Advertisement

The Childhood Friendship Dodgers Legend Carl Erskine Never Forgot

This is the story of Johnny and Carl.

Carl and Johnny were friends growing up in Anderson, Indiana — about halfway between Indianapolis and Muncie.

Their story begins at the tail end of the Great Depression. No one in their neighborhood had much money. Take Johnny's family.

"Couldn't afford a basketball, so we took an old sock and put rags in it, then we put a rock in it, then put rags on top of it to use as a basketball," he says. "You couldn't bounce the rock, so we'd go along and holler dribble, dribble, dribble, and when you stopped saying dribble, you had to shoot the ball. So that was our dribble, right there."

Johnny met Carl when they were in the fourth grade, and Johnny's access to sporting equipment improved a bit.

"That was the first time I had the chance to play basketball with a real basketball," he says.

"Johnny lived on 13th street and just a block or so over on 14th is where I lived," says Carl . "So we walked to school together, but we spent more time playing any sport that you could name in the streets around our neighborhood."

"Any day that ended in Y, we usually got out there and played basketball, no matter how cold it was," Johnny says. "It was dirt, there were some ruts in the alley, when you bounced the ball you had to learn how to control it."

"But we could dribble both hands, and if you could dribble on that, buddy, you could dribble anyplace," Carl says.

A friendship between two neighborhood kids wouldn't be all that unusual, but these kids teamed up in the late 1930s. And Carl is white. And Johnny is black.

"Our YMCA did not accommodate black memberships," Carl says. "But the city parks had a swimming pool and there was... one day a week, at least, where blacks citizens of Anderson could swim. So Johnny couldn't go with me, so sometimes I think we used to go with Johnny, but you know, we were kids. Johnny and I look at each other, there was no color barrier there. We were buddies and Hazelwood was a mixed neighborhood. Nobody had much wealth in that neighborhood. I hate to say we were all poor, but the common bond was [that] economically we were all struggling a little bit, and that's why racism was not very evident."

Advertisement

The town’s rules required Johnny and Carl to play on separate summer recreation baseball teams, but during the school year they were teammates — and together they helped their elementary school to a city championship.

Carl knew a place would be waiting for him on the high school basketball team. Johnny was told that the same might not be true for him.

"[It] wasn't one of the high school coaches, it was a guy that was affiliated with basketball in the city. He came and told me, Johnny, you know something, in order for you to make the basketball team, you gotta be twice as good as any white kid on the team," he says. "That next year as a sixth grader in grade school, I'd scored 250 points and the next player had scored 99. So I took the clipping out of the paper, the only clipping I ever cut out of the paper the whole time I played ball, and I asked this individual, do you think that I'm good enough now to play high school ball."

Carl and Johnny would both go on to play high school basketball, though Johnny was the real star. He led Anderson high to the state title in 1946, scoring 30 of the team's 67 points during the championship game.

"It was tough to get the ball in to Johnny because they'd drop back on him and double team him and you couldn't hardly get a pass into the center," Carl says. "But the coach said, 'Put it on the backboard. You make a lot of your shots, but the ones you don't make, Johnny'll be all over it.' So, one of the ways to get the ball to Johnny was to shoot."

