Advertisement

With Case Backlogs Rising, Immigration Courts Struggle To Protect The 'Vulnerable'

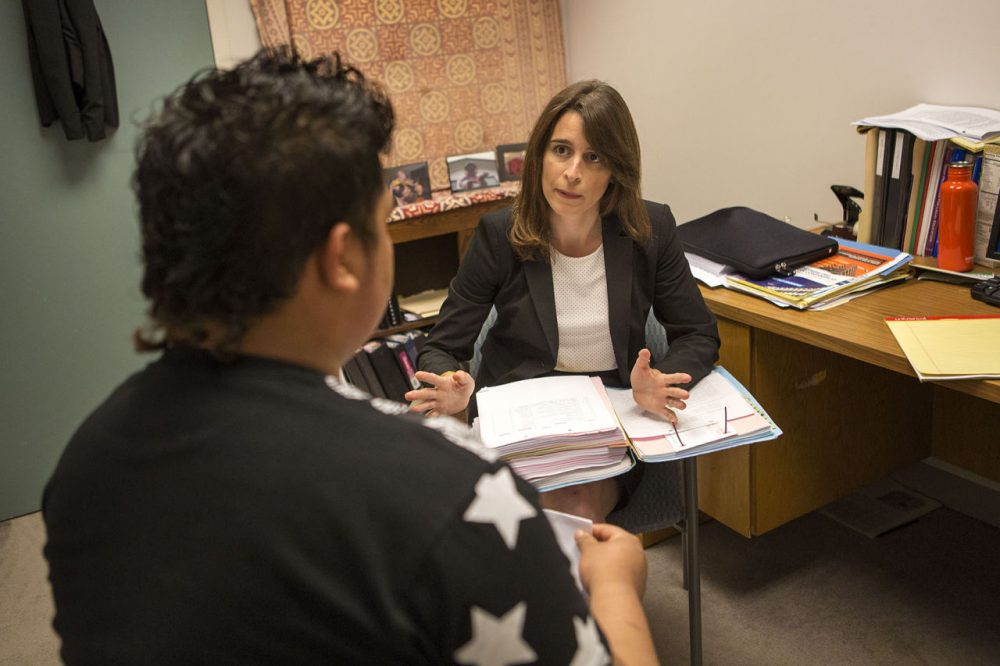

Sitting in a small shared office space at the Boston University Immigrants' Rights Clinic, Sarah Sherman-Stokes, a clinical teaching fellow, instructs a young client from El Salvador about his next appointment in immigration court.

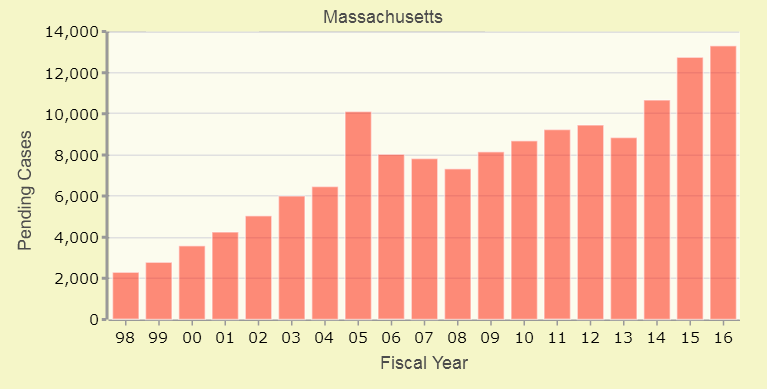

His is one of the about 13,000 pending deportation cases in Boston.

Speaking in Spanish, she asks the young man whether he has any questions or concerns. He says he doesn't and leaves the office with a notice in his pocket for a court date four months out.

For people in the immigration court system, hope and anguish can be measured in backlogs and daily dockets.

And as Sherman-Stokes says, many of the cases involve high stakes.

"People are facing really life or death situations and many of them don't have counsel, don't speak the language and are completely unable to navigate the really complex system of immigration law on their own," she says.

The daily caseloads of each judge in Boston can vary, but with one of the top 10 largest pending deportation backlogs in the country, some judges say there's a responsibility to push through cases quickly.

Eliza Klein is a retired immigration judge with more than 20 years of experience on the bench, including 15 years here in Boston. She describes the volume weighing down the docket for immigrants detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

"Sometimes judges have 15 cases in a three-hour period and sometimes they have 25 cases and sometimes even more," Klein says. "So you don't have at the outset the amount of time that you really need to spend with each person."

Cognitive Issues Make Cases More Complex

The rapid pace of a proceeding can be dizzying for a non-native speaker.

Now, imagine that same person has a mental health issue — what's known by the court as a so-called "vulnerable immigrant."

