Advertisement

'The Banana-Leaf Ball' Shows How 'Play Can Change The World'

Resume

Want more Only A Game? Follow along on Facebook and Twitter.

This is a story that, like a lot of stories, begins with a journey. When the journey began almost 25 years ago, the fellow who made it was perhaps 10 — he’s not sure.

Benjamin Nzobonankira is a survivor, and in order to survive, he had to take that journey. It began in Burundi, where Benjamin had been enjoying a childhood he describes as "normal."

He told me his family was "not rich, not poor." And then that family and many, many other families were suddenly confronted with civil war.

"That was 1993, when the first democratic president was killed," Benjamin says. "Our situation became very tense, and we were obliged to flee the country."

Benjamin’s journey led him to a refugee camp in Rwanda. Within a few months, the genocide that would tear that country apart made living in the camps more dangerous than living in Burundi had been. The journey continued. The refugees survived by eating leaves off the trees.

Benjamin made it to the Democratic Republic of Congo, briefly. There his mother and youngest sister died in the forest when militias chased them out of the country. Benjamin eventually reached Tanzania. By then he was alone, having been separated from the remaining members of his family.

The politics and conflicts at each stop must have been impossibly confusing to children like Benjamin. But he understood immediately — and every day — that he was hungry.

"In my home country, I didn’t spend a day without having a meal," he says. "Such as breakfast, lunch or dinner. It was very strange. Strange people there, strange conditions. Actually, I come to realize that, can life — will life be like this?"

Hunger wasn’t the only problem. Children like Benjamin were often bullied into joining militias. Some of them did that. According to Benjamin, others spent their days sleeping and crying.

An Opportunity For Play

That’s how things might have remained, if it hadn’t been for a champion speed skater from Norway named Johann Koss. Before the 1994 Winter Olympics in his home country, Norway’s Olympic organizing committee asked Koss to travel to Eritrea to represent a relief organization called Olympic Aid.

"And when I got there, I met a group of boys, and one was very popular, and I asked, “Why are you so popular?'" Koss says. "And he looked at me and said, 'Can’t you see? It’s the long sleeves.'

"Well, then he took off his shirt, rolled it together, and the sleeves made a knot. And that became the ball, and that’s how they played soccer in the streets of the slums of Asmara, which is in Eritrea, where I was headed. And I — I’m, like, 'Have you ever had a ball? Have you ever had a team? A coach?' And they looked at me like I came from a different planet."

On the planet Johann Koss called home, superb athletes trained for years in order to dazzle millions of television viewers. Koss says the trip to Eritrea helped him to put his training in a context he’d never before considered.

"When you train so much and so hard, it’s very hard to find that deeper motivation," Koss says, "and if you can find a purpose for what you’re doing, broader than yourself, which was, for me, to provide those kids with sport opportunity, that led me to become a much better athlete, actually."

Motivated in part by the purpose he’d discovered in Eritrea, Koss turned in a spectacular performance at the Winter Games.

He won three gold medals, setting a new world record in each of his races.

At a press conference after his second win, Koss announced that he would donate all of the bonuses he’d earned from the Olympic committee and his sponsors to Olympic Aid. He challenged the Norwegian people to donate as well.

And he must have been convincing. Some of the journalists in the room opened their wallets and handed him money on the spot.

And then Koss went back to Africa.

"As I had promised, I collected 13 tons of sport equipment, spread all around Norway," he says. "And, listen, I was 25. I had no idea about international development, but I was very stubborn. And I was flying down to Eritrea, and then the newspaper in Norway wrote that, you know, 'Koss is bringing soccer balls to starving children. What an idiot!'

"And I’m not used to being called an idiot, certainly not at that time. But when I arrived, I have never in my life been met by so many people. I mean, there was more than 100,000 people in the street of Asmara. They had Norwegian and Eritrean flags. They put me on a bike. We were riding through the streets. I got up to the president’s palace, and I met with him, and I said to him, 'You know, I’m bringing soccer balls — it might have been a mistake.' Because he, himself, had called for food. And then he said, looked at me and said, 'You know, this is the first time we feel like human beings. Something more than just being kept alive.'"

'You Have To Love Each Other ... In That Way You Become Champion'

