Advertisement

Why The Immigration Court Backlog In Mass. Is Growing Faster Than In Almost Any Other State

It's 8:30 a.m. on a recent morning in Boston's immigration court. A federal prosecutor for the Department of Homeland Security pushes a cart loaded with case files into a courtroom. She wedges the cart between a wall and a desk and heaves a pile of paperwork onto the tabletop. Another day full of master calendar hearings is about to get underway.

For an immigrant who's fighting deportation or applying for asylum, a master calendar hearing is their initial court appearance. It kick-starts the rest of their proceedings, and they usually walk out with a date for their next court appearance.

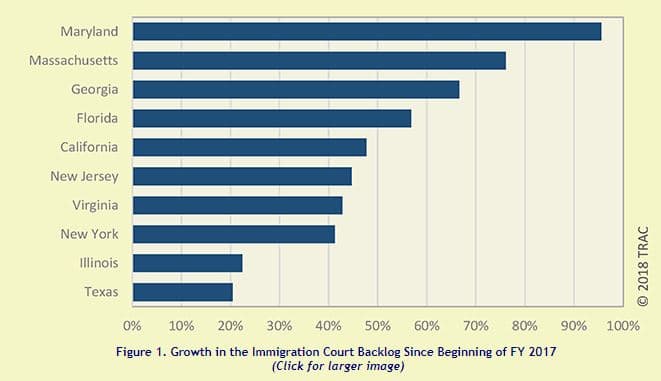

In Boston, those dates are being set further and further out thanks to the nearly 27,000 cases already pending — an increase of 76 percent since President Trump took office. It's the second-largest spike in the country.

'A Dramatic Impact'

Sarah Sherman-Stokes is a Boston-based immigration attorney and a clinical instructor at Boston University's School of Law. She says a bigger backlog can mean longer wait times.

"The growth in the immigration court backlog has a dramatic impact on our clients," she says.

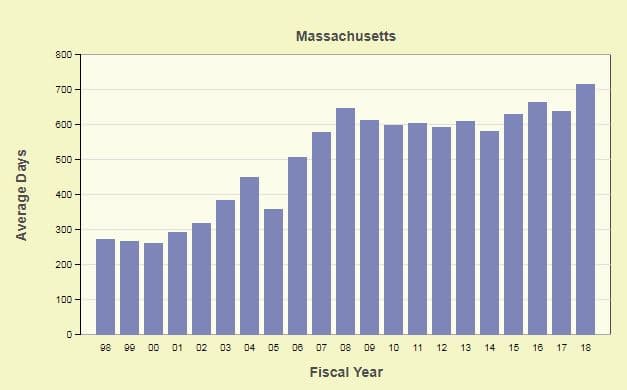

According to TRAC, a national immigration database at Syracuse University, the average wait time in Boston is around two years. That's gradually been ticking up over the last several years. Sherman-Stokes says that's a problem for many of her clients, especially those seeking asylum after experiencing tremendous amounts of trauma in their home country.

"The longer the amount of time that passes between the incident that happened and them having to retell it in a court room, in an adversarial setting, the more difficult it becomes for them to do that with accuracy," she says, "and even small inconsistencies can be the basis for an asylum denial."

In September, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions set a goal of increasing the number of immigration judges in the country by 50 percent. The thought is that new recruits will help tackle the massive case backlog that continues to grow nationally. But simply adding more judges might not be enough to put a dent in the backlog anytime soon.

Dana Leigh Marks is an immigration judge in San Francisco and the former head of the National Association of Immigration Judges.

"While there is now an almost frantic effort to increase the numbers of immigration judges, it takes a very long time to unwind a backlog," Marks says. "That's because as cases get older and remain on the docket longer, they generally become more complicated."

Advertisement

Evidence becomes stale, witnesses are hard to locate and individual circumstances change. For instance, maybe so much time has passed that a person is now eligible for a different status than they originally applied for. All of this, Marks says, means the longer a case sits on a docket, the longer it can take to adjudicate.

"While there is now an almost frantic effort to increase the numbers of immigration judges, it takes a very long time to unwind a backlog."

Dana Leigh Marks, an immigration judge in San Francisco

And there's another issue to consider, she says, as more first-time immigration judges come on board.

"In all fairness to someone new coming in, they're entitled to have a learning curve and to take time to do it right, and with repetition they will do it right and faster," Marks says. "But I would assume that has an impact — again, just one piece of a multi-faceted puzzle."

This is especially relevant in Boston, where four of the eight immigration judges were appointed within the last two and a half years.

Three of those four new judges in Boston also previously worked in the city as attorneys for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Susan Church, an immigration attorney in Cambridge, says that in particular matters when looking at the Boston immigration court's backlog. Former government prosecutors turned immigration judges must recuse themselves from any cases they touched as prosecutors.

"Where three of the last four hires have been former prosecutors, these judges have to decline jurisdiction over any case that they have handled or worked on while they were prosecutors in that office," says Church. "So it really doesn't help the backlog because then that case has to go to a different judge and start the process all over again."

The rules around recusal are the same for former private immigration attorneys who become judges. Those cases then end up on another judge's docket, and the immigrant's court case starts all over again.

It's difficult to know how often judges recuse themselves on these grounds. The Executive Office for Immigration Review, the oversight agency for the country's immigration courts, doesn't track recusals.

Marks says the backlog reflects a fundamental imbalance in the resources allocated to ICE prosecutions versus the resources allocated to strengthening the courts.

Until the court system grows commensurate with the enforcement system, she says, backlogs will likely continue to rise, and immigration judges will keep playing catch up — in Boston and across the country.

This segment aired on October 31, 2018.