Advertisement

Review

Two renowned orchestras return to Boston Symphony Hall

With the return to Symphony Hall of two of the world’s leading orchestras (thanks to the Celebrity Series of Boston) in sold-out concerts, the pandemic—or at least the scare of the pandemic—seems to be officially over. It’s been three years since superstar conductor Gustavo Dudamel was last here with the Los Angeles Philharmonic (the major work on that program was Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”), and twice as long since the Berlin Philharmonic, under Sir Simon Rattle, was last here (with a thrilling program contrasting Pierre Boulez’s scintillating “Éclat” with Mahler’s phantasmagorical Symphony No. 7).

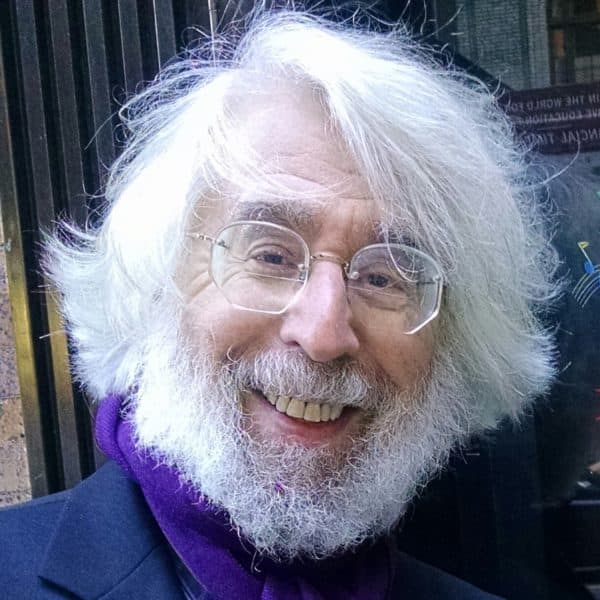

Now, within a period of three weeks, both of these orchestras were back for a brief visit, the LA Phil with Dudamel, and the Berlin Phil with its new music director in his first Boston appearance, the Russian-Jewish artistic director and chief conductor Kirill Petrenko, the Berlin Phil’s first Jewish music director in its distinguished and complicated 140-year history.

Comparisons between the two visiting orchestras are inevitable, as are comparisons between these visiting orchestras and Symphony Hall’s resident orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The Berlin Philharmonic is often regarded as “the world’s greatest orchestra.” It’s not hard to hear why. The 43-year-old American composer Andrew Norman’s “Unstuck” (composed in 2008, inspired by the shifting time elements of Kurt Vonnegut’s “Slaughterhouse Five”), is a short piece for full orchestra that requires each player to turn on a dime, from wild percussion to ineffable high cellos with staccato bow taps to hunting horns and suggestive—or comically deflating—string slides. I was reminded of the famous line from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” 100 years old last month: “These fragments I have shored against my ruins.” Both the quickness of these sudden turns and the depth and beauty of the sound, from each player without exception, was nothing short of astonishing. Even the violence sounded beautiful. It was a perfect piece to begin with, to show off the orchestra’s strengths.

Petrenko has a light touch. At times his baton hardly moves at all. But you can see the music racing through his whole body. He shivers with it. He’s not a dancer on the podium, but every gesture, every part of him projects the music.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic is in wonderful shape right now and plays with a comparable brilliance if not an equal depth. Like the Berliners, these players are impressively flexible, giving Dudamel everything he asks for from moment to moment. And Dudamel too seems to be inhabited by the music. His breathtaking Mahler First Symphony, one of the greatest first symphonies ever composed, a long and complex semi-autobiographical flashback of a symphony—how many times have I heard it?—had me on the edge of my seat, making every transition count for its entire length, from spring’s awakening to ironic death march (a minor-key “Frère Jacques” on the double bass). I was moved, excited, and completely riveted, and the audience rose as one for a prolonged—and deserved—standing ovation.

I listened on the radio to Andris Nelsons lead the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 and found the playing extremely beautiful but—an old problem—Nelsons’s shaping of the phrases felt a bit stiff and the whole piece lacked mystery. The problematical love theme seemed too fast and a bit hysterical. There was never a moment in the LA Mahler performance in which I felt that Dudamel didn’t understand what the music was actually about.

