Advertisement

Why A Wheelchair Cannot Come Between Love

Resume

Ben Mattlin was born with an incurable degenerative condition called spinal muscular atrophy, which has prevented him from walking, standing or, as he has aged, using his hands. But like many people who have disabilities, he did find love.

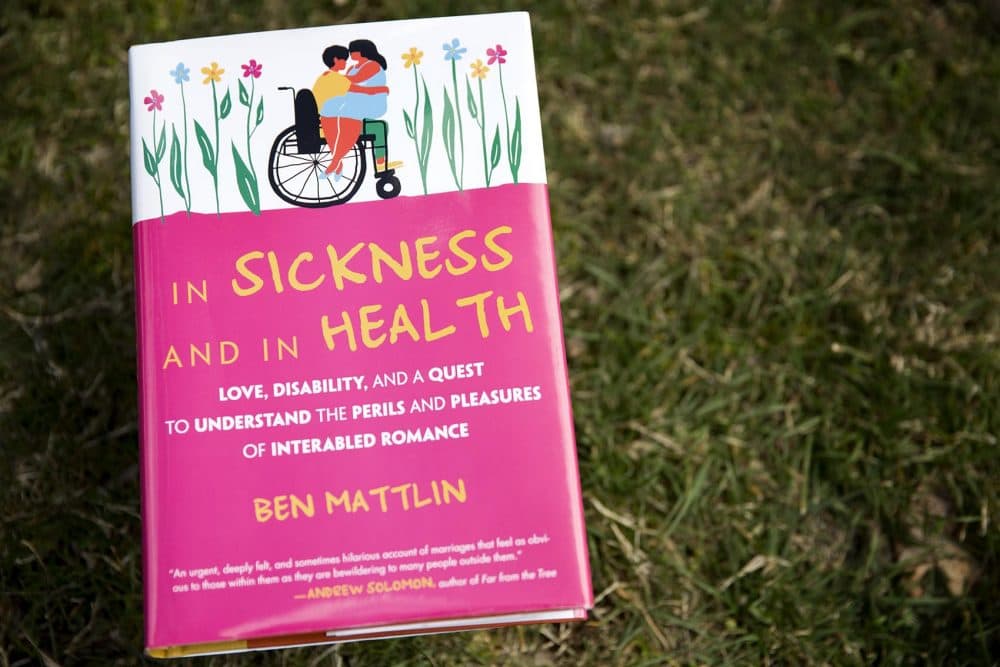

Here & Now's Lisa Mullins speaks with Mattlin (@benmattlin) about his story and other examples of "interabled" couples he highlights in his latest book, "In Sickness and In Health."

He says people with significant disabilities who, like him, found love with able-bodied partners often face discrimination from others who say their partner is "a saint" for being with a disabled person.

"That kind of view is based on an assumption of prejudice that the disabled person is a deficit, and that's not really fair," Mattlin says. "We are so much more than our physical limitations. Yes, there are situations, of course, where it doesn't work out, but my disability was, part of it's made me who I am, so to separate it out really makes no sense."

Interview Highlights

On if he was ever concerned that love was unattainable for him

"Honestly no. I was cocky. I was overconfident, perhaps, perhaps naive. Although looking back now at my age, I kind of wonder about that. It's the reason I wrote the book. And so I kind of wanted to examine how it happened, why it's lasted so long, and instead of just looking at me, at us, that's why I brought in other couples to get a sense of how things are these days."

On if he feels like his marriage is an equal partnership

"Well, I make a point of it [to give back to her]. I make sure I do. I mean, one thing I do, I think, in our relationship, I tend to be the connection with the outside world. I mean, I keep track of family birthdays, keep in touch with cousins and distant relatives, and the finances. I pay all the bills and take care of the taxes. I've tended to often to set the agenda. I think, you know, 'What's on TV tonight? Or what movie should we go see?' That kind of thing. So there's much emotional support that I give her and a sense of humor, and every weekend, we do the crossword puzzle together. And you know, we are a team. We are a partnership."

