Advertisement

As Linchpin Of Project, Mass. Town Of Acushnet Weighs Pipeline Facility

Resume

Three major companies in the energy business have big plans for the small town of Acushnet, population 10,300.

The town, located 50 miles south of Boston and not far from Buzzards Bay, is an essential element in a proposed $3 billion natural gas pipeline expansion project called Access Northeast.

As natural gas transforms the energy landscape in New England, community involvement in Acushnet — support and opposition — is a microcosm of what's happening around the nation.

Addressing Community Concerns

The parking lot of Century House, a banquet facility in Acushnet, is jammed. The entrance on South Main Street glows from the lights of a sign mounted on the side of a truck that reads, "Pipelines are lifelines. Access Northeast means jobs." To this blue-collar community that's a big draw, but it's not work that attracts the crowd this night — it's worries.

Inside, it looks like a high school science fair. Rows of poster boards propped up on easels and video screens on walls with maps and details of the Access Northeast project and artist renderings of the two giant gas tanks to be built in Acushnet — perhaps the largest on the East Coast. Each is bigger than the field in Gillette Stadium and taller than the stands.

Barbara and George Mendonca are from New Bedford and live a mile and a half from the proposed site. So far, they don't like what they've heard about the project.

"The reason why they want the pipeline is just to export gas," Barbara Mendonca says. "It's not going to help the homeowner."

"The gas lines that are running now? If they were to go and block all the leaks, they wouldn't need all the gas that they're going to bring in from this. It would be more gas than just by plugging the leaks," George Mendonca adds.

Dozens of employees with Spectra Energy, Eversource and National Grid — the companies that want to build Access Northeast — stand at the ready to answer questions and set the record straight.

The gas for the project is for export, but not overseas. It would be sent to electric-generating plants around New England. And leaks? They're a problem for local distribution companies that use gas for heat, not the pipelines Access Northeast will use.

What Access Northeast Would Accomplish

"We invited the entire town of Acushnet out to share information about the project and answer questions," says Arthur Diestel, spokesman for Spectra Energy.

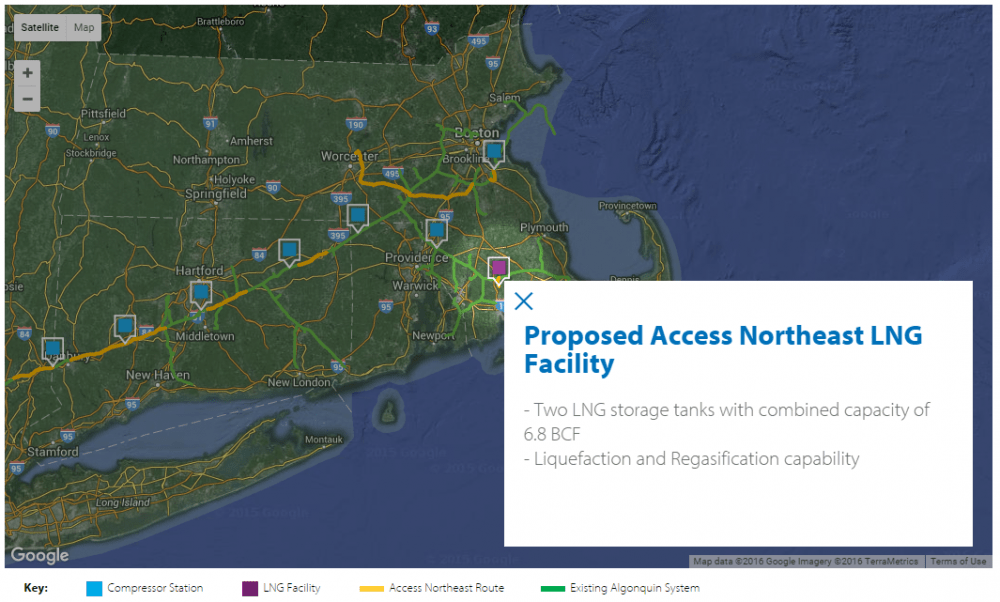

Diestel says the Access Northeast project will tap into the existing Algonquin interstate system and increase the capacity of the pipeline from Connecticut to Massachusetts. That means it would be able to carry an additional billion cubic feet of natural gas from the fracking fields of Appalachia and provide a reliable supply to New England when demand for gas soars.

