Advertisement

Commentary

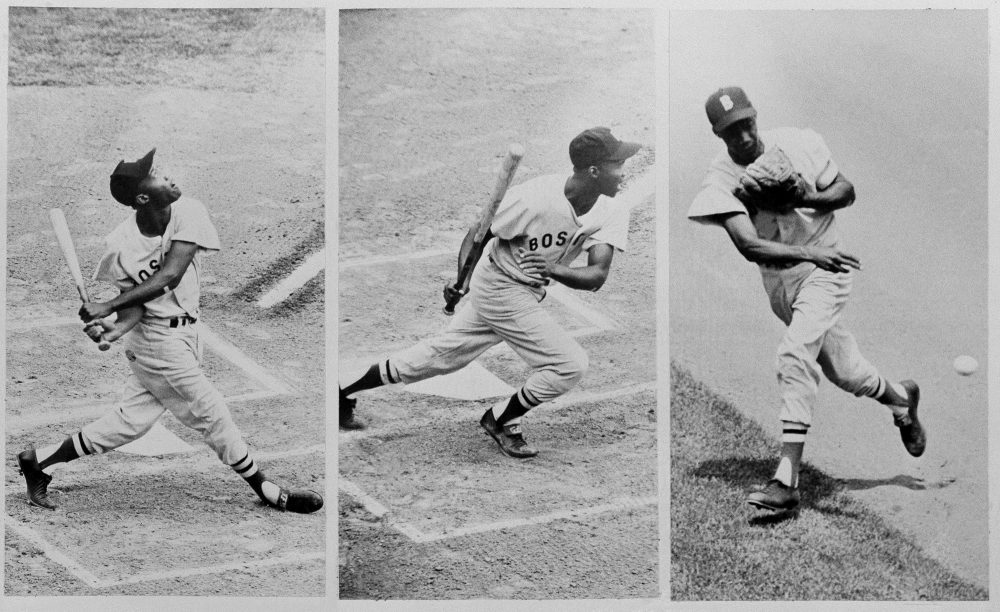

Let’s Rename Yawkey Way For The Man Who Ended Segregated Baseball: Pumpsie Green

The Red Sox are right to want to rename Yawkey Way, the section of road astride the ballpark that celebrates the man who owned the team for more than four decades. However loyal we fans may be to our hometown team, we should acknowledge our shameful history as the last city in the majors to bring African-American players onto the roster.

Thomas Yawkey shrugged off growing pressure to hire a black player until 1959, when he finally brought up infielder Pumpsie Green, a dozen long years after the Brooklyn Dodgers recruited Jackie Robinson.

The Red Sox’ principal owner, John Henry, says he is haunted by that legacy, and wants to rename Yawkey Way. Thus the Sox — and by extension, Boston itself — have joined the national discussion about symbols of slavery, rebellion and racism.

For many of us in Boston, this isn’t ancient Civil War history or distant civil rights unrest. This is about our own city’s racial divisions, within our lifetime, from our neighborhoods to schools to beloved Fenway Park. And we shouldn’t forget the more recent taunts from fans aimed at black players on the field, including C.C. Sabathia and Adam Jones.

After a weekend when tens of thousands poured into Boston’s streets to reject hatred and white privilege, Henry’s anguish is timely and appropriate.

So let’s rename Yawkey Way for Elijah “Pumpsie” Green. After all, when Green took the field for the Sox on July 21, 1959, as a pinch-runner, he not only broke the last disgraceful color line in the majors; he effectively ended segregated baseball.

My preference is for Green Way, which would echo the name it replaces, and recall the New Boston of the Greenway and its Leonard Zakim Bridge. A friend prefers Pumpsie Place. Maybe Pumpsie Green Way.

Naming the street for Green would provide a constant reminder of the city’s history — and its modern challenges. Kids going to their first game would ask, “Dad/Mom, who was Pumpsie Green?” That’s more meaningful than naming the street for the already celebrated David Ortiz or another sports hero.

It’s unimportant that Green had a low-impact and relatively short career (lifetime average .246 over five seasons, four with the Red Sox and one with the Mets, from 1959 to 1963). He has lived a decent life by all accounts, serving his community as a high school baseball coach and teacher in Berkeley, California, for more than 20 years after his baseball career.

Advertisement

Pumpsie Green is 83 now. He has been back to Fenway, throwing out a first pitch in 2009, but he hasn’t been a major figure in the reminiscences of recent years and never sought the limelight.

In a NESN interview that year, he recalled some of the racism he experienced even after joining the ball club. He said he and other African-American players often had to stay with black friends in cities where his white teammates stayed in segregated hotels. He had to find taxis willing to take him into those black neighborhoods after games. Once, during spring training in Arizona, when Green was refused service in a restaurant, the entire team got up and left without eating.

At a ceremony in Green’s hometown of El Cerrito, California, in 2012, Mayor Bill Jones presented a proclamation and a warm salute: "Pumpsie Green became history. He was not only the first African American to play for the Boston Red Sox. He ended segregation in major league baseball."

I first went to Fenway with my dad for a game in 1960, when I was 7 years old. I remember Ted Williams playing that day, in his last season. I like to think I saw Pumpsie Green, too, making his quiet history.

If we’re renaming roads in our city, let's keep the focus on what was wrong in Boston and what one man did to change it. That’d be a monument reminding us of the values the modern Red Sox seek to elevate.