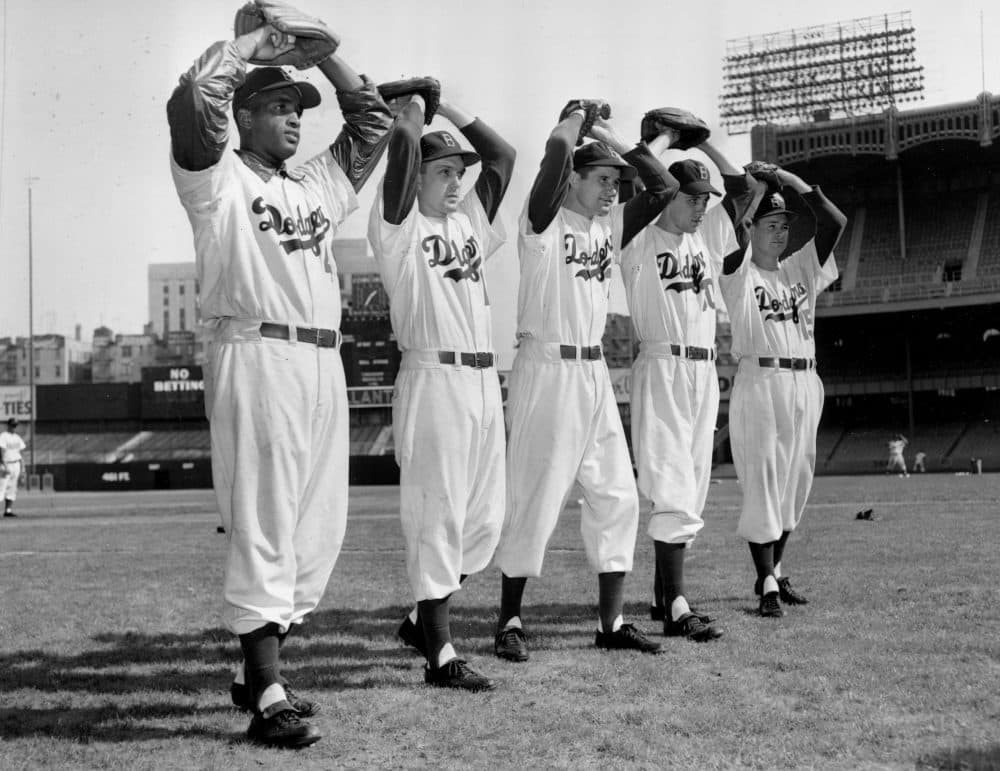

After high school, Carl Erskine would move to Brooklyn, where Dodgers fans began calling him Oisk. He'd go on to throw two no hitters and appear in 11 World Series games.

"He said, 'Well hows come the race thing doesn't bother you?' I said, 'I can give you two words: Johnny Wilson.'"

Carl Erskine

In 1947, the Dodgers had integrated Major League Baseball. When Carl Erskine joined the team in 1949, he had no trouble embracing his new teammate.

"When Jackie Robinson — I played with Jackie nine seasons — when he came to me one day early in our career and he thanked me for stopping outside the clubhouse, where all the players used to meet, and talk with Rachel, his wife, and little Jackie, his son," Erskine says. "I stopped out there, just a natural thing. I stopped to talk to Rachel. And the fans could all see through this gated area. Well Jackie came to me the next day and thanked me for doing that. I said, 'Well, come on, Jackie. Look, if I pitch a good ballgame, you can come over and [congratulate me]--but not for that. That's just a natural thing.' He said, 'Well how come the race thing doesn't bother you?' I said, 'I can give you two words: Johnny Wilson.'"

Johnny Wilson's path after high school was considerably less smooth. He had been named the best high school basketball player in Indiana, but the coach at Indiana University said he wasn't good enough to play there. Instead, Wilson went to Anderson College, where he led the state in scoring. When the NBA showed no interest, Wilson played for the Harlem Globetrotters. But baseball was Wilson's favorite sport, and one day, the St. Louis Cardinals staged a camp in Anderson.

"And in that camp in the two days I had 11 times at bat, I had four home runs, three triples and two doubles," Wilson says. "And they didn't even ask me my name. People say, 'Hey, they prevented you from making the Majors, prevented you from playing in the NBA in basketball.' No one prevented me from making it, they just prevented me from making a tryout."

"In fairness, the racial thing, I've never heard Johnny say a bitter word," Erskine says. "He has handled things. I put it in simple terms: he beat all the odds."

Carl Erskine, of the two Major League no-hitters and 11 World Series appearances, is so impressed with his friend, who went on to teach high school in Anderson, that over the past few years he's helped to raise $60,000 for a nine-foot bronze statue of Johnny Wilson in his Harlem Globetrotters uniform. The statue was unveiled at Anderson High School in May.

"The artist says it's not a statue," Erskine says. "Anyone can make a statue. This is a sculpture. So it raises it above the ordinary, and that's what Johnny did himself."

Lest you be concerned that Carl Erskine, of the two Major League no-hitters and 11 World Series appearances, hasn’t been appropriately celebrated in Anderson, Indiana, worry not. Erskine has his own statue — I mean sculpture — in front of a building bearing his name at St. John's Hospital.

"He was a little peeved at me because mine's nine foot tall, his is about six foot," Wilson says. "When we were in grade school, in the fifth grade on that championship grade school team, he was the biggest kid. He was the center. But since then I've outgrowed him, I'm about 4 inches taller than he is now, so they had to put my sculpture bigger than Carl."

Of course “bigger” isn’t the point. The point isn’t statues either. Carl Erskine’s desire to commemorate the achievements and the determination of his friend is part of the point, and the rest of it is the friendship that began on the uneven basketball court in that dirt alley in Anderson. There, neither the white kid who’d go on to pitch for the Dodgers nor the black kid who starred at basketball and become a school teacher saw color at all.

This segment aired on July 16, 2016.