Advertisement

Blondy Baruti: Out Of The Congo, Onto The Court, Down The Red Carpet

Lots of kids dream of playing in the NBA. For Blondy Baruti, it was a long-distance dream with obstacles aplenty.

One day, when he was 9 years old, Blondy woke to chaos and his mother’s frantic shouts.

"She was, like, 'We got to go, like, now, now, now.' And I was trying to pack," Blondy says. "She was, like, 'No. We cannot pack. We have to leave now.' "

"Did you have a sense then what you were running from?" I ask.

"I had no idea," Blondy says. "I just saw AK-47s, guns and bombs just blasting everywhere. And people falling down. And we just keep on running, again and again."

In 2000, the Democratic Republic of Congo was filled with families running as hard as Blondy’s. His father had left when Blondy was 3. Blondy, his older sister and their mother had been living in Goma, in the eastern part of the Congo. On the day they fled, as Baruti puts it, "the war finally reached our backyard."

He didn’t know whether that war was part of the on-again, off-again civil conflict in Congo, or a battle that had spilled over from neighboring Rwanda. He had no time to ask. He and his sister and his mother ran into the jungle.

"I just saw AK-47s, guns and bombs just blasting everywhere. And people falling down. And we just keep on running."

Blondy Baruti

"And there was a lot of kids who didn’t make it," he says. "A lot of kids who died on the road because of diseases. And there was famine. No food for days. And also there was a lot of snakes. You never know which one can bite you."

The plan was to walk to Kisangani, just over 400 miles away. On some days, they made progress. On other days, they huddled in the jungle and hoped the armed men they could hear around them wouldn’t find them.

"I used to cry all the time," Blondy says. "There’s no food, there’s no clean water, and you’re sleeping on the ground and in the middle of nowhere. It’s dark. You can’t even set a fire, because if you set a fire, you’re afraid that the rebels might see you guys and kill you guys. And then, after a while, it became normal. It became normal to me."

'You Need To Start Learning How To Play Basketball'

Kisangani might have seemed like a safe destination when the family started running. But by the time they got there, it was just another city to flee. Perseverance, more hungry trekking, begging and a lot of luck eventually brought them to a boat that took them to Kinshasa, nearly 1,600 miles from Kisangani.

There, Blondy found stability — at least compared to what he’d endured to get there. He went to school. There was even time for sports. Which, for a time, meant soccer.

"I was too tall to keep playing soccer. I was very, very tall," he says. "And my friend was, like, 'You need to start learning how to play basketball, because this is not for you. You’re good, but you’re just way too tall for this.' "

Despite days when he had only one meal — and some days when he had none — Blondy would grow to be 6-foot-8.

"And, after a while, I started using it as a motivation. I know, one day, I’m going to go to the U.S., and I’m going to play college basketball, and I’m going to make good things happen,” he says.

Advertisement

Blondy’s devotion to basketball wasn’t quite absolute. He was also the tallest guy in his school’s theater company.

"The main reason why I started to act, it was because there was a girl, Peggy," Blondy says. "She was so beautiful. And I wanted to tell her, 'You are beautiful,' but I was so scared. And she was an actress at my school, so I was, like, 'OK, I want just to learn how to act.' And, thank God, they made me her husband in the play. I even asked our teacher, like, 'Can you make a scene where I can kiss her?' She was, like, 'No, no.' "

The basketball dream was even more unlikely than the dream of kissing Peggy. Dikembe Mutombo made it to Georgetown University and the NBA, but, quick, name another guy from Congo who’s done it.

Still, a big guy who can play draws attention, even in Kinshasa. Blondy was eventually approached by a man who had some connections to private secondary schools in the U.S., a reasonable option, since Blondy was perhaps not ready for college there. He spoke no English.

A New Family

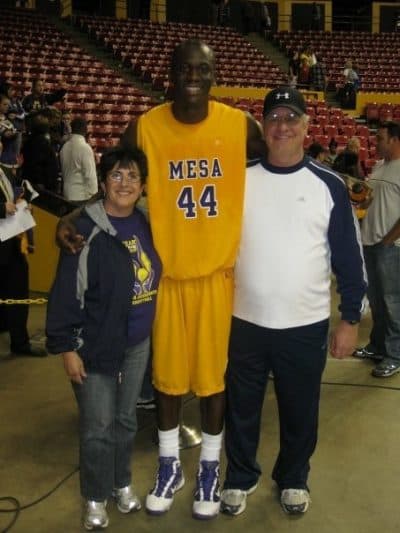

But soon Blondy’s older cousin entered the picture. This was Patrick. He lived in the U.S. He announced that he would manage the prospect’s career. Patrick found a family in Mesa, Arizona, Terry and Laurie Blitz, willing to put up both of them, and then began trying to secure his own future.

