Advertisement

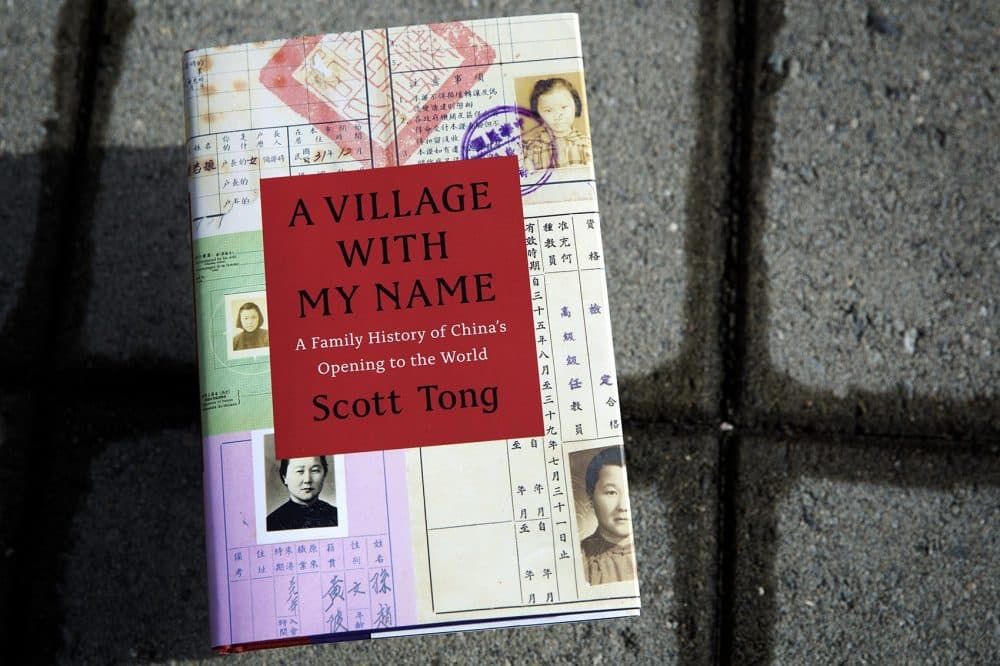

'A Village With My Name' Traces China's History Through One Family's Stories

Resume

Scott Tong is a Marketplace correspondent based in Washington, and was Marketplace's founding China bureau chief.

His latest venture is more personal. In his new book "A Village with My Name: A Family History of China's Opening to the World," Tong explores his family's history in China — from his great-grandfather to his adopted daughter — and tries to provide a greater understanding of modern China.

"I got the wrong impression of China when I first got there in 2006, and I'm Chinese," Tong (@tongscott) tells Here & Now's Jeremy Hobson. "I went to international school in Taiwan, and I was forced to learn Mandarin as a kid, so I thought I knew what to expect."

- Scroll down to read an excerpt from "A Village with My Name"

Interview Highlights

On whether people get the wrong impression of China

"What I got when I first went there is this disease people talk about called 'skyscraper syndrome.' You go and it looks like Dubai, it looks like Manhattan, it looks fancy and China just looks like the story of today. It's a right-now story, or the story of the future. And really what you lose is the longer story of where China has come from. And so it took me really a while to try to understand the right question to ask, and it really wasn't until I left China four years after being there as a reporter that I thought, 'You know what I really don't understand well enough, is the longer story of how China got here,' and I had a hunch that some of my family members were part of that story, and so that's kinda what led me to start this book project."

On trying to find Tong village, where his great-grandfather lived

"A lot of Chinese villages are disappearing now. So when my dad and I went to go find the Tong village, we weren't sure it really existed. It took us a full day of asking around, asking people in the street, and in the end, we stumbled upon a person who said, 'Oh I think I've heard of this place, and I know a guy,' and he pulls out his phone, and then comes into the van, we pick up the next guy who also comes into the van and then we pick up a third guy, and this is kinda how it is in places like China. The third guy happens to be the party secretary, so he's the most important person there, and he leads us to this village, which is 100 or 200 people along this kinda sad-looking creek, and it's like a lot of villages in the world. There's no indoor plumbing, there is electricity there. It's a pretty basic existence. But, you know, on the other hand, it's really something where you finally see where you're from."

