Schwinn's passion for education trace back to her childhood in Sacramento, where her mother taught students less privileged than herself for almost four decades.

In a 2016 interview for the Teach For America (TFA) website, she said that experience built an early consciousness of the achievement gaps that hold back young people across the U.S. In 2004, Schwinn signed up for TFA straight out of the University of California at Berkeley as part of her effort to right those wrongs. (All three finalists started their education careers as TFA teachers.)

At 35, Schwinn is the youngest person being considered for the role of Massachusetts education commissioner. But of the three finalists, she also has the most packed reformist résumé.

If she’s appointed, she would bring a track record of taking on difficult assignments in multiple states — and a legacy of controversy — to Massachusetts, which voted two-to-one against additional charter schools just over a year ago.

It will fall on members of this state's Board of Elementary and Secondary Education to decide how to balance the glowing recommendations of many of Schwinn's colleagues against the upset of some parents and advocates in her wake.

After Short Tenures, Schwinn Kept Moving Up

Schwinn was only five years out of college when she founded a charter school, Capitol Collegiate Academy, to serve mostly low-income students in South Sacramento. In 2015 and 2016, she studied at the Broad Academy, a top incubator for ambitious school administrators that has also been criticized as spreading a corporate approach to education management. And Schwinn is the only candidate with a doctoral degree, a Ph.D. from Claremont Graduate University, awarded in 2016.

In the TFA interview, Schwinn shed light on the achievement-gap dilemma as she sees it: “There is nothing in my professional or personal experience that suggests that the mission we have is not totally possible to achieve. Everything says that it is, and that we know what to do.”

Then Schwinn added: “But what becomes increasingly more clear each and every year is just how hard it is to do what works at a level of excellence.”

After years in Sacramento, Schwinn first began putting her ideas about narrowing the achievement gap to work at the state level in Delaware in 2014.

Under the state's then-education secretary, Mark Murphy, her responsibilities centered on creating a regime of measurement and accountability in the state. She oversaw Delaware's rollout of the Smarter Balanced exam — the assessment aligned with the Common Core — in 2015.

"Dr. Schwinn has a heart of gold," Murphy said. "She was a person on my team who I was able to always count on."

She also implemented the state’s “Priority Schools” program, which used standardized-test scores to target a few urban schools for a battery of "turnaround" reforms — like off at least half of their teachers, while raising salaries and promoting flexibility for new school leadership. That program resulted in a drawn-out and acrimonious standoff between state and some district officials.

For Kevin Ohlandt, a Delaware parent and education blogger, Schwinn's single-minded focus on that kind of accountability was damaging.

"I'm not a fan of standardized testing. And I believe that they're used more to test, punish, label and shame schools" than to help them, Ohlandt said. "And Penny was all about that."

Ohlandt points out that Schwinn has served in six major education roles in three states in the past 10 years: principal, superintendent, school-board member and deputy commissioner.

"The fact that she's moving around the country is very much a concern, because it shows that she kind of comes into a place, causes problems and then leaves," he said.

Schwinn's then-boss, Mark Murphy, categorically rejects that criticism.

"When I look at Dr. Schwinn's career, what I have seen is her willingness to not only do the hardest work to help her children, but also her ability to take on greater levels of responsibility [at each new role]," he said. "That in and of itself shows her incredible courage.”

Controversy Over Special Education

Schwinn's career serves as a kind of ed-reform Rorschach test: her accomplishments look different depending where you stand on education policy.

That pair of opposing perceptions cropped up again in Texas. Schwinn began as the deputy commissioner for academics at the Texas Education Agency (TEA) in the spring of 2016. That fall, the Houston Chronicle reported on the state's fast-declining special education enrollment. It attributed the decline to an effective 8.5 percent cap on special education services that resulted in "the systematic denial of services ... to tens of thousands of families."

Though the decline substantially predated her arrival in Texas, Schwinn took on another difficult job: as the TEA's point person on those allegations.

In a November 2016 letter to the U.S. Department of Education, she insisted that what was perceived as a cap was instead a simple measurement.

"Allegations that TEA issued fines, conducted on-site monitoring visits, required the hiring of consultants, etc. when districts provided special education services to more than 8.5% of their students are entirely false," she wrote in the letter.

Late last year, Laurie Kash — then the TEA's new director of special education — alleged in a federal complaint that Schwinn played a part in awarding a controversial, $4.4 million no-bid contract to a private firm based on a personal relationship with its CEO.

Lisa Flores, the parent of a child with autism and a member of the steering committee of Texans for Special Education Reform, believes some of Kash's charges are substantiated by documents her group discovered.

"What they were going to do was buy [individualized education program] data from districts without parental consent or knowledge," Flores said. "And Schwinn was the primary person in pushing that through."

That contract was eventually terminated before its completion. But an internal TEA audit that concluded in December found no wrongdoing, concluding that Kash's "charges were made without basis and were not supportable."

That said, the U.S. Department of Education issued a finding earlier this month that the TEA's approach to special education "failed to comply with Federal law," that the 8.5-percent indicator "resulted in a declining identification rate of children with disabilities in Texas," and asked the TEA to provide a timeline for "corrective action."

As in Delaware, Schwinn's overseer, TEA commissioner Mike Morath, came to her defense in a statement, saying her "background and leadership reflects a distinguished career committed to schoolchildren." The statement from his office concludes, "Commissioner Morath has committed to strengthening student and parent supports for special education. That work continues."

For Flores, who pulled her son from his school in Texas after what she described as a traumatic experience, the idea Schwinn is now being considered for the top education job in Massachusetts is "insulting."

"Massachusetts is, like, number one in the country for special education services. They do a stellar job of seeing to their students," Flores said. "And I think that hiring her would be an extreme disservice to those students."

"She's very good at being relatable and open. But I think she's even better and even more admirable under attack -- because it takes a caring, mature person to respond calmly and to respond with children first."

Tu Moua, a former colleague from the Sacramento Unified School District

It's safe to say Schwinn can expect difficult questions about past controversies during her public interview on Friday. But when the going gets tough, Schwinn shines brightest, said Tu Moua, her former colleague from the Sacramento Unified School District. The two women collaborated on the district's first "report card" for school performance and accountability.

That process, too, prompted criticisms from teachers and parents in the community — and some of those were, to Moua's mind, unfair. But she remembers that Schwinn bore up remarkably well under the pressure.

"She's very good at being relatable and open," she said. "But I think she's even better and even more admirable under attack — because it takes a caring, mature person to respond calmly and to respond with children first."