Advertisement

Review

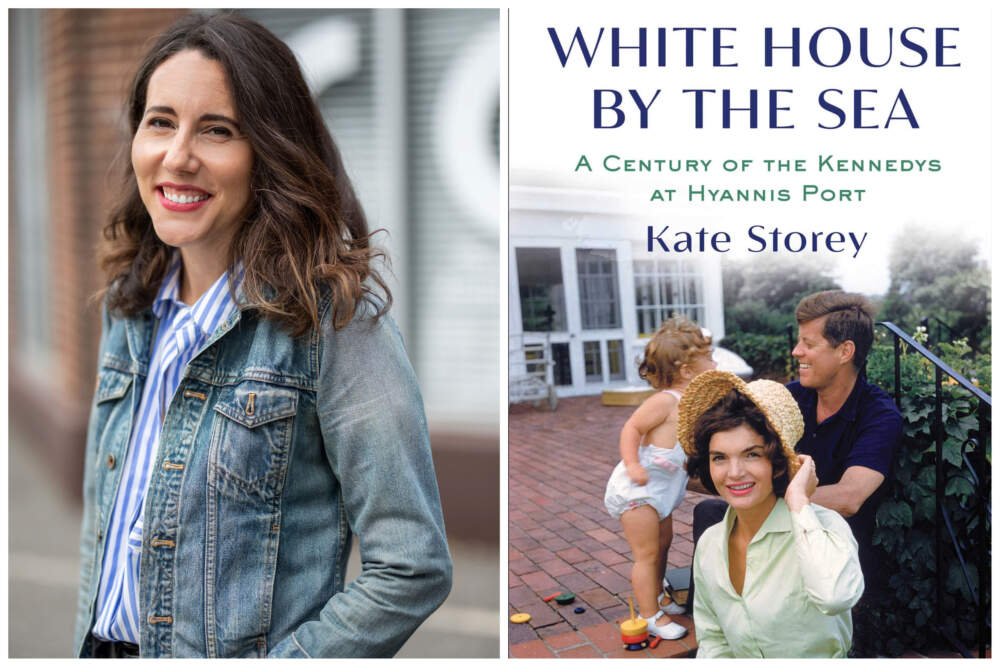

New book 'White House by the Sea' covers a century of Kennedys on the Cape

Maya Angelou once wrote, “The ache for home lives in all of us, the safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.” That sentiment could apply to “White House by the Sea: A Century of the Kennedys at Hyannis Port,” Kate Storey’s thoughtful and astute history of the Kennedys and their famous Cape Cod home.

With countless books available on this most famous of political families, it would seem there would be little new to write. But Kate Storey has found a genuinely fresh historical angle. Based on interviews with family members, Hyannis Port friends, neighbors, and townspeople, as well as previously published works on the Kennedys, “White House by the Sea” shows how the homes that comprise the Hyannis Port compound shaped this family’s character: amplifying good times and sustaining them through tragedies. As depicted in this book, Hyannis Port formed the deep center of this family’s universe: its home base and its sanctuary.

The Hyannis Port compound began with one large house, three acres of coastal land and a private beach. The house, at 50 Marchant Ave., was situated at the end of the short dead-end street. It was built in 1904 and for years known as the Malcolm Cottage (for its owner Beulah Malcolm). Joseph P. Kennedy bought it in 1928 for his growing family. At that point, Joe and Rose had eight children (Joe Jr., the oldest, was born in 1915, and Ted, the ninth and youngest, would be born in 1932).

Always one to live large, Joe immediately expanded the house “to twenty-one rooms, including twelve bedrooms, a steam room, a theater in the basement.” Joe, who was then in the movie business, had the first home theater in New England.

By the time the Kennedys moved in, Hyannis Port already had its share of wealthy summer residents: old-money families proud to be low-profile, not like the ostentatious crowd at Newport or Bar Harbor. The kids made fast friends with their neighbors, although the friends’ parents were less than thrilled about the boisterous Kennedys, especially Joe, who drove a “loud, flashy car” and “seemed to like being noticed.”

