Advertisement

As September Looms, Some Of State’s Largest Districts Won’t Return In Person

ResumeAs a statewide deadline nears, school administrators across Massachusetts are deciding how to restart learning in a fall still overshadowed by the coronavirus pandemic.

State officials — including Gov. Charlie Baker and Commissioner Jeff Riley of the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education — have repeatedly recommended that districts invite as many students as possible back into school buildings this fall.

But this week, some of the state’s largest and most vulnerable school districts are weighing or committing to a fully-remote start to the school year — citing the small but worrying resurgence of the virus in state data.

Decision-makers across the state report real anxiety, and a feeling that every decision travels serious risks to the community’s health, children’s learning, or both.

Even as case numbers climb again in the state, officials like Riley are reiterating their in-person recommendation, as long as certain safety protocols are in use. Meanwhile, the state’s largest teachers’ union has pushed for a remote start statewide.

But the difficult judgment call falls, finally, to local authorities: district superintendents, municipal officials, and especially elected school committees.

A Remote Start To School

Last week, the city of Somerville — home to nearly 5,000 students — declared that its public schools will remain fully remote for at least the start of the fall semester.

On Radio Boston Wednesday, school committee chair Carrie Normand acknowledged the risk of pandemic-related learning loss among a whole generation of students.

“We know kids learn best in person. We know our teachers want to be in schools with our students. We know parents need to work,” Normand said. “We also need to consider the health concerns first and foremost… It’s mind-boggling.”

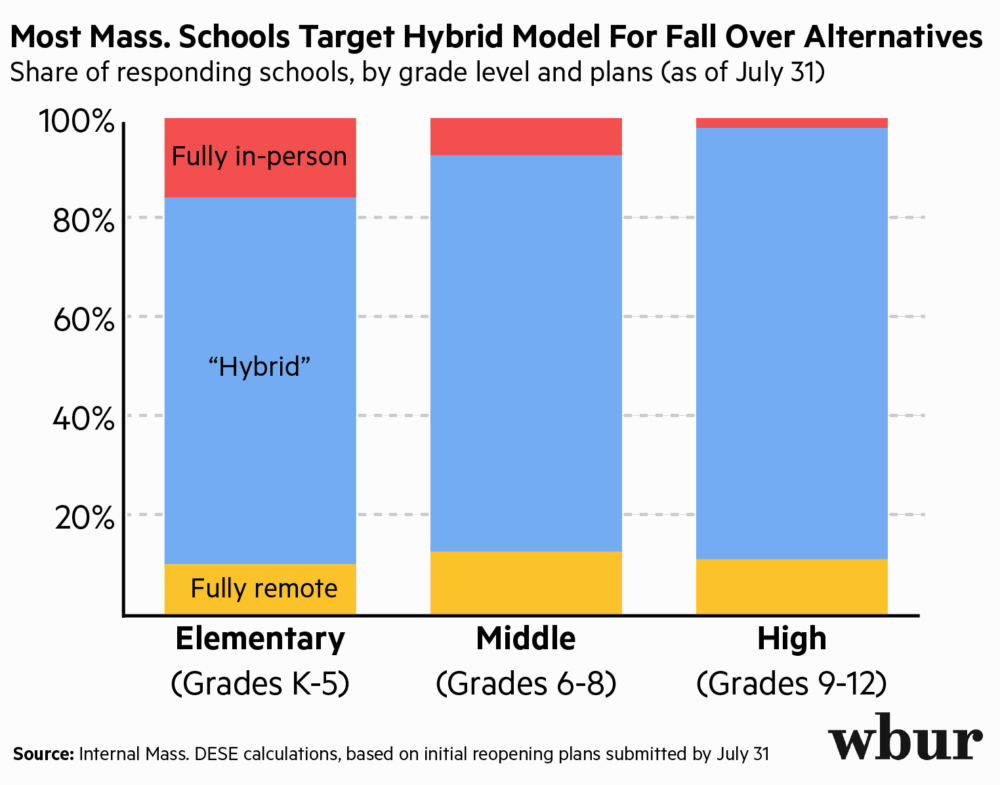

A review of more than two dozen district plans in Massachusetts show that a majority are hoping to implement some version of a hybrid model this fall, with some slight differentiation by grade level. State data based on districts’ preliminary plans submitted before a July 31 deadline reflects a similar conclusion.

But this week, at least five of the state’s largest districts announced plans to follow Somerville’s lead and begin the school year entirely off-site.

Among them are several communities with large immigrant populations hardest hit by the pandemic so far. This week, officials in Revere and Lynn — which have the highest rate of positive COVID-19 tests in the past 14 days among large communities, both around 6% — committed this week to keeping its school buildings closed to start the year.

On Thursday, Almi Abeyta, the superintendent in Chelsea Public Schools recommended a fully remote start to the year, pending a vote of the city’s school committee on Tuesday. And other large districts — including Lawrence, Pittsfield and Brockton — have ruled out bringing all of their students back into the classroom.

