Advertisement

Review

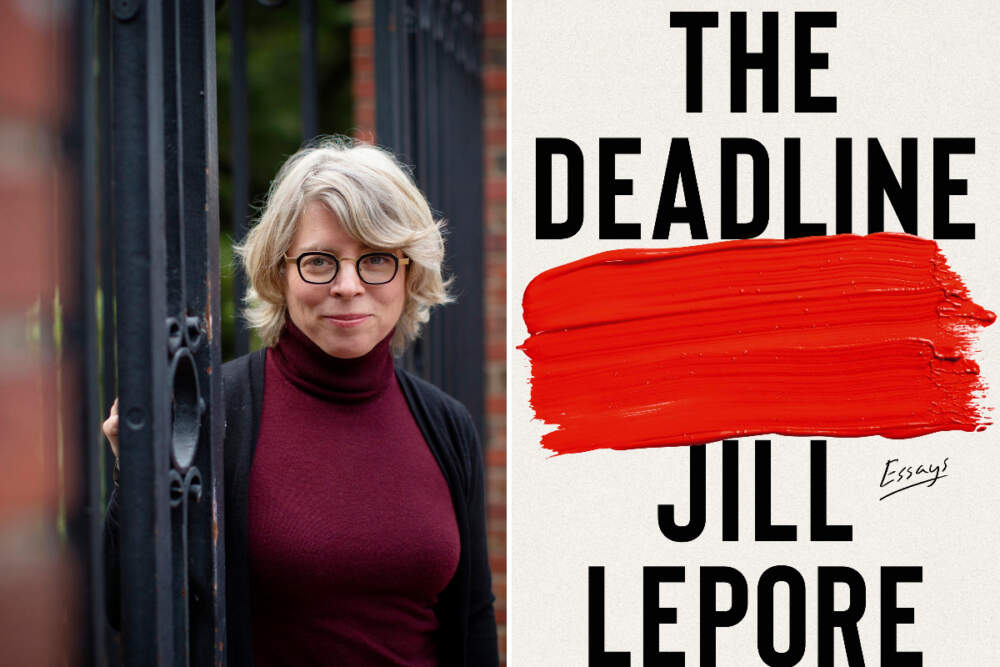

Jill Lepore's new essay collection is a bracing exploration of modern history and culture

If newspapers are the first rough draft of history, magazines can offer a multi-dimensional second draft. A magazine essay, its author afforded the luxury of more writing time, can deliver in-depth research as well as a fresh perspective on a current event or trend. This is what historian Jill Lepore’s “The Deadline: Essays” brilliantly offers.

“The Deadline” is a collection of 46 essays, most of which were first published in The New Yorker, where Lepore is a staff writer. As a whole, they constitute a bracing and deeply considered guide to the ground-shifting cultural and political events of the past 10 years.

Lepore grew up in West Boylston, just north of Worcester. She has won numerous awards for such essays and books as “These Truths: A History of the United States,” “The Secret History of Wonder Woman” and “The Name of the War: King Philip’s War and the Origin of American Identity.” Lepore is also the David Kemper ’41 Professor of American History at Harvard.

“The Deadline” is divided into ten sections (with titles like “The Disruption Machine,” “Battleground America” and “Valley of the Dolls”), and each essay also stands on its own, making this book an attractive all-you-can-read buffet.

Subjects range across a considerable landscape. There are revelatory profiles of historic figures such as Herman Melville and Rachel Carson and essays on cultural battles that have roiled the nation (including public school curriculums, reproductive rights and gay rights). There are also essays that simply enrich your understanding of American culture, like “Burned,” which explains how “burnout” morphed from an early 1970s label only applied to drug users to a 1980s term for overwork.

Lepore has a nearly musical gift for structuring a narrative with rhythms that keep you engaged, harmonizing compelling anecdotes with background facts and statistics. This can be more difficult than it seems, telling a well-researched tale well. Lepore is a master at it, illuminating a topic with pertinent, often surprising facts without flooding the main theme with unrelated information. History is, after all, a story.

Reading essays on politics in 2023 carries a particular urgency. The 2015 essay “Politics and the New Machine” traces how political polling, once a mere accessory, mutated into a paramount news force and how, according to Lepore, it has made American political life “frantic, volatile, shortsighted, sales-driven, and anti-democratic.” “After the Fact,” an article originally published in 2016, tracks how, due in part to the internet, a hold on a shared reality gradually loosened. Lepore notes the then-new phenomenon of certain politicians no longer believing “in evidence, or even in objective reality.” A few years and a political lifetime ago, and here we are on the verge of the 2024 campaign in an exceptionally rocky political landscape, which Lepore had warned about during Trump's first run for president.

Some essays connect cultural dots in new ways. With “It’s Still Alive” (one of three essays that made Lepore a 2019 Pulitzer Prize finalist in criticism), Lepore interprets Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” in part as an allegory of slavery, noting how Mary Shelley was well aware of slavery in Haiti and refused to eat sugar because it was harvested by enslaved people. Lepore highlights how Dr. Frankenstein “made use of other men’s bodies, like a lord over the peasantry.” The creature understands the true horror of his origins only after he learns to read, which Lepore compares with Frederick Douglass remarking on how, having learned to read, he was given “a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy.”

“The Parent Trap,” covering education battles over what should be taught in public schools and what books can reside in a school library, illustrates Lepore’s skill at setting a seemingly new issue into a solid historical context. Reaching back to the 1925 Scopes Trial, which argued whether or not evolution should be taught in Tennessee public schools, Lepore highlights how a clash over a specific topic is often about much more. Then, as now, it was about “the rights of parents against the power of the state,” not to mention parents against “the whole Progressive package.” Lepore notes that current groups like Moms for Liberty are “annoyed at the vein of high-handedness ... laced with … contempt for the rural poor and the devoutly religious.” That said, she still concludes public schools must teach all history. Choosing the teaching of actual events over any discomfort that may bring, Lepore rightly notes that “history as doctrine is always dangerous.”

Lepore’s 2019 essay “Hard News” is about the demise of local newspapers and print media in general. It’s one of Lepore’s best, showcasing her storytelling and descriptive prowess. It begins with Lepore and her siblings helping their father deliver the Worcester Sunday Telegram: “The wood-paneled tailgate of the 1972 Oldsmobile station wagon dangled open like a broken jaw, making a wobbly bench on which four kids could sit, eight legs swinging.” After neatly setting time and place, Lepore widens the lens to construct an annotated timeline of conglomeration, digitization and ultimate surrender to algorithms. She speaks succinctly and honestly about the damage done by the shift from a variety of local and national newspapers to narrowly curated mediums like Facebook’s News Feed.

Read in aggregate, “The Deadline” makes an indirect but strong case for a liberal arts education. Lepore’s agile, endlessly inquiring mind creates original frameworks in which to consider complex issues. Her writing conveys a habit of curiosity, one worth cultivating, especially in this era of half-truths donning the clothes of the righteous.

The book’s first two essays are personal ones, in which Lepore introduces herself and shares histories of her family growing up, her own family and kids and a very dear friend who died too young. In the Introduction, Lepore notes, “I never set out to study history. I only ever set out to write.” How gratifying for the rest of us that Lepore combined the two — exceptionally well.