Advertisement

Tour De France Cheating Started With The Race's First Champion

Resume

Crime does not pay. Unless it does, right?

“Crime paid to a certain extent for Maurice Garin, yeah,” historian Peter Cossins says. “Although he’s not well-remembered for it, I suppose.”

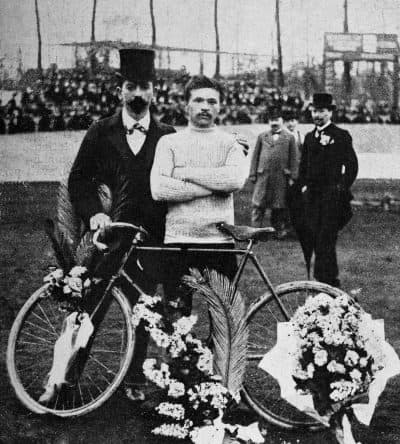

If Cossins’ supposition regarding Maurice Garin, winner of the first Tour de France, is correct, perhaps comparing Garin, who died 60 years ago, with a more contemporary winner will help establish his significance.

“Lance Armstrong was a modern day Maurice Garin," Cossins says. "That’s what Maurice Garin was like. He intimidated everybody. He wanted everybody to do things in the way that he saw was fit. He wasn’t subtle about what he was doing at all.”

To say Garin wasn’t subtle is a spectacular understatement, as you’ll see very shortly.

Young Garin And A Wheel Of Cheese

But let’s begin where Maurice Garin began, as one of 10 children in an impoverished household high in the mountains near the border between Italy and France. He was small when he was born in 1871. He stayed small, which, his Mom and Dad figured, was an advantage with regard to at least one line of work.

"His parents smuggled him — or smugglers smuggled him — out of that area and into northern France, so that he could work as a chimney sweep," Cossins says. "And, apparently, the story is that his parents received a big piece of cheese for this as a down payment."

"Yeah, you can have the boy ... but only if you give me that wheel of cheese."

In any case, when he wasn’t up the chimney, young Garin took to bicycle-riding. Actually, Peter Cossins thinks this happened when Garin was working in factories in northeast France. Lots of workers made deliveries on bikes.

‘Better Off Cheating’

At some point before 1890, as the story has it, Garin tried to enter a race meant only for professionals. Denied the opportunity, he waited until the pros had started, then raced after them and passed them all. He won the race. Then the organizers refused to give him the 150-franc prize. That may have been when Garin decided he’d be better off cheating.

In 1903, the Tour de France came into being. Unlike the point-to-point races that had come before it, the Tour would be a stage race. It would take 19 days to complete. And the winner would go home rich.

“The prize that was on offer was 3,000 francs to the winner,” Cossins says. “The average daily wage for a manual worker was about five francs a day at that time. So 3,000 francs — the possibility of winning 3,000 francs for three weeks’ work — was a huge amount of money. Riches beyond any of them could have dreamed of.”

The competition — at least at the top of the field — was fierce. Peter Cossins figures there were perhaps 10 legitimate pro riders at the starting line. The remaining 40 or so hopefuls were butchers, bakers and the odd candlestick maker. The bicycles were heavy and cumbersome. Few, if any, had reliable brakes. Their tires punctured easily. The roads weren’t paved.

None of this discouraged Maurice Garin, who was serious at the start, just outside Paris, and got more serious as the race went on. Teams were not allowed. Garin didn’t care. He rode with a group called “La Française,” and he expected loyalty from each member of that team. Sorry … group. No teams.

"There were riders throwing tacks down, nails and other stuff on the roads, so that the rivals punctured. There were people getting onto trains and jumping between cities on trains. There were riders getting towed by motor bikes and motor cars."

Peter Cossins

“On the fifth stage of the race, which went from Bordeaux to Nantes on the western side of France, four of those riders — all supported by La Française — got away from the rest of the pack,” Cossins says. “And they were most of the way to Nantes, and Garin said to his three companions, ‘I hate to tell you this, guys, but I’m gonna win this stage today.’ He was already leading the race. But one of the four guys with him, Fernand Augereau, another Frenchman, just turned to him and said, ‘Well, I think I can win. Why should I let you win?’”

