Advertisement

Winter Weather Forecast: What To Expect Around Boston

As we close out the month of November, this is a good time to look at what the winter ahead may bring.

Snowfall and the amount of cold are both highly variable in the Northeast. It’s never not snowed in winter around here, so you should expect to shovel in the months ahead.

We'll get to more of what I’m thinking for the winter, but first, here’s what’s normal, and how meteorologists like me make our predictions for a season.

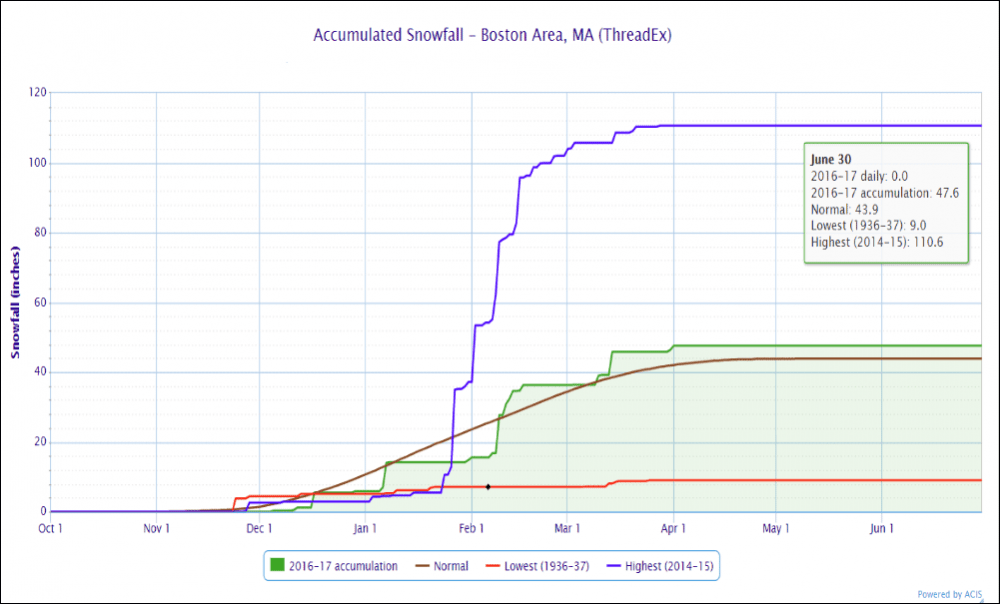

Boston averages 44 inches of snow each winter, but there is a wide range of possibilities for what could occur. (Who could forget the 110 inches in 2014-'15?)

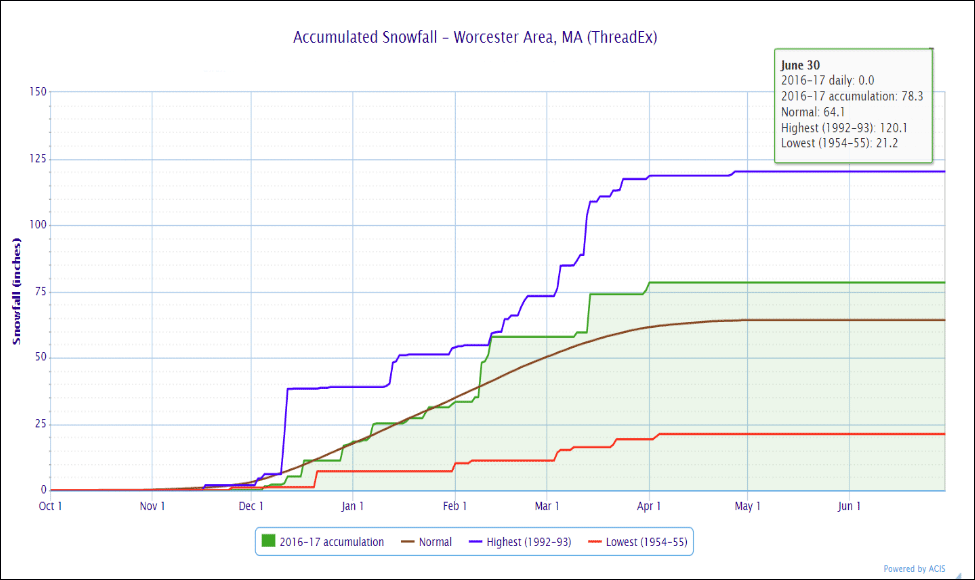

Worcester has more snow than Boston in a typical winter, averaging 64 inches.