On how having kids changed his relationship

"Well, like any couple I guess kids are time consuming and expensive, and of course, bring tremendous, not just joy, but, you know, a sense of purpose. There were rough times when they were small — when they were babies — and my wife had to do more of the physical stuff, but I made sure I contributed. I found ways to play with them and watch them in the tub, tell them stories, sing them songs. I learned how to change a diaper. Though I couldn't do it physically, I could direct someone to do it for me if need be.

"I didn't want to be passive or lazy about it. I wanted to be an equal contributor, a participant, and I believe I have been."

"There's much emotional support that I give her and a sense of humor, and every weekend, we do the crossword puzzle together. And you know, we are a team. We are a partnership."

Ben Mattlin

On how sex factors into "interabled" relationships

"There are some people who grew up with their disabilities whose parents yes told them, you know, 'You're not gonna ever find love. You're going to be with mom and dad forever.' Maybe the parents mean well to protect the kids from disappointment, but it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. What was kind of neat for me to learn is that, you know, nowadays, young people, it's all online. So even Shane in my book is 23 I think when I first spoke to him. He blogged, and he was able to be honest about his limitations but also get his personality, I guess, out there online. Obviously some people care more about sex than others, or there are degrees of intimacy that people can enjoy. But it's important really actually to stress that these couples are lovers. They are physical with each other, intimate in certain ways. And that part of the problem we talked about before calling one a saint or whatever, it tends to desexualize or infantilize the disabled person, and that's really not fair or accurate."

On what he would tell a disabled person looking for love

"I guess I would say, 'Don't give up hope.' It may not be easy, but one thing my book I hope shows — and it's a testament to — [is] the fact that it is possible for a variety of situations, types of disabilities. It does happen. People do find love, and they do make it work."

Book Excerpt: 'In Sickness And In Health'

By Ben Mattlin

Back in 2012, I had the good fortune of publishing a book. That book. You know, the one able-bodied people are always telling crips to do because they’re sure it would be “so inspirational!”— in short, a memoir about growing up with a severe disability and

somehow prospering.

Indeed, being unable to walk or even scratch my nose hadn’t prevented me from going to Harvard. I was one of the first quadriplegics to matriculate, if not the first (bragging rights not yet fully established). It hadn’t prevented me from marrying (and staying married for twenty-six years now, and counting), having two delightful children, and forging a career as a freelance journalist. But of course, you already know all that, if you’ve read my first book.

Miracle Boy Grows Up introduced people to spinal muscular atrophy, the neuromuscular incapacity with which I was born. I have no muscles but full sensation (more about that later). I learned to live with it just as the world was learning to live with people with disabilities as a political force, a civil rights movement. But what to do for a follow-up? I’m not Mary Karr! My life only has one book in it.

Some readers were insistent. A number of them suggested I delve deeper into my marriage, expose the secret spats and salacious highlights. But I didn’t want to turn myself and my wife, Mary Lois (who does not have a disability of her own, poor thing), into gossip fodder, thank you very much.

Yet the nugget of an idea began to form.

Surely, we can’t be the only “interabled” couple, for lack of a better term. Quick research showed that, although the statistics are unreliable, there are many marriages between people with and people without disabilities. And as the population ages and medical and technological advances enable people to survive illnesses and injuries in greater numbers than ever before, more and more folks are finding themselves in more or less our situation.

To the media and general public, though, this kind of amatory partnering is often treated as an odd phenomenon. Not long ago, the cover of People magazine flaunted the marriage of Gabby Giffords—the brain-injured former congresswoman—and her husband, astronaut Mark Kelly, as a “special but unconventional love affair.” Is that supposed to be flattering? This treacly hooey could give you diabetes!

I also keep hearing and reading about the aging population, this wave of debility and decay that’s creating a “caregiving crisis” (New York Times, February 26, 2014, among others). To me, this trend dovetails with the worrisome news of veterans who are returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with disabling injuries—the wounded warriors with young spouses who don’t know how to cope with their disabilities.