It was a question Augereau would regret asking. Garin ordered one of the other members of La Française to knock Augereau off his bike, which the fellow did.

Undeterred, Augereau remounted and eventually caught up.

“Garin sees him coming up, and he says to his colleague again, ‘Knock him over again!’ Same thing happens, Augereau hits the deck,” Cossins says. “And this time, rather than just ride off and wait for him to get up again, Garin took the rather more decisive step of jumping off his own bike and grabbing hold of Augereau’s bike and jumping up and down on his wheels and smashing them to pieces, rendering the bike completely useless. And then the three of them rode off.

“This was seen by — I mean, there were spectators at the side of the road. And there’s one gentleman standing there, so horrified, he hands his own bike to Augereau, who jumps on it and charges after the other three and caught them again.”

‘Upright And Honest And Strong’

Unhappily for Augereau, his heroic recovery went for naught. Both his tires blew out before he could reach the finish line for the stage. But he had a story to tell when he finally got there, right?

Right. But nobody wanted to hear it.

L’Auto, the newspaper sponsoring the first Tour, failed to mention Garin’s blatant interference.

“They wanted to portray him as this heroic athlete who was doing everything in the right way, to be a kind of stereotype of French manhood -- of being upright and honest and strong,” Cossins says.

The organizers felt that portrayal was a critical part of selling their new race to the French public. And it worked. While the gathering at the start of the race outside Paris hadn’t qualified as a “crowd,” interest had built as the race went on, Garin in the lead. For the final stage, even the previously blasé Parisians had caught Tour fever.

“By this stage, the Tour was such a success that the Parisians turned out in the tens of thousands as well,” Cossins says. “And so they finished in Ville-d’Avray, which is just on the edge of the city. And there was mayhem at the finish. They could barely get the road clear before the riders came through. A car caught fire near the finish line…”

(Perhaps not unusual, in 1903.)

“… Another one broke down on the course and had to be pushed off to the side of the road. The two guys who were racing to win the final stage tangled with a spectator in the crowd and both went down, and that was to Garin’s advantage,” Cossins continues. “I mean, everything seemed to go his way, and he ended up crossing the line first and winning the Tour.”

Maurice Garin defended his title in 1904. He was similarly successful.

“He won it again. And he cheated even more than he did in the first race, and pretty much everyone around him was cheating as well,” Cossins says. “There were riders throwing tacks down, nails and other stuff on the roads, so that the rivals punctured. There were people getting onto trains and jumping between cities on trains. There were riders getting towed by motor bikes and motor cars.”

Wait, what? Riders getting towed by cars? Surely somebody must have noticed that.

“They would trail a thin piece of wire right behind a motor car, which, at one end, had a cork fixed on to the end of it,” Cossins explains. “And the rider would wedge the cork between his teeth. And then get towed along with this thing, this wire, pulling him along.”

The riders probably couldn’t have gotten away with that if the first two Tours hadn’t included night racing.

The particular offenses of Maurice Garin during that race are lost to history, but he was among numerous riders eventually disqualified. The guy who finished fifth got the money.

A Happy Ending For Garin

But the disgrace, if, in fact, there was any, didn’t hurt Garin at all, though he never raced again. Instead he opened a gas station. It was very popular, because motorists soon learned that while he was filling their tanks, Garin was happy to tell them all about his triumphs on the Tour.

“He’d made enough to kind of make a good life,” Cossins says. “And he spent the next 40-odd years after the Tour running his gas station, probably making quite a good living. He was probably quite happy with the way things had gone for him in the end.”

Don’t you love a story with a happy ending? Especially one that has included the hero jumping up and down on another guy’s bicycle and various other outrages against fair play? Comes with the Tour’s territory, at least according to Peter Cossins.

“It’s always been there,” Cossins says. “And just looking back at that race highlights that. Lance Armstrong, I mean, he did bring a good degree of ruin on the Tour de France. He might have been a bully and forced people to do stuff against their will. But, I mean, he was only the same as Garin was 100 years earlier."

The 104th Tour de France is underway this weekend. If you'd like to further explore the sordid beginnings of the world’s most famous bike race, check out Peter Cossins' book, “The First Tour de France."

This segment aired on July 1, 2017.