Advertisement

Almost Impossible

Years before he was a major league pitcher, in the '90s, Jim Abbott was a regular kid in Flint, Michigan, with a birth defect: His right arm ended at his wrist. It was in elementary school that he started to develop a real discomfort with being different.

He remembers kids at new schools recoiling when they saw him. Back when he still used a prosthesis, some called him Captain Hook. When he could, Jim hid his right arm by burrowing it into his pocket. There were many moments of simple frustration.

"I was in a classroom coloring something, so I was writing with my left hand and trying to hold the paper on the desk with this prosthesis, and it ripped the paper," Jim remembers. "I had worked really hard on it, and then all of a sudden, it was torn."

From a young age, Jim loved to throw a rubber ball against a wall for hours. His dad figured out a way for Jim to shift his baseball glove to catch and throw with the same hand.

But while he could handle a baseball, Jim still faced a daily challenge: He didn’t know how to tie his shoes.

"I remember my parents tying my shoes for me and triple knotting them," he says.

It might seem small, but if Jim's shoe came untied at school, there was nothing he could do but ask for help, just the kind of attention he dreaded and that made him feel like an outsider.

When Jim was in third grade, his teacher was Donn Clarkson, a tall, charismatic man who had worked at NASA. One day, Mr. Clarkson pulled him into the hall and said, "I figured it out."

Jim wasn’t sure what he meant, but Mr. Clarkson started untying his own shoes, and Jim followed suit.

"I think he put a film on for the rest of the kids in the classroom," Jim recalls, "and we sat outside in those small elementary school chairs, and he started working with the loops in the laces, working with one clenched fist."

Apparently Mr. Clarkson had used his evenings to invent a one-handed shoe-tying technique.

"I tried it, and then he did it again, and then I tried it, and then he did it again."

After a few days of practice, Jim could tie his shoes. For Jim, it was a victory, one that would quietly reverberate through the rest of his life.

Advertisement

"A lot of people assign these labels to my baseball playing," Jim says. "Courageous, motivational, inspirational, and all these things. So much of it was about generous supportive people who believed that there was a way to do things a little bit differently, and Donn Clarkson embodies that as much as anything that I can recall from my childhood."

In the years to come, Jim’s discomfort in the classroom was outweighed by the thrill of the field, the one place he could be like everyone else.

"Although I wanted to do well in sports," he says, "a lot of that ambition initially came from wanting to fit in."

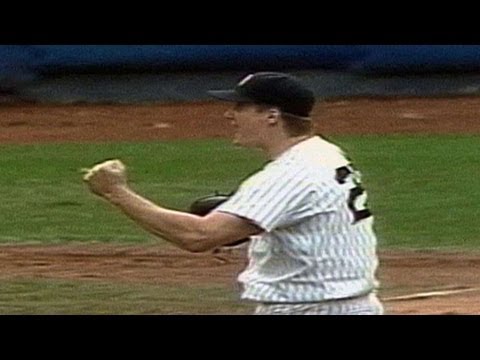

He developed a deep love of baseball and a drive to excel. He could hardly believe it when his dream came true: He reached the major leagues. And he’ll never forget how it felt when, in his first year with the Yankees, he pitched a no-hitter.

"To think that that could be you seemed almost impossible,” he says.

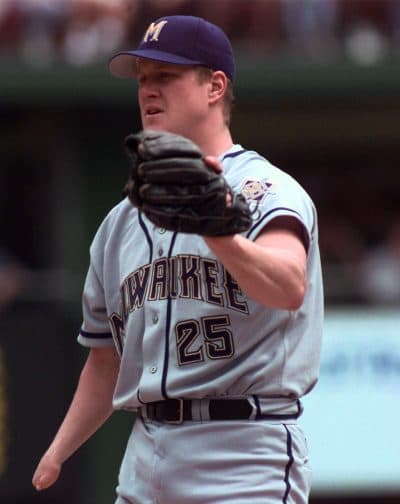

Jim had never been someone who wanted to stand out, but it’s hard not to when you play baseball without a right hand.

"I didn’t want to be the human interest story. As much as I tried to run away from those stories, they persisted," Jim says. "But what also started happening was kids and families started to come to the ballpark, a lot of them missing a part of an arm or part of a hand or facing much different challenges, and much more severe."

Parents wanted their kids to see someone like them. Jim seemed like the perfect role model.

"We'd meet outside of a baseball clubhouse doorway in a dark corridor, and we’d have these encounters."

In the dim light, Jim had to face the part of himself he’d rather hide, and he became a reluctant hero. He also noticed something. A lot of kids asked, "How do you tie your shoes?" So he’d get down on one knee, pick up his laces and show them, "switching places with Donn Clarkson," he says. "I'd be the tall one, I guess, in my baseball uniform, and there’d be a little boy, a little girl."

Eventually it became the first thing he did when he met a child missing a limb — something that said more than words.

"I’ve found a way, and they can do it, too," Jim explains. "I've been on one knee many times, undoing my laces and tying ‘em up again."

Jim retired in 1999, but kids still send him letters and photos.

"Just in the past month, I've heard from three or four different kids who I've communicated with over the years who are going on to play college baseball," Jim says.

"It's part of a chain. It's not me, it's part of Mr. Clarkson. Hopefully it will continue to filter on down the line, and people will always believe in more being possible than less."

Jim’s helped countless kids come to terms with their differences, but in his own life, he still grapples with missing a hand -- a lifelong process, he says — which is why finding himself back in a classroom for his daughter’s preschool career day brought old insecurities to the surface.

"I had every visual aid known to man. I had my gold medal, I had baseball cards, my baseball hat."

At the end of his talk, he was surprised when his daughter raised her hand.

"I called on her, and she said, there amongst her friends, ‘Dad, do you like your little hand?’ "

Jim had never used the phrase "little hand" before. Now he didn’t know what to say.

"It was one of those moments, like Mr. Clarkson trying to teach me to tie my shoes, that I think about often now," Jim says. "Do I like my little hand?"

He fought the temptation to put his hand in his pocket and paused for a moment.

"Yeah, I said. I did."

Jim Abbott's autobiography is "Imperfect: An Improbable Life."

Find Kind World on Facebook or Twitter, or email kindworld@wbur.org to share your story.

This segment aired on June 30, 2017.