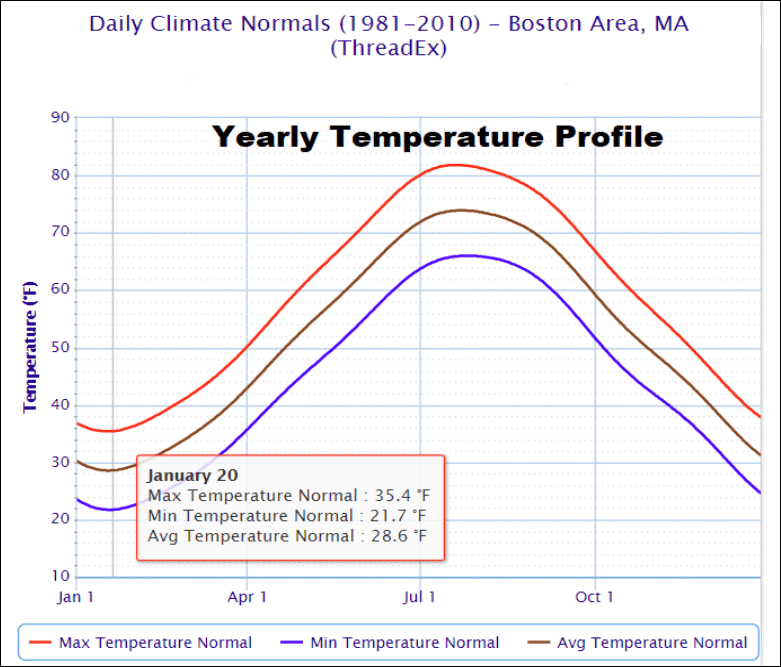

On average, temperatures during December afternoons fall from the lower 40s into the 30s and remain there until later in February, when lower 40s return.

Of course there is a huge range in potential readings all winter, with extremes in Boston from as cold as 18 below to around 70.

Long range forecasting continues to get better, but it's still a very imperfect science. There are many variables that lead to the day-to-day weather during the course of the year, and these variables are especially powerful in the winter.

I like to refer to the variables as switches — each of which can push our region into periods that are cold or warm, and wet or dry. There are years when all the moisture comes along with warmth and we end up with more rain than snow. There are other years when all the cold comes without any moisture, and we just end up cold and dry. If you're banking on a snowy, cold winter, then the moisture and the cold need to be present at the same time. It's logical, but doesn’t happen every winter.

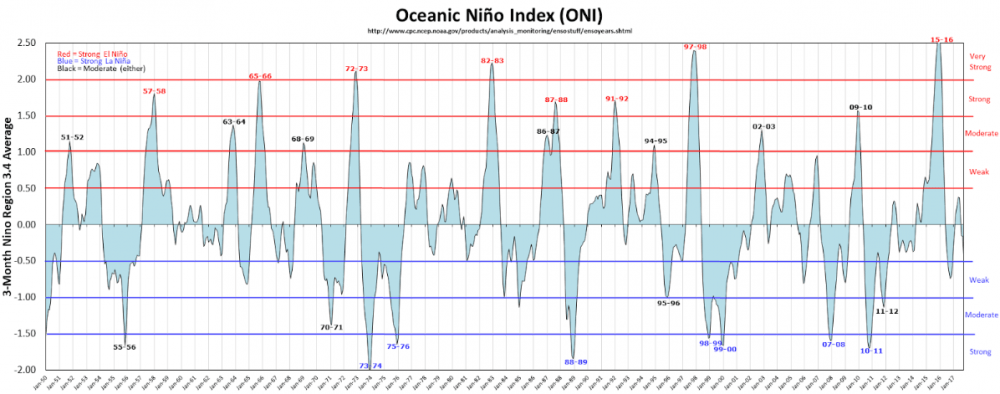

One of the main variables that forecasters pay attention to is El Niño and La Niña. The oscillation between these two is called ENSO, and this year we're in a weak La Niña. Weak La Niña years tend not to be blockbuster snow years for New England, but it doesn't mean that it can't happen. Most of long-range forecast is about probability.