"When I first moved in, my cousin just tells me, 'Do not trust these white people,' " Blondy says. " 'Because they don’t love you. Everything they are doing for you, they are writing it down. So one day, when you make it to the NBA, they’re going to make a lot of money off of you.' "

Patrick, who’d misrepresented himself as a successful businessman, was more like a speculator. He’d hoped to profit from Blondy’s basketball success. He’d become the legal guardian, which meant that until Blondy was an adult, he couldn’t officially get free of Patrick.

At an age when lots of U.S. students are starting college, Blondy slowly began getting accustomed to course requirements and basketball in the public school in Mesa.

Pretty quickly, the warning to trust his blood relative rather than Terry and Laurie began to make less sense. According to Blondy, cousin Patrick was sleeping until noon and freeloading off the Blitzes, while Terry and Laurie were treating Blondy like a member of the family.

"She would take me to class before she’d go to work," Blondy says. "They would pick me up. They would buy me food. They would buy me clothes. They would make sure I’d do my homework. Terry would get on me about not practicing hard. And then I started feeling more comfortable being around them than being around my cousin."

A Scholarship And A Shot At A Dream

Terry and Laurie Blitz had made sure Blondy was prepared to take advantage of the basketball scholarship he got from the University of Tulsa. But in just his second season there, Blondy suffered a serious ankle injury.

"It was just so much pain. But I was trying to hold on to that hope that I’m going to make it to the NBA," he says. "And I was, like, 'No, this is all I got. If I can survive war in the Congo, yes, I can survive this injury. I walk about 500 miles through the jungle of the Congo. I play in bare feet in the Congo in 110 degrees outside. Nothing like this happened to me. So why this injury now?' "

That question had no answer. But the question of whether Blondy would ever play pro basketball did have one. It was provided by the doctor who treated Blondy.

"He was, like, 'You just got to let it go, because it’s not going to get any better,' " Blondy recalls. "I collapsed in his office and just started crying. I felt like basketball was my way to help my mom, to help my sister, to help my family back home. But I had to let it go. And I had to move on."

Tulsa Hurricane To Huhtar Of The Yondu Ravager Clan

Where does a 6-foot-8 basketball player move to when he’s told to let basketball go? Blondy had enjoyed the acting he’d done in school, even though he hadn’t gotten to kiss Peggy. Like basketball players, actors got rich. If he succeeded, he could help his family in Congo. Two days after graduation at Tulsa, he was off to L.A.

"I had faith," he says. "I was, like, 'I’m going to go out there. I’m going to become an actor. And I’m going to be in a movie.' "

Blondy’s efforts followed a plotline familiar to lots of aspiring movie stars. His meager funds ran out. He borrowed from everybody he knew. He slept in his car. And then he went back to Terry and Laurie in Mesa. He might be in Arizona to this day, if he hadn’t heard about a TV pilot that needed a tall African basketball player who didn’t have to speak much English.

Terry and Laurie funded his return to L.A., and eventually Blondy got the part. Though the show wasn’t picked up, he eventually parlayed the experience into an opportunity to play a baddie named Huhtar in "Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2." It was a tiny role. His makeup and costume rendered him unrecognizable. But he was at the premiere.

"It was probably one of the best feelings I ever had in my life," he says. "Just to be around all these actors I had always heard of. 'Oh, Stallone. Chris Pratt.' I was like, from the Congo, from the jungle of the Congo, to being at the premiere of 'Guardians of the Galaxy.' I just could not believe it.

Blondy says that during the premier he was "this close" to jumping up and yelling, "That's me, America! That's me!"

"But you're, like, "No, no, no, no...you can't, you can't, you gotta stay quiet," he says.

With assistance, Blondy has written a screenplay about his life and another one about a boxer from Congo whose career trajectory seems oddly familiar. He sees himself as the star.

"Like Sylvester Stallone did with 'Rocky,' " Blondy says. "He wrote something for himself. That’s how he got in."

Yup. That’s how he did it. And he’s nowhere near 6-foot-8. Good luck, champ.

Read more about Blondy Baruti's journey in his book, "The Incredible True Story of Blondy Baruti."

This segment aired on May 12, 2018.