Advertisement

A Story Of A Divided Maine Town, Somali Refugees And High School Soccer

Resume

"When I was in Lewiston, it felt like its better days were in the rear-view mirror," Amy Bass says.

Bass was in Lewiston, Maine, to attend Bates College. There wasn’t much reason to stay after she graduated in 1992.

"A lot of unemployment. A lot of vacancy," she says. "Things that Maine deals with in terms of younger population moving away."

But Bass became intrigued with Lewiston a little under 20 years ago, when she learned about an influx of families from Somalia.

"So a lot of these folks were coming from other refugee relocation sites, particularly in the outskirts of Atlanta," she says. "They didn’t want big city life. They wanted space for larger families, they wanted security and safety and they wanted good schools."

'Please Tell Friends And Relatives To Stop Coming'

And at first it looked like a good fit. Lewiston certainly had the space: vacant apartments and storefronts. Mainers didn’t have much experience with refugees, but if people wanted to move to Lewiston and help repopulate the place, why should anybody object?

Until they did. Or one of them did, and he was the mayor of Lewiston, Larry Raymond. In October of 2002, he wrote an open letter to the growing Somali community in town.

"It was written on city stationary, although it wasn’t really an official city declaration, saying that the Somali community that has already come is supported and welcomed, and they were done," Bass says. "And to please tell friends and relatives to stop coming."

The letter was fine with some of Lewiston’s residents, the ones who’d heard that the Somalis had been drawn to town by Maine’s welfare system. Rumors had circulated suggesting that the schools had become overcrowded, that the city had been buying cars for the Somalis, that the new arrivals were getting benefits to which long-time residents were not entitled.

Somebody scrawled "Go back to Africa" on a mirror in a school bathroom. But members of the Somali community answered Mayor Raymond’s letter with one of their own. They pointed out that they were working and buying groceries and otherwise contributing to the community.

Changing 'The Way Lewiston Soccer Was Played'

And then there was soccer. Mike McGraw, who’d been teaching biology and coaching the boys’ high school soccer team in Lewiston for decades, saw opportunity in the new arrivals.

"Well, they weren’t from Maine. And I knew that the rest of the world played the game, where the United States kind of just used it as recreation," McGraw says.

Lewiston was a hockey town. After that it was a football town. Basketball matters a lot in Maine. McGraw was a respected coach whose soccer teams had posted winning seasons, but they’d never won it all. Then along came these Somali kids. Some of them had lost family members while being chased from one refugee camp to another, but wherever they’d gone, they’d kicked around balls made of cardboard and cloth.

They had skills, even if they were not entirely game-ready — or, more precisely, ready for Coach McGraw.

"I recall one of the kids saying after a summer game, 'Well, when am I gonna get a uniform?' And I said, 'Well, you have to try out,' " McGraw recalls. "He says, 'Try out? Why try out? I’m good enough. We’re gonna be a champion.' And I said, 'Let’s try out first and see what happens.' "

Soon McGraw faced another challenge. What would he tell the white players who’d expected to be starters — or at least to make the team — and the white parents who’d shared that expectation? McGraw pointed out to them that it was the Somali kids who’d gathered in the parking lot outside the hockey arena after the season’s first snowfall, because they knew it was the first place that would be plowed, the first place where they could kick a ball around.

"It’s pretty easy. If you practice, you play. If you don’t practice, you sit and watch," McGraw says. "Nothing personal. It’s just the way the game is played."

OK, so far. The composition of the players trying out doesn’t change the ethics of the veteran coach, who eventually gets some help from a Somali assistant coach named Abdijabar Hersi.

"My dad, when he first came, he didn’t really like the American style, you could say," says Bilal, Abdijabar's son. "Like, basically, in Europe and other places, they like to play more passing and more, like, skillful soccer. And I’m glad Coach McGraw and my dad talked. And they helped change the way Lewiston soccer was played."

Still, building a team from two disparate groups was a challenge, even though McGraw says the white players understood that the skilled Somalis would help their team get better.

The coach recalls one particular afternoon when the white kids were hanging around together, waiting for practice to start. Down the hill from the field, the Somali kids were kicking a ball around. It must have looked as if two teams were getting ready to play against each other.