Advertisement

Since long-range forecasts are based on all these different variables, it’s also critical to look at what's happened in the past.

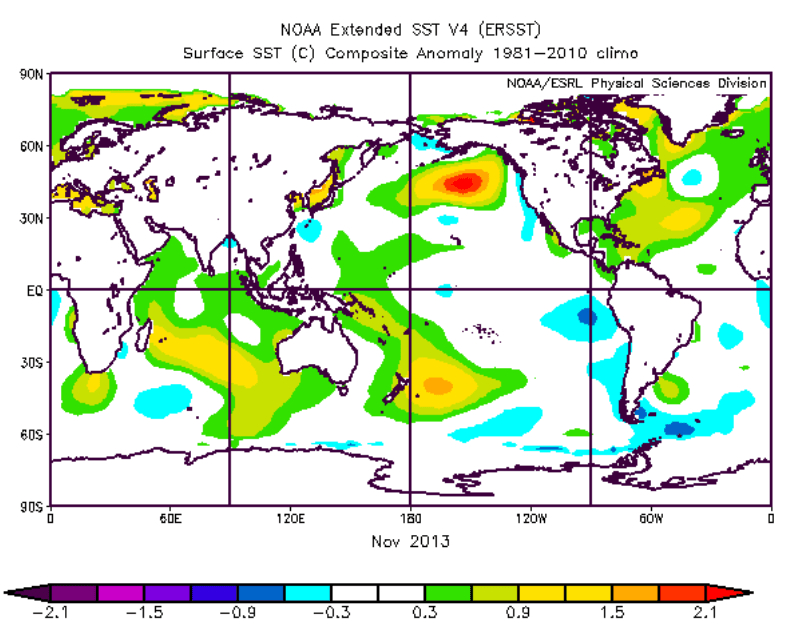

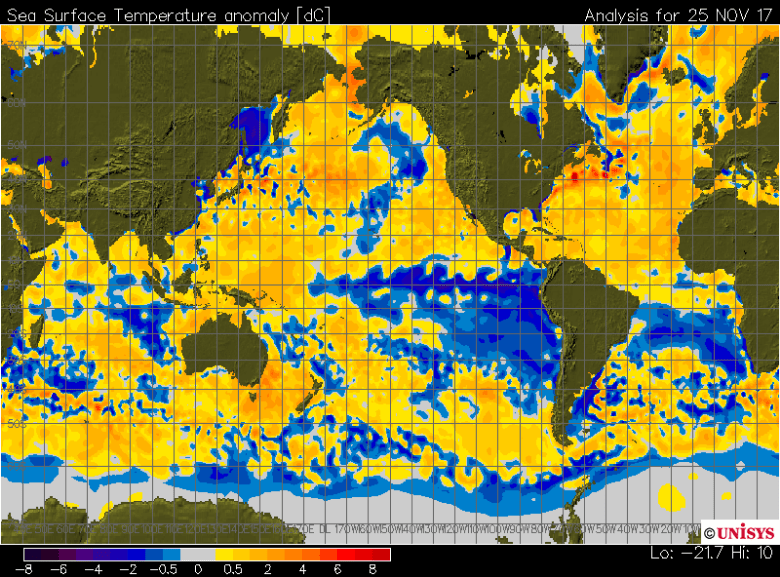

Climatologists and meteorologists try to evaluate other winters in which the atmospheric controls (or as I call them switches) may have been in similar positions as they are this year. This includes evaluating ocean temperatures.

For example, the two images below compare sea surface temperatures in 2013 to this year. Notice the pools of warm and cold water are very different, so it’s unlikely our winter will resemble that year, based on this factor.

