Advertisement

How Record-Breaking Weather Informs Climate Change Policy

Resume

The audio atop this post contains an interview between All Things Considered host Lisa Mullins and Austin Blackmon, Boston's chief of environment and energy.

At about 2:30 a.m. Thursday, Austin Blackmon, Boston's environment chief, received word that the first nor'easter of the year was going to be a rarity, with forecasts predicting a storm that would bring about a 100-year flood. (That is to say, the storm's intense conditions had a 1 percent chance of happening in any given year.)

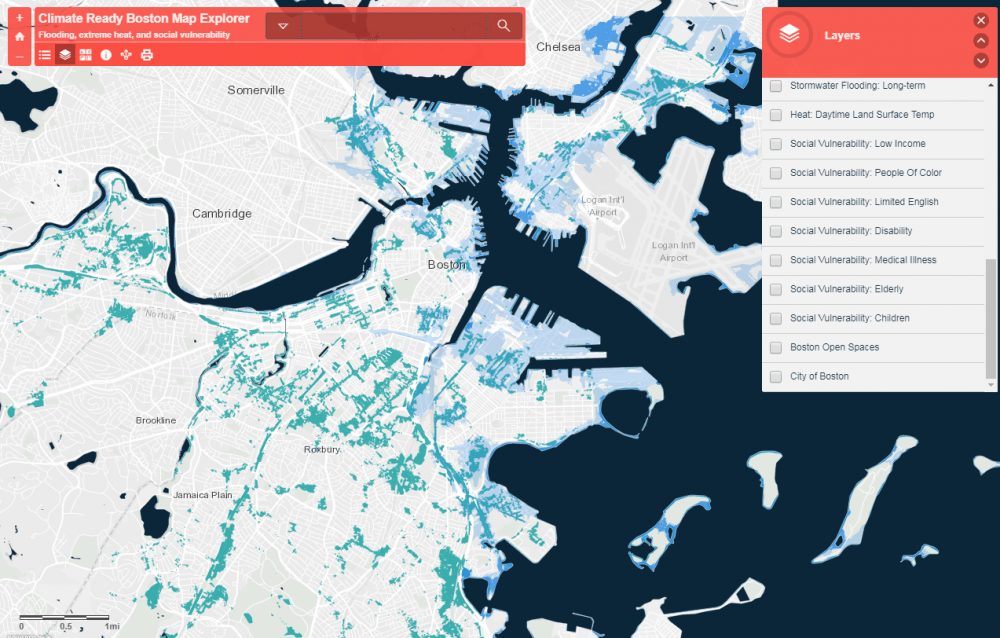

As the predictions changed, other key players in the city's government needed to know what to expect: What places were most vulnerable? What roads might become impassable?

“By getting that information out as soon as we had it, it helped us in terms of our response, and folks knowing what they were going to be facing,” he said.

As the person heading up climate change preparedness in Boston, Blackmon's job is to make sure the city has an idea of what's going to happen when extreme weather strikes.

Blackmon wasn't surprised by the amount of flooding in Boston, especially in places like Fort Point in South Boston or Suffolk Downs in East Boston.

"Shocking, but for me, not super surprising," he explained. "It’s basically what the city is going to have to deal with now, and as sea level rise continues we’ll be dealing with events like that more frequently.”

In the wake of a storm like this, planners can learn a lot what might come in the future. For one, extreme weather events can help verify what models might have only said could happen.

Major storms can also help officials learn about the operations they need to deploy to mitigate damage before, during and after a storm hits, said Nasser Brahim, a senior planner at Kleinfelder, a company hired by the city of Boston to consult on its climate plans.

“It’s a really complex decision for people who are responsible to the public and for public spending," he said, "because they have to weigh the cost of mobilizing and taking action and potentially shutting down services preemptively, with the actual likelihood that that’s going to happen.”

He said this week's storm was likely an eye-opening moment for leaders and public safety officials in Boston. In this case, damage from the storm mirrored conjectures, but estimates can't account for everything.

“Given the fact that this was a record-high tide, it’s going to test the work that we’ve done already in terms of the projections," Blackmon said. "[It] might show us some additional areas where we were vulnerable that we weren’t expecting. That’ll be instructional for us.”

Using available information about tide levels, storm intensity and sea level rise, planners pinpoint vulnerable areas.

This week's storm broke the record for the highest tide ever recorded since 1921. WBUR meteorologist David Epstein explained that happened due to the storm occurring during the highest tides of the month, the storm's own intensity and sea level rise.

"When we look forward at sea level rise," Brahim said, "in 2030, [flooding] would be almost a foot higher than we’ve experienced."

City officials will examine what they did during the storm. They'll work to figure out the entry points that led to flooded zones throughout the city, and go over how various other operations, including emergency services, went. They'll also use this information to ensure they're making the right recommendations to protect older parts of the city, while advising new developers, like GE.

Along the South Boston Waterfront, Blackmon said the recently approved development known as Seaport Square is a testament to what's being done to make sure new buildings in the city are up to the challenge of climate change.

Following the storm, WS Development reported that "the entire Seaport Square area remained high and dry," adding in a statement that the buildings are being "constructed with higher ground floor elevations and surrounding street grades that were designed to protect Seaport Square from events such as today’s storm."

Suffolk Downs, a proposed site in Boston's bid for Amazon's second headquarters, did flood, however. In Blackmon's view, Boston is growing, and many low-lying areas like this one in East Boston are sites the city must protect.

“We’re not going to be able to stop flooding in Boston," he said, "regardless of how much money, time, effort we expend. We are still going to have floods here.

"But the question is, how quickly can we get back to normal, and how can we minimize that damage that’s caused by those storms?”

With additional reporting from WBUR's Lynn Jolicoeur

This article was originally published on January 05, 2018.

This segment aired on January 5, 2018.