Advertisement

Two Families, Two Stories: Charter Schools And Special Needs

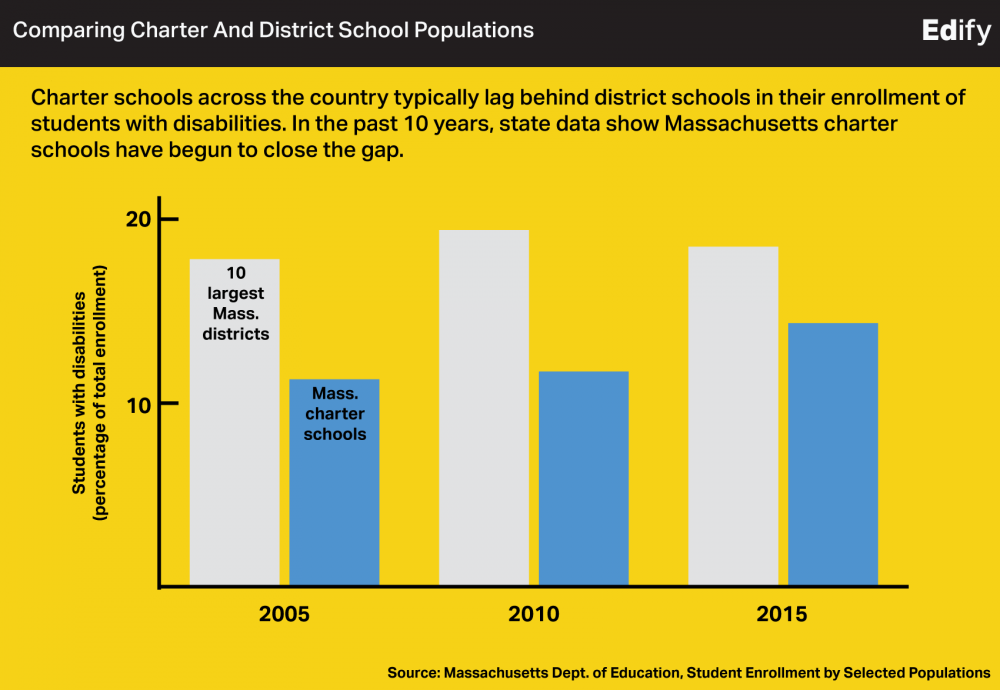

One key point of contention in this year's debate over Question 2, which would lift the cap on charter schools, is whether charter schools serve the same mix of students as district schools. Specifically, opponents have charged that charters serve fewer students with higher needs, including disabilities.

It's a complicated question. But enrollment numbers show that charter schools have begun to close significant gaps between their student populations and those of district schools since the last significant education reform act passed in 2010.

Among other things, “An Act Relative to the Achievement Gap” doubled the size of the cap on charter schools in low-performing districts like Boston and Springfield. But it also put pressure on charter schools to increase their recruitment and retention of high-needs students — including students with disabilities — so that their populations would more closely match those of the sending districts.

In a press conference after he signed the bill into law, then-Gov. Deval Patrick insisted that it would fall to local actors — school boards and superintendents, as well as charter administrators — to make the most of the new law.

“For the sake of the children, commit to get it right,” he said.

But whether the system is getting special education right for every student is of course a thornier question, and the answer depends on whom you ask. There are parents who say their children's charter schools have answered every special need with special attention, and others who say their children were shaken by a charter experience. By the same token, some children are well served by district schools, and others are not.

We spoke to two families about their experiences. Their stories may not be typical — but the variety of conditions that a "special needs" label can connote means that it's nearly impossible to imagine what a "typical" story might be.

From Charter To District School

Mike and Julie Robinson of Mansfield chose Foxborough Regional Charter School in 2011 for their two oldest children: Brendan, then 7, and Madeline, 5. The reason was simple: FRCS had all-day kindergarten and Mansfield Public Schools did not. Today that decision haunts them — and has spurred Mike to become active in the “No on 2” campaign. All three of their children now attend Mansfield Public Schools.

Mark Logan, executive director at FRCS since 2003, didn’t contest the substance of the Robinsons’ account and added that he’s “really, sincerely sorry” that they they left the school dissatisfied. But he defended his faculty and the school's special-education program, which he contends worked especially hard for both children.

"What we try to do is take every kid, and every experience," Logan said, "and try to build programming around that."

The Robinsons saw signs of trouble early on. A few months into the first school year, Julie received a call that Madeline had used a weapon at recess. When the couple arrived on campus, her daughter’s kindergarten teacher presented them with the weapon: a stone about the size of a playing marble that she had thrown across the schoolyard.

“I thought she was joking,” Julie said.

But the incident resulted in a two-day, at-home suspension. It was, the Robinsons say, the first of five or six out-of-school suspensions, and many more in-school ones, for their young daughter over three and a half years.

FRCS staff were the first to recommend that the Robinsons bring their children to a doctor, which is how both children eventually received a diagnosis the parents had not known: Tourette syndrome.

After that, the Robinsons insist, they took pains to educate teachers and administrators about the features of Tourette, sending along reference guides with headings like "What Makes Madeline Tick — And What Makes Her Tic?" But the Robinsons say that even their offers to send experts to the school weren’t accepted, and that their years there were characterized by a pattern of insensitivity to their children’s needs.

When Brendan shouted out in class, they say, his teacher called him a bully. When Julie warned that addressing Madeline’s twirling would only make her feel uncomfortable, she recalls, the school’s director of special education replied, “Sometimes children need to be made uncomfortable.”