1:

2:

Different forecasters will weight these variables very differently.

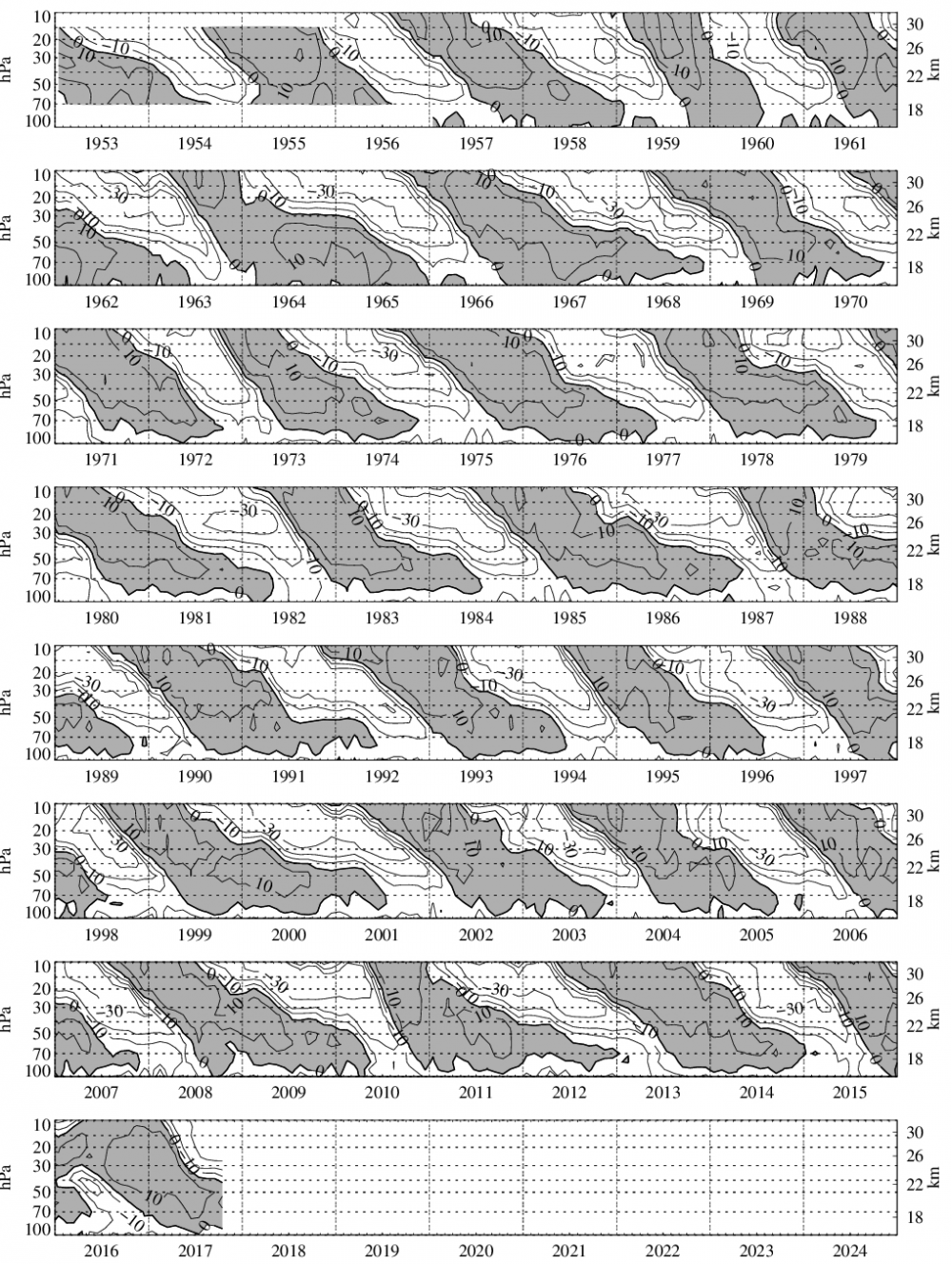

NOAA, for example, relies heavily on the El Niño/La Niña oscillation, whereas some of the folks at WeatherBELL might look closer as solar activity or the quasi-biennial oscillation (QBO). This is a quasi-periodic oscillation of high altitude winds around the equator. Interestingly, these winds oscillate between easterlies and westerlies in the tropical stratosphere, with a mean period of 28 to 29 months. There is some correlation with the easterly phase and more severe winters in North America.