On challenges he faced researching the book, and resorting to sending a young girl into a school his grandmother attended to take pictures

"Most institutions in China are gated, and they tend to have a guard. So I tried to go in, and I had my story prepared in Chinese, of this grandson of China going back, and this is the school my grandmother went to, it was run by American missionaries back at the time, and the guard didn't let me in. I failed, which happens a lot. I tried to talk my way in and I failed. So, you know, I'm not really thinking very clearly. I'm just desperate. I hand my iPhone over to this 12-year-old, trusting that she's gonna do what I say, and she actually goes in and she snaps a bunch of pictures for me, runs back out and does the little favor.

"It's one thing to be a foreign reporter in China, and it's a more adversarial relationship. A lot of Chinese people are pretty nationalistic, and they think the foreign media have something against the Chinese people and the Chinese government. But when I went back to research, work on this book, as, you know, ethnic Chinese from overseas coming back a couple generations later, I found the reception in China to be a lot different. I mean that was just kind of one of several moments where kind of the soul of China came out a little bit, because very often, people will not do something just to help you, just to kinda do you a favor — culturally it doesn't happen very often. It happened a lot when I went and I said, you know, 'I'm just trying to understand my longer family story here. Will you help me out?' "

On why he says news Chinese people get about the rest of the world is distorted

"The framing of it is often that, 'A lot of the world is against us,' and the U.S. kinda factors in the center of a lot of those conversations. So in the state media, it's very often an us-against-them kind of narrative that the Chinese people have. So that really doesn't tell the whole story, obviously, of what's happening in the world. The reason it works I think is because there is very often a national pride in China, because not too long ago, a couple generations ago, a lot of the world seemed to be against China. China was unbelievably weak at the end of imperial China in the early 20th century, it was going through wars, a lot of other either attacks from the outside or self-made problems there. So China was really weak and left behind by modernity, and that mindset I think ... a lot of people still have that mindset in China. So what the official media organs play to is 'us against the world,' and that often is how it's portrayed."

On how sure he is that what he discovered about his family in China is true

"I didn't get the whole story, and certainly Chinese nationals — because of the recent past — have reason to not always tell the whole story. The centerpiece of how Mao [Zedong] controlled China was to pit people against one another, and undermine trust in society. So that lack of trust is still embedded in mainland culture today. It's a pretty low-trust society. So people have understandable reasons I think to not always tell you the whole story.

"So I just took my communication, independent thinking, critical thinking, journalism skills, whatever I had in my pocket, and tried to apply them to what I was hearing from different family members. Now in some cases, there were documents that would support what I was finding that were consistent with what I was finding. When it was just one or two persons kinda telling me the story, there is uncertainty to that. And I try to be pretty clear with you, the reader, that I think this is what happened with the story. But in general, with the key members, kinda the five people across five generations in my family that I kinda try to build the story around, I'm pretty sure of most of the story, because it's confirmed in a bunch of different ways. But like reporters going anywhere, you have to have the healthy skepticism, even when it's your own family."

Book Excerpt: 'A Village With My Name'

By Scott Tong

Globalization drifts in and out of fashion, often quickly and without warning. As I write this in early 2017, we are living in quite a moment here. The modern connected age of open borders and markets is being vilified in ways I’ve not seen in my adult life. Raising drawbridges appears on the ballot wherever I look, and in the States, the handy new epithet is “globalist.” Where this all leads is impossible to know, and in any event I’m not in the predicting business (there are books and investment advisors for that kind of thing). But one thing is clear: much of the angst, ambivalence, and outright hostility toward today’s interlinked world has to do with China.

Without question, the mainland has benefited from global interconnections, paradoxically because its workers have been poor for so long and thus willing to work for what you and I consider peanuts. It seems to have happened quickly. China frequently is cast as a newcomer powerhouse to the top division, emerging out of nowhere. You know the framing of Instant China: Mao dies in the mid- 1970s, Deng Xiaoping takes over soon after, and the story starts there. Anything relevant is After Deng, AD.