Jess Silva-Hodges, a spokesperson for Brockton Public Schools, said that decision wasn’t based entirely on health concerns.

“We do not have the staff to accommodate the extra classes that would be required under a full return,” Silva-Hodges wrote in an email to WBUR. In June, Brockton — which has long struggled with budget deficits — laid off 24 teachers and eliminated 105 other positions, due in part to uncertainty about the amount of state aid coming in the fiscal year ahead.

In Everett — where the majority of the over-7,000 students are labeled “economically disadvantaged” in state data — the first academic quarter will be remote. The district hopes to pivot to a hybrid model for the second quarter, running from November to January, then aim for fully in-person learning.

Frank Parker, a member of the Everett School Committee, said the plan could be “tweaked a little” between now and Aug. 14 — the new deadline by which districts have to submit final and comprehensive fall plans to DESE.

Still, Parker called this week one of the hardest he’s had across many years on the school committee. “You’re making life decisions, from a health standpoint,” Parker said. “You want to be conservative.”

Asked if state leaders’ stated preference for in-person learning shaped his vote, Parker quickly answered no. “We had to come up with a plan that was the ‘Everett plan’... that made sense in Everett,” he said.

Since the pandemic broke out in March, Everett has reported 1,894 cases of COVID-19 — more than double the state average, on a per-capita basis. Now that number is climbing again.

And Parker said the city’s demographics make an in-person start fearsome.

For instance, he pointed to Everett’s high rate of district-to-district transition, involving around 20% of students each year. Many of those students circulate through neighboring districts: especially Revere, Chelsea, Malden and East Boston, all comparatively hard-hit by the coronavirus.

Also, Parker pointed to Everett’s many blended households. “We’ve got a substantial population where elderly grandparents, or aunts and uncles, are now caretakers for these children,” he said. “That’s one of my biggest concerns. If the grandmother has custody of the child, what happens if that grandmother gets sick?”

Why Reopen Physically?

In his news conference Friday, Gov. Charlie Baker admonished districts planning to go the all-remote route.

Speaking of the youngest students, from kindergarten to third grade, Baker said: “Most of the tests and the studies that have been done make pretty clear are least likely to be infected in the first place… Trying to teach those kids how to read remotely? That’s not how you teach kids how to read.”

Asked to justify his own office’s push for in-person schooling at a virtual panel Tuesday hosted by the Greater Boston Chamber of Commerce, Riley offered his own dire warnings, including rising rates of “suicidal ideation [and] depression” among youth stuck at home, as well as incidents of food scarcity and domestic abuse.

Riley noted that a group of pediatricians has recommended physical reopening, given those health risks and the still-low rates of coronavirus transmission in Massachusetts. And he cited a paper published on July 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Meira Levinson is not a medical doctor but is a professor of education at Harvard Graduate School of Education. She co-wrote the NEJM paper, and stressed some of its nuances in an interview with WBUR.

She agrees with Riley that some of the consequences of the remote-learning paradigm used in the spring were disastrous.

Nationwide, a narrow majority of public-school students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, Levinson said. But “although basically every district across the country pivoted very, very quickly to try to provide meals to students who were remote [this spring], a majority of kids have not been able to get the meals that they’re due, for a variety of reasons.”

She also noted that about 95% of mental-health care treatment for American young people begins with referrals from school. In turn, those are based on observations that become more difficult — if not impossible — in video conferences or email exchanges.

And yet Levinson also emphasized that she and her co-authors, including one medical doctor, only discussed the reopening of elementary schools — based on mounting evidence that children younger than 10 or 11 don’t transmit the virus, or suffer from it, as much as adults.

“We don’t say anything about high schools,” Levinson said, “because it’s clear that older kids’ transmission dynamics are closer to that of adults than to 5-year-olds.”

The paper also called for elementary-school teachers to be classed as essential workers — entitled to “substantial protections, as well as hazard pay.”

Levinson agreed that schools serve an important care function for busy families. But with case numbers climbing again, she also argued that physical reopening in September should coincide with a slowdown, or even a step back, in other sectors.

“It’d be not just sad but, I think, actually unforgivable if we squander the opportunity to provide in-person schooling to [almost] a million kids because we are keeping some indoor restaurants open, hair stylists open,” Levinson said. “Those things really matter. But I think getting kids to be able to go to school matters even more.”

So while Levinson supports a physical reopening of American elementary schools, she wants it to coincide with a collective social reevaluation of schools’ importance — and of the needs of the nation’s most vulnerable.

For now, that means she too feels the pain of the existing inequities — and of the bad choices they leave to families, teachers and local officials: “You have communities of color that will suffer the most as schools remain closed, and will risk the most if schools are reopened.”

This segment aired on August 10, 2020.