"And I told them that for us to be a team, this is how we had to be: we had to practice together, we had to play together this way," McGraw says. "We couldn’t be one group and another group — and that we needed to learn how to trust and work together with each other. And I mentioned that this is also maybe a good way to be in the hallways of the school. And to get to know each other. And maybe interact with each other, go to the movies and things like that. We were pretty good before, but that’s when we started to get a lot better."

"It doesn’t mean they’re going to stay together. Community is still really hard work. But now they know what it feels like."

Amy Bass

Did the Somalis learn to like Maine blueberry preserves? Coach McGraw didn’t say. But he mentioned that lots of folks in Lewiston began trying sambusa, which the coach asked Bilal to define.

"It’s like this tortilla, but it’s, like, filled with whatever you want," Bilal says. "It can be chicken, it can be meats, or anything like that, and a lot of people in our town really, really like that."

Knowing What Community Feels Like

By 2015, about a decade and a half after the Somalis had started making their homes in Lewiston and sharing their cuisine, a lot of people in the town also really, really liked the soccer team McGraw had built into a contender for the state championship.

"There was no doubt in my mind that we were gonna get there," McGraw says. "And then it was just a matter of playing the game the way we were supposed to play."

The Somali families had continued to arrive in Lewiston. As time passed, they had veteran Somali players to help them get used to shin guards, whistles and referees, as well as the rest of the new culture. Still, one of McGraw’s players told him that on July 4th, his mother had hustled him indoors to hide, because she was sure war had broken out.

So, adjustments. But in 2015, Mike McGraw had a team that had excited the city and made it to the game that would decide the state champion.

"4,500 people were at that game — more people than went to the state championship football game that year," Bass says.

And then, despite the fact that Lewiston had built a reputation as a high-scoring team, the final settled into a scoreless battle. McGraw had to be concerned. One mistake or a fluke bounce could lead to the kind of disappointment that he’d often experienced. But the coach says he wasn’t worried.

"I had supreme confidence in our kids," he says. "Even when it got down towards the latter part of the game, when it looked like it was gonna be a tie, it didn’t matter to me. I knew that we were gonna play well enough, somehow, to break through."

A throw-in landed in the middle of the penalty area and bounced toward the far post.

"And one of the players from Scarborough didn’t judge the flight of the ball, and it glanced off his thigh and went in," McGraw says. "It was an own goal. And, you know, it’s like everybody says: We’ll take it."

The community celebrated. And it was a community that high school soccer had helped to build and sustain, which, according to Bass, is what makes the story she found when she returned to Lewiston more than a sports story.

"They had ownership of a really important part of Lewiston history: the city’s first state championship in soccer," she says. "And as one player, one former player, says from the stands that day, 'It was a "we" moment.' And I think that, amidst all of the celebration, the trophy moving throughout town, and a community dinner and national media attention, everything comes together in the 90 minutes of that game.

"It doesn’t mean that they’re going to stay together. Community is still really hard work. But now they know what it feels like. They had that day of knowing what it feels like to be together, to 'bleed blue,' as they say. And they say that once you bleed blue, you always will, in Lewiston."

The Lewiston boys' soccer team won another state championship in 2017. Bilal Hersi played for that team.

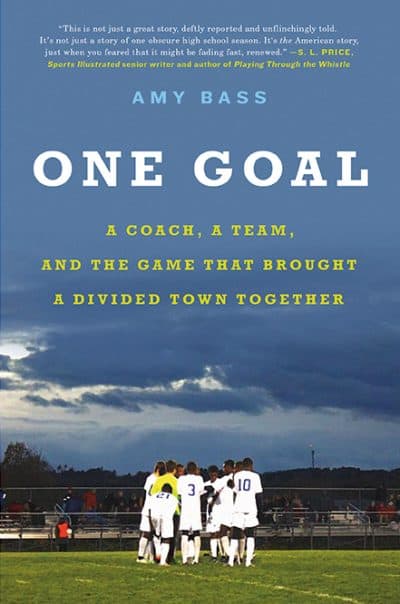

Learn more in Amy Bass' book, "One Goal: A Coach, a Team, and the Game That Brought a Divided Town Together."

This segment aired on April 7, 2018.