Their time at FRCS ended after two episodes they described involving Madeline. First, a staff member interrupted her in the bathroom — which had been set aside as a safe space to "release" her tics — and then forcefully restrained her when she, frightened, tried to run. On another occasion, she was left to lie paralyzed on the floor of an empty classroom while Julie drove to the school to pick her up.

There were bright spots — including a first-grade teacher who doted on Madeline and a new special-ed director who arrived just as they first planned to leave the school: “The very first time we spoke with her was right after she had met Madeline. She said, ‘I don’t understand it. I’ve read all of Madeline’s file, and I thought I knew who she was. But then I meet her, and she’s a smart, funny, kind child.’ Imagine hearing that everything that the school has on record about your child is the opposite of that!”

The Robinsons and FRCS agreed that Madeline should go to a therapeutic school for 45 days, and she stayed there through the end of the school year before enrolling in their home district. The Robinsons say she and Brendan still shut their eyes when the family happens to drive by FRCS’s campus.

But all three of their children are now happy in public school, the Robinsons said, without a disciplinary record to speak of. Mike broke into tears when he described the compassion with which Brendan’s Pop Warner team treated his tics on the sideline: “Do you know what that felt like? That felt like heaven.”

Mike Robinson blames systematic problems with charter schools for what his family experienced: a “perfect storm” combining a focus on academic excellence and a desire to keep costs low.

“Just about every time we had a meeting with the school, we were reminded that our children were consuming the most resources out of anyone in the school,” he said. “That is how we started meetings.”

Drawing on publicly available data, Robinson has argued that Massachusetts charter schools still have a special-education problem. State records do show that some charter schools lead the state in suspending between a half and a third of all their students on IEPs, the individualized education program that schools must develop for all special-needs students, and that more such students — as many as 36 percent — end up leaving certain charter schools early than they do in comparable district schools.

Robinson also argues that charter schools employ fewer special-education professionals per student than district schools. But charter advocates have called that claim “bogus” and attribute it to flawed data.

Thriving At A Charter

And other FRCS parents of students with disabilities came forward with very different stories.

When Shari Kah’s son Kasyn lashed out violently against an FRCS teacher, she feared the worst. But instead of expelling him, the special-ed director and dean of students placed him, too, in a 45-day evaluation offsite. When it was over, FRCS welcomed him back.

After that, Shari Kah said, Kasyn thrived.

Kah’s testimony echoed what I heard at the home of Cara Gillis in Dorchester. Her son Joe was diagnosed with high-functioning autism while in the third grade in Boston Public Schools.

Joe was an academic star, but an evaluation showed he would need extra help with social skills. But as soon as she began to seek that out, Gillis said, she encountered “pushback” from school administrators: “They would tell me, ‘He’s at the top of his class, and he’s not disruptive, so he’s all set.’”

The school year was half over by the time the school agreed to schedule one-on-one meetings between Joe and a counselor. In between, Gillis said, school officials told her there was no need for a special social-skills group at the school, since among the school’s 800 students, there were no others with Asperger’s syndrome.

Gillis said she was unsure about sending Joe to Boston Collegiate Charter School, because she’d heard that charter schools weren’t always accommodating to kids with special needs.

But then she learned that Collegiate actually serves about as many students with disabilities as the Boston Public Schools — and came to see the new school as a godsend.

“I couldn’t believe how child-focused it was,” said Gillis. “It’s a completely different feeling — they were happy to help him, rather than annoyed.”

Gillis noted that Collegiate is strict and that her children have gotten detention more than once. But she said she believes that philosophy is working, and she credits the school's close attention for her son's social progress.

She can hear the influence of the social-skills group in Joe's conversation, she said.

“One time we were walking along, and he said, ‘Ma, I’m just going to talk about sports. I know you’re not really interested in it, but just pretend.’ That must have been something that somebody told him!” Gillis said.

Hard Choices, Complex Answers

These are anecdotes, but they have a common theme: that an unusual sense of risk and anxiety touches parents as they decide on the school to serve their child with special needs. Those high-stakes choices are made on the fly and, at least partly, in the dark. Are students missing something essential that would help them overcome a disability? Worse: Are they suffering further harm where they are?

Under those conditions, you seek out what works — and cling to it.

For Cara Gillis, that means a “Yes” vote is the obvious choice on Question 2. She’s shocked that the race is even close.

And the Robinsons are just as sure of their “No” vote. Mike Robinson readily admitted that there are angels everywhere, including inside charter schools. But his children’s experience, he said, was reason enough not to raise the cap — and served as a lesson about quality control in a school system organized around choice and individual attention.

“We’ve planted lots of seeds,” he argued, referring to the 78 currently active Commonwealth charter schools in Massachusetts. “And some may be flowers, but some are weeds. And I think we need to identify which ones are the weeds before we start planting any more.”

Foxborough's Mark Logan points out that special needs are complex, that every child is different, and that these nuances can get lost in the broad competition between charter and district schools. Whether a school — district or charter — succeeds with a given child often depends on that child's unique situation.

“It’s about whole-child education. It's about social and emotional growth," Logan said. "Those are really hard outcomes to measure, especially when you’re talking about diverse populations."

But when asked if he’s ready to vote “Yes” on Question 2, he laughed. “I believe in choice."

We talked with the Robinsons after they responded to our callout for experiences with charter and district schools. Subramaniam Vincent, a 2016 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow who tweets @subbuvincent, helped Edify create and manage this project, which we will continue to use to inform our education coverage.