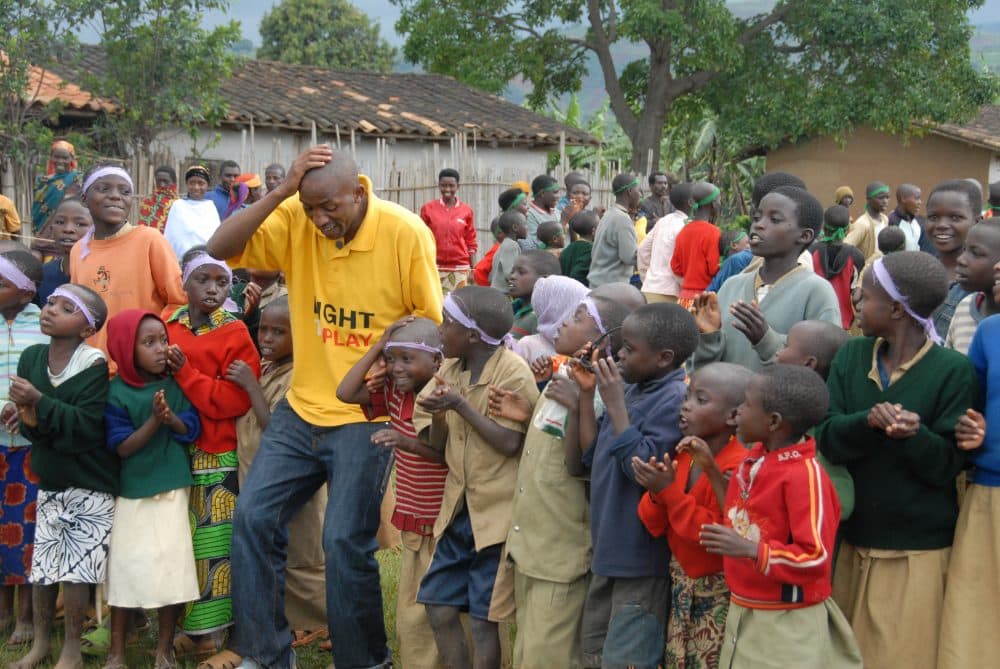

Soccer balls in Eritrea were just the beginning, and Koss soon discovered that the children in the refugee camps had even less than the child in the street in Asmara with the long-sleeved shirt. He founded the organization Right To Play to bring sports to refugee camps, including the camp at Lukole, where Benjamin had settled. Benjamin was kicking around a soccer ball made of banana leaves and twine when the coaches arrived.

"They were driving the truck with the big megaphones and say, 'Come to the field,'" Koss says. "And many times there were not even fields. They had to break ground and make that happen first, you know. People say, you know, sometimes when you do these programs, 'Oh, when you're going to see the effect, it's going to be taking, you know, months and years before you see any impact on that.' You know, and then, after three weeks, we had, like, the whole camp lined up."

"When they come and play, things changed," Benjamin says. "They become very, very excited and try a bit to forget about the bad experiences they went through."

"When people read this kind of book, they can really experience how, with play, everything can be possible."

Benjamin Nzobonankira

Benjamin remembers what the coaches said to him as they helped him learn to play.

"You have to love each other, even those who, maybe, you fled. You have to love them. And then, in that way, you become champion."

In the camp, Benjamin had plenty of opportunity to try putting that advice into practice. The bullying came with a hard, sometimes fatal edge. But playing soccer with bullies taught Benjamin that they could work together, and, perhaps more significantly, playing together taught many of these children who had lost so much that they were not so different from each other. It would turn out to be a lesson with appeal beyond the borders of the camp. A children’s book author named Katie Smith Milway would demonstrate that.

'A Welcoming Spirit'

For her book "The Banana-Leaf Ball," Milway created a little boy named Deo, a boy in a camp called Lukole in northwest Tanzania, who tries to make a ball out of banana leaves and twine, only to see his meager materials stolen by a bully named Remy. When the coach modeled on one of Johann Koss’s recruits arrives in the village, the children learn to be teammates. Together, they win a game.

Milway says she was "on the prowl" for a good story about social and emotional learning when she was reminded of the program Johann Koss had been running in refugee camps.

"And I thought, 'OK, I've got to call this guy,'" she says. "So I called him up, and I said, 'Do you have a good story of the power of play?' And he said, 'Oh, you've got to read the speech of one of my staff members in Burundi.' That's how I got to know Benjamin's story."

The challenge for Milway was turning a journey that had included the loss of family members and the death of innocents into a tale for children.

"I hoped to write a story that would, actually, resonate with kids in any playground, anywhere. Because playgrounds are not always welcoming," Milway says. "You know, the bully might be a militia recruiter, as in the case of Benjamin, but it might just be — it might be a gang member in an urban school, and it also just might be someone who’s mean."

Benjamin has no problem with Milway’s adaptation of his story. And he doesn’t mind the name change.

"Ah, Deo is Benjamin, actually," he says, laughing. "It's no different. Deo, Benjamin, just the same. It can be someone else. Benjamin, Deo, or Nick, Kathy, or someone else. It’s OK."

'With Play, Everything Can Be Possible'

Actually, it’s a lot better than "OK." It’s a powerful story. And in telling it, even though the story is for kids, Milway hasn’t pulled all her punches.

"You say at the end of the book — there’s a section called 'A Real Deo,'" I say. "It begins, and I’m quoting, 'Today almost 60 million people are refugees. Men, women and children who’ve had to leave their homes because of war, disaster.' Um, that’s in the book. What do you intend for children to make of that news?"

"Oh, well, first of all, it’s good for them to realize that the experience of children around the world is very different, and I think — I hope — kids who read the book develop a lot of empathy for kids in need," Milway says. "I hope that translates into a welcoming spirit for people of political asylum, a welcoming spirit for refugees that need a new home and a new start. But I also hope it helps kids find themselves, no matter what playground they play on, and think about that kid that maybe they don’t like so much and try to learn their story."

It might seem like a lot of hope to hang on a children’s book, but maybe not. At least one reader has lots of confidence that the message in "The Banana-Leaf Ball" will resonate with kids, maybe even inspire them.

"I thought that I could not become someone," Benjamin says, "but I actually come to realize that, finally, Benjamin — his story is somehow interesting. And I’m very grateful to Kate. She did a very interesting work. Especially when people read this kind of book, they can really experience how, with play, everything can be possible."

Benjamin became a coach for Right To Play and, more recently, now back in Burundi, he has founded an organization of his own to bring "play" to kids who need it. Benjamin’s work is driven by his determination to help at least some of the estimated 28 million of the world’s children classified as "displaced." The man who traveled as a child from Burundi to Rwanda to Congo to Tanzania knows "displaced." And he knows "need" beyond food and shelter.

This segment aired on May 27, 2017.