Both of these concerts had several important things in common. One was that each began with a contemporary piece—recent pieces that stand a good chance of remaining in the repertoire. Dudamel, who is Venezuelan, makes a point of featuring music from Latin America. He commissioned an ambitious new violin concerto, “Altar de cuerda” (“String altar”—the seventh in her series of “altar” pieces), by the distinguished Mexican composer Gabriela Ortiz (who is rarely heard in these parts).

This was its Boston premiere. There are some memorable orchestral effects, including at the beginning and end of the slow movement when all the wind players are playing otherworldly tuned crystal glasses. The concerto also introduced to Boston a phenomenal 19-year-old Spanish violinist, Maria Dueñas. The long violin soliloquies Ortiz gave her conveyed both real and nuanced feeling and great rhythmic vitality. The audience couldn’t get enough of her. Her exquisite encore was an arrangement of the tender Francisco Tárregas guitar piece, “Recuerdos de la Alhambra."

At the end of the concert, Dudamel gave us a hilarious encore, Johann Strauss Jr.’s famous “Tritsch-Tratsch Polka” in a new arrangement by Venezuelan composer Paul Desenne called “Triqui Traqui,” in which the Austrian polka kept veering off into a Latin-American jota.

The Berlin Philharmonic had an equally impressive violin soloist—Noah Bendix-Balgley, one of the orchestra’s two principle concertmasters—who may have had an even harder time having to make interesting Mozart’s very first violin concerto (composed at the age of seventeen). With his supple tone and attentive tenderness, Bendix-Balgley almost succeeded. The concerto shows plenty of confidence, while it lacks the nuances, the heavenly slow movements, or the originality of Mozart’s last three violin concertos, though they were all composed around the same time.

If the Norman piece showed off the whole orchestra, the Mozart showed off the refinement of the Berlin strings. I was touched by Bendix Balgley’s visible acknowledgment of his fellow violinists. “That’s probably the best performance of that concerto we’ll ever hear,” I overheard someone say during the intermission. “Now we don’t have to hear it again.”

Bendix-Balgley’s biographical note in the program tells us that he is a renowned performer and composer of klezmer music, and his gift to us was an encore of two klezmer tunes, the lamenting “Yismekhu” and a lively dance, “Ot Azoy,” in which a couple of times the violinist actually shouted out the Yiddish title, which means something like “Just like this!” The audience gobbled it up.

Ticket prices for these concerts ranged from being free for some students and community members to an expensive high of $180. Dudamel and Mahler are well-known and popular commodities. But the Berlin Philharmonic program was decidedly not oriented for box-office appeal: a relatively little known contemporary piece; a minor Mozart concerto, and Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s rarely heard Symphony in F-sharp Major (1954), for which Berlin’s new music director happens to be a major advocate. Yet Symphony Hall, with more than 2600 seats, was virtually sold out for both events.

Most people know Korngold from his memorable film scores: “The Adventures of Robin Hood” and “Anthony Adverse” (both of which won him Oscars) as well as the Bette Davis/Errol Flynn “Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex” and the Ronald Reagan “King’s Row” (themes from both of which appear in the Symphony). His ambitious early opera, “Die tote Stadt” (The Dead City), includes one of the most gorgeous arias in the soprano repertoire, “Mariettaa’s Lied” (the complete opera was presented here in concert by Odyssey Opera in 2014). Nothing is quite so ravishing in the Symphony which alternates two lively, vigorous movements (one an unstoppable tarantella) with two rapturous ones, each with its share of chiaroscuro. It’s as long as a Mahler symphony, but I didn’t hear much that was truly searching or developmental, which is what made it sound more like four long movements of high-end movie music. Still, I was glad to hear it, especially played on such an exalted level and with such obvious passion.

The other fascinating element that these orchestras have in common, and one to which I wish Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra would return. is that both Dudamel and Petrenko divide the first and second violin sections antiphonally, instead of grouping all the violins on one side of the stage, as Nelsons now does (rejecting James Levine’s seating plan of having the first and second violins on opposite sides of the stage).

Though it’s harder to coordinate, this seating plan has many benefits. One is that you can hear the difference between the parts written for the first and second violins, a difference sometimes considerable and even magical. It’s like listening in stereo. And in a warm acoustic like Symphony Hall, the lumping together of the two violin sections thickens, even blurs rather than opens up the texture. So what a pleasure to hear in both the Mahler, in which the scoring is more spacious, and in the Korngold, in which the scoring is more full-bodied, an airier, more open quality in which each instrument and each section has its own clearly audible identity.