Below, you can see how these winds have been switching back and forth. The gray shading is westerly winds. Remember, this is up high in the atmosphere, roughly 11 to 18 miles above the Earth. This year it looks like we are entering the easterly phase of this pattern.

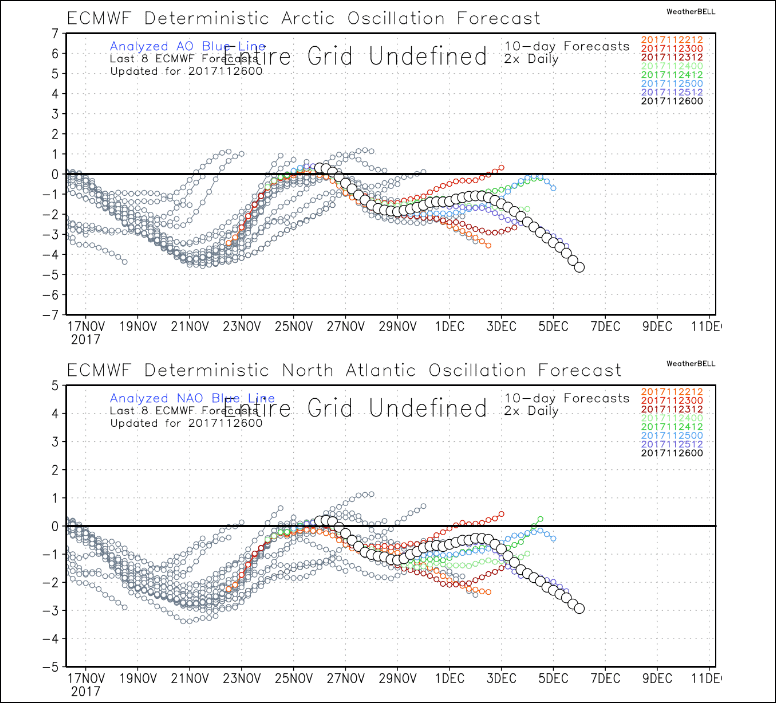

Other variables such as the Arctic Oscillation and the North American Oscillation change more frequently and bring about periods of cold and snow.

Sometimes the AO and the NAO can become stuck for longer periods of six, 10 or even 12 weeks during the winter. This is when we will often end up with snow droughts or snow blitzes. A negative AO and NAO tends to keep New England cold and stormy. There are signs each of these may turn negative within a few days of Christmas this year, bringing severe cold before the end of the year.

If this happened, then the challenge for forecasters is, does it last? Or is the cold more transient, as it was the past couple of years?

Climate Change And Winter

Meteorologists have a much better handle on seasonal forecasting than we did a decade ago. However, another important factor amid all of this is the warming planet itself.

While patterns from the 1950s can return in 2018, our planet is warmer than it was back then. Changes in snow cover, sea ice and overall ocean temperature also impact how all these variables I’ve mentioned behave. In a warmer world the QBO may do things we haven’t seen before, or ENSO may fluctuate more dramatically.

OK, What About This Winter?

You likely have noticed I haven’t made a prediction for this year’s winter yet.

Based on all the various variables out there, and the fact we turned colder in November after a warm start to fall, I am leaning toward a more typical winter, which has more cold in December than we have seen in the past couple of years.

I have been telling people to expect total snow in Boston within about 10 inches of average, and I have a slight lean toward the higher end of average this year, as opposed to under, but neither would be surprising.

Unlike a couple of years ago, in 2015-'16, when a very strong El Niño gave many forecasters, including me, high levels of confidence for a warm winter, this year my confidence is lower than average, so expect the unexpected.