Instant China makes for snappy, compelling stories. If you’re reading this, there’s a reasonable chance that you, like me, have parachuted into the mainland for a few days and heard a memorable life story of a cabbie, bond trader, or grubby dumpling seller. That person’s fortunes turned dramatically after Deng’s policy reforms, known as “reform and opening,” or gaige kaifang. Well- intended mainlanders can gaige kaifang you into submission: Gaige kaifang delivered economic and geographic mobility. It allowed for private property, for nobodies to open vegetable stalls and electronic workshops. Gaige kaifang brought meat to the table. The implication is, whatever preceded gaige kaifang was a lengthy period of numbing suffering that amounts to China’s Old Testament: famines, pestilence, floods, wars, colonialism, political witch- hunts, bound feet, and hyperinflation. The fall before the gaige kaifang redemption.

It’s a very clean story I myself told at times on the radio. My first big profile story in 2005 was of a poor, barely literate farmer in the western province of Sichuan. Mr. Xu, a sinewy man with a deep outdoor laborer’s tan and a crewcut, hailed from the village of Guang’an, the home of Deng Xiaoping. He sought his fortunes in the metropolis of Chongqing, finding grunt work as a porter; he roped people’s goods and boxes to a bamboo stick slung across his shoulders, carrying them to the appointed destination for a negotiated fee. Part human, part mule. He slept in a drafty group house in a shantytown, on the bottom level of a barracks- style bunk bed for twenty. I joined him on a return trip home to his village. Suddenly, Mr. Xu transformed into Big Man on Campus, the self- made tale of a village boy who went to the big city and made good. Mr. Xu used his savings to build the tallest house in the village. Stopping at a neighbor’s house for lunch, he caught me admiring a gigantic wok in the kitchen, perhaps four feet across. Mr. Xu pointed at it and declared: “Mine’s bigger.”

This telling serves multiple constituencies. For the ruling Communist Party in desperate search of legitimacy, it undergirds the essential founding myth that an economic miracle occurred on its watch. For international reporters, it provides a clean narrative to make sense of a big, chaotic place. But I am not so sure now. It’s like taking a snapshot of a flower with a closeup fish- eye lens, blurring the background. The picture is devoid of context.

There is a phrase that captures this context- less view of China, a phrase I’ve appropriated from a global banker and author named Graham Jeal: skyscraper syndrome. Wowed by a masculine highrise, trophy bullet train, nineteen- course feast, or airport auto- flush toilet, an observer looks at China and vacates rational thought. He or she moves on to a series of regrettable business or personal decisions, and returns home convinced the mainland has taken a controlling stake in the universe. China is, well, different. Eventually for those who stay, the fog begins to lift. The toilets in the trophy high- rises aren’t fixed quite right. The buildings stay vacant, and the workers inside underperform. A more nuanced picture starts to come into view.

At this moment in time, it’s worth looking at China and its place in the world with fresh eyes. A Village with My Name is my own pursuit of a useful historical perspective, a project that began after I returned to the United States in 2010. It’s a tricky undertaking, given there is so much history to consider. “The Chinese people have five thousand years of history,” one of my first Mandarin teachers lectured to me in 1980— a line that has been repeated to me five thousand times since. But how can a new story about China be so very old? How relevant is all that mind- numbing history of emperors and dynasties to today? Where did today’s China really come from?

My suggestion here— which, to be honest, reflects the thinking of many intellectual historians— is that critical roots go back to a prior heyday of globalization: the century before World War I. Going back at least to the nineteenth century, self- interested Chinese (and foreign) nationals took the seeds of modernity and sprinkled them on mainland soil. As it turns out, some of these first movers are on my family tree. If you know anything about China’s recent past, you know that only some people were rewarded for looking outward. Others paid a heavy price when political winds changed and a newly xenophobic China slammed its doors to the world.

The upshot of that decision was to delay progress. Fundamentally, China’s is a story of coming late to modernity. Many Chinese have told me: We came late to the industrial revolution, late to the digital revolution. We are not going to miss the next one.

Reprinted with permission from A VILLAGE WITH MY NAME. Published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2017 Scott Tong. All rights reserved.

This article was originally published on February 05, 2018.

This segment aired on February 5, 2018.