With an abundance of anecdotes, Storey highlights how “things just seemed to make the most sense to the Kennedy kids” at Hyannis Port. This was where the kids, even as they grew to adulthood, returned as often as they could. The same would be true of their own children. The pull was so strong that when Joe was Ambassador to the United Kingdom, the family returned home to spend the summer of 1938 at the Cape. As students during World War II, Bobby and Ted would leave their boarding schools to spend weekends at the closed-up compound, getting solace from their home even when they were the only ones there. During the 1990s, JFK Jr. would craft his work schedule so he could spend as much time as possible in Hyannis Port with his cousins and friends.

The clannish nature of the family was apparent early on. Rose liked to send the younger kids to camp in New Hampshire for part of each summer, but they all just wanted to be with each other. Between their home and a farm in nearby Osterville where they kept horses, it was better than any official camp: sailing, swimming, tennis, horseback riding and a neighborhood of friends.

Against the backdrop of many summers and autumns (the family would also spend Thanksgiving in Hyannis Port), Storey sketches familiar portraits of the different family members (Joe Jr., the frequent bully to his younger siblings; Jack, clever and puckish; Eunice, fiercely competitive but also the most caring to cognitively-impaired Rosemary). “White House by the Sea” also offers some lesser-known lore, like Rose having a hut built for herself at their beach as a little refuge from all the activity at the Big House.

Of course, we wouldn’t know about Hyannis Port if the Kennedys themselves hadn’t been so natural about publicity. Storey recounts, in engaging detail, how the pivotal July 20, 1953 Life magazine cover feature on JFK and his young fiancée Jackie came about. Photos of the glamorous couple in casual clothes, sailing and relaxing at that huge home overlooking the ocean did more to spin a fairy tale than pictures of any lavish gala could have done.

That’s a large part of the Hyannis Port myth that Storey tells: larger-than-life people doing regular things. With her accounts of the younger generation, the one that lost fathers and uncles to assassinations in the 1960s, Storey shows how getting a glimpse behind the curtain can be enthralling for the audience but brutal for those growing up and into their teenage years under a constant spotlight.

JFK’s presidency changed the town of Hyannis and changed the tenor of the family sanctuary. From that 1960 election night to the present day, Hyannis Port would be overrun by photographers, newspaper reporters, TV crews and even boat tours that would come as close as legally possible to the family’s beach. Through the decades, the Kennedy compound would also be a magnet for countless celebrity guests.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the siblings, now with their own families, bought or rented houses near the Big House to create some distance in all that extended-family togetherness. As Storey notes, the other Kennedy mothers wanted to keep their kids a little apart from Ethel and Bobby’s kids, as there was a “wildness” to them (which would get more extreme as the years went on).

When she was newly First Lady, Jackie was aware of how the cousins were “so fixated on all the new attention” bestowed on Caroline and John. In an interview with Storey, Mark Shriver, son of Eunice and Sargent, remembers how the cousins were “very, very competitive” and that photographers’ singular obsession with John and Caroline did cause some strain. To that point, it’s significant that “White House by the Sea” includes photos of many family members in different eras, but the cover photo is of JFK, Jackie, and a very young Caroline.

Storey keeps the narrative smartly focused by prioritizing location over a broad history. If something did not occur at Hyannis Port (like Ted’s 1991 misadventures in Palm Beach), it’s only briefly noted for context in a particular time period.

The Kennedy compound was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1972, this private residence holding as much history as some government buildings. Throughout “White House by the Sea,” Storey subtly underscores its dual nature, such as when, in 1956, Jack announced to his family that he would run for president, and four years later, the house was the communications center on election night. Or that it was the place Jackie and her children came for solace after Jack was assassinated, and where her famous “Camelot” interview with Theodore White took place.

There are still Kennedys in Hyannis Port, including some of the adult children of Eunice and Sargent Shriver, Ethel and Robert Kennedy, and Ted and Joan Kennedy, and Storey provides tales of the next generations (Taylor Swift even makes an appearance — she dated Conor Kennedy in 2012).

And still, there’s a bittersweet nostalgia that moves through some chapters like a light mist off Nantucket Sound — of a long-ago, tightknit world of family Sunday dinners and days filled with games in a coastal playground that, once upon a time, could close out the rest of the world.