I know strangers frequently regard M.L. and me as either tragic or noble. (We’re neither.) At the root of all this wonder and puzzlement, I think, is simple curiosity: How do they get by? Will they be all right? To put it another way, what people really ponder is: What kinds of pressures does disability put on a marriage? (The former activist in me protests: These quandaries are predicated on outmoded, unflattering presumptions that people with disabilities are nothing but burdens and liabilities! Certainly we bring more to our marriages than our bodily limitations!)

In an age when interracial and interfaith marriages are common, it seems odd that romances like ours still leave people perplexed and awestruck. Many times I’ve heard M.L. calmly explain to the inquisitive, “I simply fell in love with a guy who happened to be in a wheelchair. Nothing noble or self-sacrificing about it.” (In funny moments, she’s added, “It’s not like he was a Republican or something!”)

While this is certainly true, it’d be foolish to deny the challenges inherent in interabled conjugality. Financial challenges, emotional challenges, and—yes—physical challenges. No doubt it was a tad bold and naïve of us to trust that love would overcome all differences—if, indeed, differences need overcoming. Now that we’re past fifty, M.L. and I can concede that some reflection about how exactly we’ve managed might prove fruitful. I myself sometimes wonder: Why did she want to tie up her life with mine? And what gave me—a man who depends on round-the-clock personal-care assistance—the chutzpah to imagine, even expect, he could marry and live a normal life like anyone else?

On the other hand, M.L. and I enjoy an undeniable degree of closeness, a give-and-take that other couples might envy. We finish each other’s sentences, not always correctly but usually close enough. More than that, we can anticipate each other’s moods or reactions to stimuli. She can get me comfortable in my chair when I can’t even figure out how to ask or what to ask her for. As for me, well, I can never understand why, in movies, men don’t know their wives are pregnant until the wives divulge it like a big secret. Weren’t they keeping track of their wives’ menstrual cycles? Don’t all guys do that, or am I the anomaly? (Probably something in between “all guys” and “only me,” but still.)

Is our brand of symbiotic intimacy unique to our in-sync personalities, or could it be a function of our complementary differences, of interabled couplehood in general? Is this, in short, a benefit? (And if so, somebody had better tell those couples who are newly facing disability, before panic and anxiety destroy them!) Did we arrive at it naturally or is it something we’ve developed and honed over time? And perhaps most crucial of all, can it last?

To shed light on these and other related mysteries, to gain a stronger self-knowledge and advocate for others who may be facing similar questions and judgments, I embark on a quest to zero in on the glue that binds M.L. and me, to study what sticks interabled couples together and perhaps simultaneously give hope to those who are struggling with the mating game. I’ll endeavor to accomplish all this through frank conversations with a variety of twosomes at different stages of their romantic lives and from different backgrounds. By coaxing them to share their journeys, I hope to unearth a rich vein of compelling and instructive group-wisdom. My mission, I realize, may reveal something I don’t want to see. Like picking at a scab, I might expose lingering insecurities that remain raw and unresolvable. Yet I hope to come out on the other end with not only a better understanding of my own marital bond but also insights into why certain interabled marriages fail while others survive despite—or perhaps because of?—incredible strains.

I’ll start with my own marriage to M.L. Then I’ll identify other subjects who have something worthwhile to offer and represent a particular perspective. (To be sure, there are plenty of couples in which both members have disabilities, but they’re beyond my scope.) Call my survey unscientific and subjective as all get-out, if you like, but I’m certain these discussions will illuminate a broad spectrum of deep-seated truths—and resolve any haunting, personal doubts about whether M.L. and I are a typical interabled union or something unique.

Excerpted from In Sickness and In Health: Love, Disability, and a Quest to Understand the Perils and Pleasures of Interabled Romance by Ben Mattlin (Beacon Press, 2018). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.

This article was originally published on April 20, 2018.

This segment aired on April 20, 2018.