"The capacity is currently all used by local distribution companies right now for heating and cooking and, on the coldest days of the year, power plants need access to that gas," Diestel says. "This is a tailored solution that utilizes our existing footprint to minimize the impacts on the environment and landowner and will also allow power plants to access the gas when they need it the most."

And in the process, says Diestel, the project will save gas generators and their customers a billion dollars a year, and perhaps a lot more.

Acushnet is the linchpin to the Access Northeast project. The plan calls for the construction of a pipeline three miles long that would deliver gas from the interstate system to a new liquefaction facility at a 225-acre site owned by Eversource.

Eversource spokesman Michael Durand explains that during the fall, when gas is less expensive and the supply plentiful, the plant will turn the natural gas into a liquid, compressing it to 1/600th the volume and store it at minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit in two new tanks.

"Very similar to the two tanks we have in this area now," Durand says. "The only differences — those tanks are for our gas delivery customers, these tanks would primarily be for electricity generators."

But there is another difference, and it's a big one. The two new tanks would be 13 times the size of the existing tanks at the site and twice as big as the LNG tanks in Everett.

'This Is Not Where It Belongs'

Acushnet resident Roger Cabral is with South Coast Neighbors United, a new group opposed to the project.

"Twenty-five percent of New England's LNG is going to be in Acushnet, in a residential community surrounded by homes, surrounded by hospitals, surrounded by schools," he says. "It's the wrong spot for this project. Maybe it needs to be somewhere — this is not where it belongs."

Cabral's big concern is not just size, but safety. He cites the out-of-control leak at an underground natural gas storage facility in California.

"The governor has declared a state of emergency. They've evacuated thousands of homes," Cabral says. "I'll bet those residents were told the facility was safe. I have no opinion other than being aggressively neutral."

Kevin Gallagher is reserving judgment on the new gas tank plan, but as fire chief of Acushnet, he has firsthand experience with the existing natural gas facility in town.

"For the current operation, they exceed federal and state standard," he says. "A 44-year record with no fire-based incidents is one they should be exceptionally proud of. At this point it's too early to chain ourselves to the facility and say, 'Hell no,' and [it is] too early to take out the pompoms."

David Wojnar, chairman of the Acushnet Board of Selectmen, is also reserving judgment. The town stands to collect $10 million a year, maybe more in new property taxes, if Access Northeast is built. It's a third of the town's current budget.

"At the end of the day, you have to [be the] right fit for the community, regardless of the financial implications, so it's important — you have to divorce yourself from the money aspect of it and judge the project on the merits," Wojnar says.

But Acushnet resident Merilee Kelly has already made up her mind.

"I think it's a big project that's really scary for the little town of Acushnet," she says. "If it's necessary, I wish there were a different area to put it."

Kelly is also Acushnet's conservation agent.

"The area where they're talking about putting it is a really beautiful woods," she says. "It's heavily occupied by wildlife and will be impacted, destroyed by this project and it breaks my heart if that's what's going to happen."

A Town That Tells A National Story

What could happen in Acushnet is already happening in towns and cities across the country. The natural gas pipeline business is booming as electric companies retire coal, oil and nuclear plants and replace them with gas-fired generators.

Last year, there were 53 new land-based gas pipeline projects pending before FERC, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. That's twice as many as the year before and six times more than the preceding five years combined.

FERC environmental project manager John Peconom says, "It's great job security, I'll tell you that much. There's a lot of work in front of us right now and a lot being proposed."

But natural gas, which promises a cleaner, cheaper way of generating electricity far into the future, is still a fossil fuel that emits climate-changing gases. As projects proliferate, so do grassroots organizations opposed to natural gas who pass along knowledge of the intricacies of the federal permitting process and use it to stall pipelines and storage projects.

And in Acushnet, which the native Wampanoag named "The peaceful resting place by the water," opponents promise that the battle over Access Northeast has only just started.

Federal regulators won't officially begin to review the plan until the end of this year, and it could take two more years for a final decision.

This segment aired on February 2, 2016.