Advertisement

Joseph 'Sport' Sullivan's Little-Known Role In The Black Sox Scandal

Resume

I'm in a small elevator at the Hotel Buckminster in Boston. We're going to the sixth floor. We're going to see "the room." When the doors open, we step into a dark, narrow corridor.

The hotel and its triangular floor plan is more than 120 years old, and it feels like we've entered a maze. We head right, then the hotel's sales manager, Zack Byron, realizes we need to turn around. We almost walk right by "the room." From the outside, there's nothing special about it.

Byron opens the door. The inside is pretty unremarkable, too — except for the view.

From a small space with a couch and a coffee table, we can see Fenway Park in all its glory. Well, mostly, the back side of the Green Monster. But it's still Fenway, and somehow the view feels special, strangely intimate, like we've been given a backstage pass.

A Baseball Expert And Math Whiz

On Sept. 18, 1919, gambler Joseph "Sport" Sullivan and White Sox first baseman Chick Gandil looked out at the same view from the same hotel windows.

"This is where the scandal was hatched, and we're standing right where a table would've been, where the scandal participants would have sat," Byron says.

It was here, in Room 615, where according to Eliot Asinof's book "Eight Men Out," Gandil told Sullivan, "I think we can put it in the bag!"

The basic idea: Pay a group of White Sox players to throw the 1919 World Series.

But who was Sport Sullivan, the man who helped hatch the biggest scandal in baseball history? How did he get in the middle of it, then essentially get away with it?

Back then, there was a good chance you would find Sullivan's distinctive figure in the gamblers' section at Fenway Park.

Yes, Fenway had a gamblers' section in the right field pavilion. Betting took place in full view of everyone, including policemen who did little, if anything, to stop it.

Sport Sullivan was 6-feet tall, whip-smart, confident, charismatic and unquestionably stylish.

"He was called 'Sport,' by the way, not because he bet on sports games, but because he dressed as a sport," says history professor and book author Bruce Allardice, a White Sox fan from Chicago who's written more about Sullivan's life than anyone else. "He was a very neat, expensive dresser, you know, thousand-dollar-Brooks-Brothers-suits type of guy.

"He was nationally known not just to the players, but to the gambling fraternity as the go-to man in Boston. He was, among other things, an early Sabermetrician before people really paid attention to baseball statistics. He was a baseball expert, a legitimate baseball expert."

Sullivan was also a math whiz with a remarkable memory. He could keep track of 30 bets at a time without writing them down. He could calculate payouts in his head.

He also paid players for inside information about injuries and starting pitchers.

And Boston ace Cy Young said Sullivan tried to bribe him and his catcher to throw at least one game of the 1903 World Series. The pitcher told a sports reporter that, when he heard the offer, he punched Sullivan in the jaw.

That wasn't the only time Sullivan suffered some unpleasant consequences.

"He was arrested several times for gambling, but always paid the fine and was back in the ballpark the next day," Allardice says.

And back to the gamblers' section at Fenway, or the one at Boston's other Major League ballpark, Braves Field.

The 'Hub Of Baseball Betting'

"In the early 20th century, Boston was considered the hub of baseball betting activity," says Jacob Pomrenke, who chairs the Black Sox Scandal Research Committee for SABR, the Society for American Baseball Research. "Harry Frazee — the notorious Red Sox owner who later sold Babe Ruth to the Yankees — had a lot of opportunities to help clean up the game before the 1919 World Series. But he always chose to look the other way because as long as the gamblers were buying a ticket, he didn't care too much what they were doing in the stands."

This was the baseball climate where Sullivan thrived and made friends with players. The better the friend, the better the inside information.

"That's part of Sport Sullivan's modus operandi," Allardice says. "He'd invite visiting teams, and, of course, the Red Sox also, to shoot pool with him at the bar. Have a drink, you know, at some local restaurant or something like that, or spend a day relaxing at his country house."

Once, Sullivan brought a group of White Sox players to his house for an all-night card game.

"The players knew they were sort of being set up to be used. But that was the style of baseball," Allardice says. "He was not the only gambler doing these things at that time."

White Sox first baseman Gandil first met Sullivan in 1912 — seven years before that meeting at the Hotel Buckminster. It was a long, profitable friendship built on Gandil feeding Sullivan inside information.

But fixing the World Series was something else entirely. They figured it would take some serious cash to get a group of White Sox players on board — $80,000, or the equivalent of $1.2 million in today's money.

Sullivan knew he couldn't finance it alone.

Enter Arnold Rothstein.

A Trip To Chicago

The notorious New York City mobster often gets credit for pulling off the fix. That's probably because a thinly veiled fictional version of Rothstein, a character named, "Meyer Wolfsheim," appears in "The Great Gatsby."

But really, Rothstein didn't come up with the idea. He just bankrolled it.

"Rothstein knew that if Sullivan comes to you with a deal, he knows what he's talking about and he's capable of pulling it off," Allardice says.

Sullivan headed to Chicago with $80,000 for the eight players now in on the fix, plus more money for placing bets.