Alex Peredo Carroll, a Boston-based immigration attorney, recently represented a Honduran man who she believes lacked the comprehension skills to fully understand his deportation case.

“When I first met with him and worked with him a little bit," she says, "I realized that he wasn't really understanding what I was asking of him.”

Peredo Carroll’s client was before a judge after being apprehended by immigration officials for a second time.

“We [his lawyers] felt that there was definitely a cognitive issue with him," Peredo Carroll says. "It was never diagnosed, but his inability to be able to tell his story, you know, certainly affected his case.”

Peredo Carroll says she tried to get a pro bono mental evaluation in the small window of time she had, but she could not.

Advertisement

“The client really was unable to tell his story in a way that would have helped him. I think the facts actually were on his side," she says.

Sitting immigration judges are not authorized to comment on cases.

Peredo Carroll says she believes the judge did conduct a fair hearing but ultimately found no signs of mental incompetence.

Her client was deported back to Honduras, where Peredo Carroll says he fears for his safety.

"When somebody doesn’t understand the process that they’re in, they cannot help themselves,” she says.

No Right To Representation

Peredo Carroll's client had more help than many in the immigration court — he had a lawyer.

Unlike in U.S. criminal court, the government has no obligation to provide lawyers for people in deportation cases.

This means that individuals often represent themselves, explaining their own story, providing evidence and cross-examining witnesses.

So, in the absence of a lawyer, the immigration judge uses his or her observation of an individual to determine whether someone is mentally capable of fully participating in their own proceeding.

"Being able to tell their story is really critical to moving through the asylum system, or immigration system more broadly," says Dr. Diya Kallivayalil, a psychologist at Cambridge Health Alliance, who works at the Victims of Violence Program and who's evaluated individuals in deportation cases.

Kallivayalil says that even in a controlled, psychiatric setting it can be challenging to gauge someone's mental competency, let alone in a busy courtroom.

"The burden of having to do that in an adversarial system, where the patient is then terrified and the judge is trying to do their best, you know the burden is quite substantial and so I think, to some degree, mental illness doesn't lend itself to a quick result," she says.

But quick results are often sought in a system strapped for time and resources.

Some immigration judges say the ability to ensure an individual's mental health can be compromised by the pressure to churn through cases.

A 2007 survey from the National Association of Immigration Judges (NAIJ) found complaints about workload and time constraints to be one of the most commonly cited causes for stress and burnout among judges.

"In those cases where I would like more time to consider all the facts and weigh what I have heard I rarely have much time to do so simply because of the pressure to complete cases."

Example of a judge's response from the 2007 NAIJ survey

"I know that there are people who fall through the cracks because sometimes judges don't pick up on people's inability to actually understand what's happening," says Klein, the retired immigration judge. "There aren't the resources to appoint evaluators and there is not the resource to assign an attorney to represent somebody."

Five years ago the U.S. immigration court's appellate body recognized more needed to be done to protect the mentally incompetent in deportation cases. It handed down guidelines to help judges conduct fair hearings, instructing the judge to watch for certain behaviors.

And in 2013, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the court's governing body, announced a nationwide policy providing additional safeguards for unrepresented detainees, like government-paid counsel and psychological testing.

But so far, these safeguards have only been implemented in a few states.

"Unfortunately, those new procedural protections have not been implemented in most courts across the country," says Sherman-Stokes, the BU clinical teaching fellow. "They certainly have not been implemented here in Boston."

'Nuances At Times Are Going To Be Missed'

“The immigration court system is an extremely challenged tribunal. I often say that we conduct death penalty cases in a traffic court setting.”

That's Dana Leigh Marks, an immigration judge in San Francisco and the president of the NAIJ. She says that immigration courts simply don't have the resources they need to keep up with the caseloads in a system mired in complicated legal matters, including questions of mental competency.

"The immigration court system is an extremely challenged tribunal. I often say that we conduct death penalty cases in a traffic court setting."

Dana Leigh Marks, an immigration judge in San Francisco

“We do receive training, we try to be alert to issues which may be red flags for deeper mental health conditions which are affecting someone, but it's obviously a very difficult context in which to try to make that determination," she says.

Kathryn Mattingly, a spokeswoman for the EOIR, told WBUR in an email that it continues to expand the nationwide availability of judge training, legal representation and mental evaluations to detainees. A review of annual budgets does show a steady system-wide increase in funding.

But Mattingly confirmed that the safeguards for unrepresented immigration detainees with serious mental disorders have not yet been implemented in Massachusetts.

Given the workflow of the immigration court, Judge Marks says the system is, in some ways, handicapped at its core.

"In a system that handles as many people as ours does, with the speed in which our system handles these cases, it would seem unavoidable that certain nuances at times are going to be missed," Marks says.

And in immigration court, some fear that nuance can mean the difference between deportation and reprieve.

This segment aired on March 22, 2016.