While he was there, "He went to the chamber of commerce and got a list of who in the chamber of commerce was likely to bet on baseball games and made private bets with them, rather than going publicly to a hotel and everything like that," Allardice says.

But Sullivan and Rothstein weren't the only gamblers in on the fix.

"Rothstein knew that if Sullivan comes to you with a deal, he knows what he's talking about and he's capable of pulling it off."

Bruce Allardice

The players wanted more money for throwing games. And between the time Sullivan and Gandil first conspired at the Hotel Buckminster and the time Sullivan arrived in Chicago, the players had brokered other deals with other gamblers.

The problem: The more people in on the fix, the more likely word would get out.

A Missing Link

The White Sox entered the Fall Classic heavy favorites against the Cincinnati Reds, but they lost the nine-game series, five games to three. Rumors swirled about a fix.

By September 1920, almost a year after that meeting in Room 615, players and gamblers were talking to reporters and testifying before a Cook County Grand Jury in Chicago.

Talking to the Lowell Sun newspaper, Sullivan vowed to testify. He didn't want to become the scapegoat in the scandal. He told the paper: "I have the whole history of the deal from beginning to end. I will tell the grand jury or any other officials the whole inside story of the frameup."

But Sullivan never went before the Grand Jury. The prevailing theory is that Rothstein exerted his influence to keep Sullivan off the stand. Even after Rothstein died, Sullivan never told his side of the Black Sox Scandal.

Sullivan was banned from ballparks. His math skills, remarkable memory and pricey suits faded. Sullivan died at 78, almost 30 years after he helped hatch the biggest scandal in baseball history.

"One of the reasons that we consider Sport Sullivan to be one of the biggest missing links about the Black Sox scandal is that he took a lot of his secrets to the grave with him when he died in 1949," Pomrenke says.

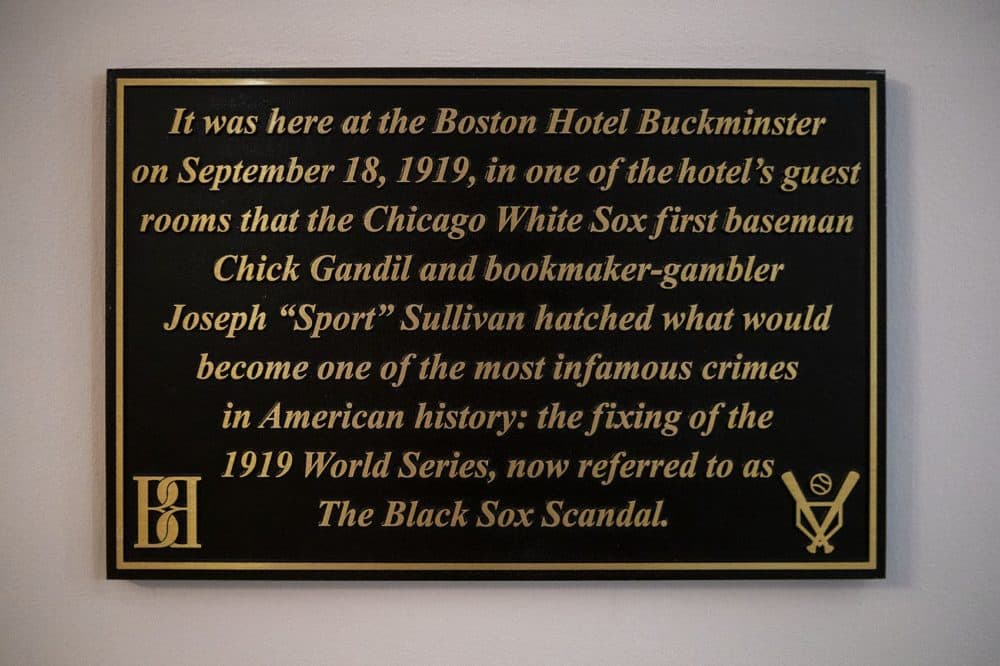

Still, Sullivan gets remembered at the Hotel Buckminster in his hometown of Boston. There's a plaque in the lobby that commemorates the meeting between Sullivan and Gandil in Room 615.

That's where I am when I ask hotel sales manager Byron if guests ever request to stay where the Black Sox Scandal was hatched.

"Occasionally we get some real baseball aficionados who are really familiar with the whole story. But that's maybe three or four times a year," Byron says. "The vast majority of people who stay here have no idea.

"There's a story here at the Buckminster," Byron adds. "It's kind of like a local legend that up on the sixth floor you can occasionally — if you're walking by yourself late at night — you can occasionally feel somebody kind of walking behind you.

"And some of our guests, totally independent of each other, have told us that they'll do a quick turnaround and look, and they see a man in a sport coat with a vest and a fedora walking around. Some people have claimed that they've seen him in this room itself. Some people say it's Sport walking around. Who knows?"

Maybe after 100 years, Joseph "Sport" Sullivan wants to be more than a missing link. Or, maybe, he just likes the view from Room 615.

This article was originally published on October 18, 2019.

This segment aired on October 19, 2019.