Advertisement

Commentary

Nostalgia is lovely, and a waste of time

A few weeks ago my husband and I got together with my old boyfriend Craig and his current, 60-something girlfriend.

For two achingly long years — when I was 17 and 18 years old — I was smitten with Craig. We were counselors together at what was, even then, a ramshackle old camp in Michigan, a co-op founded in 1938 with a mission to “… show the “superior advantages of cooperation as a way of life.”

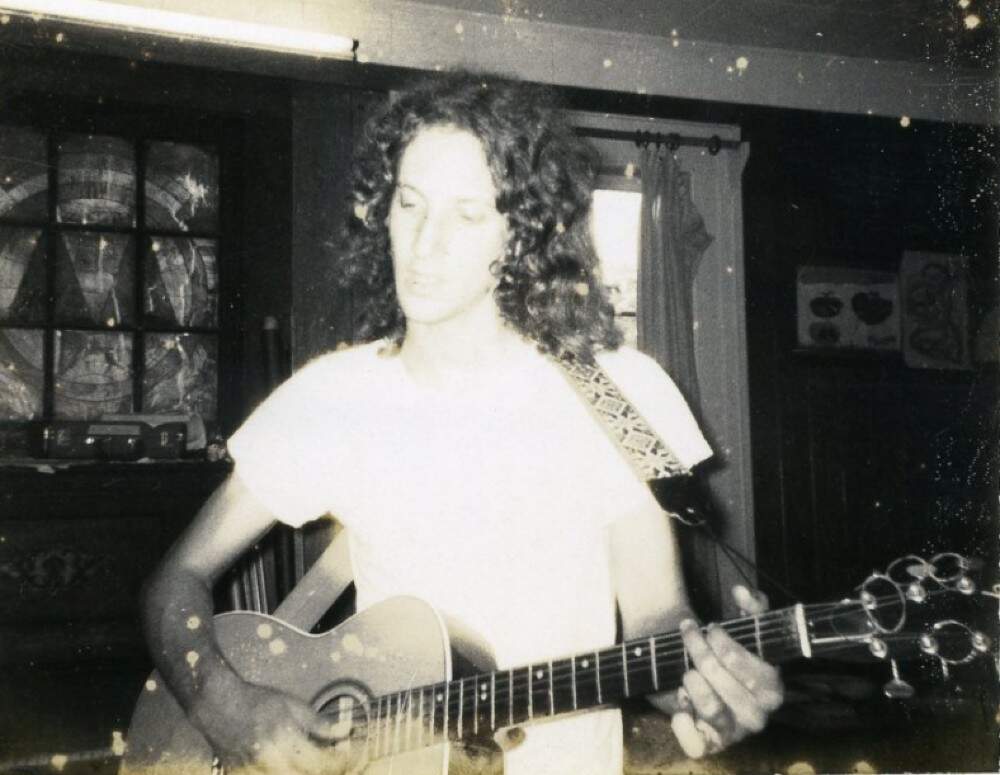

During my time there, 1971 to 1972, peace, love and the values of cooperative communalism were in the air. So too was the music of Bob Dylan, which Craig played on his guitar every night. After our campers had finally gone to bed, he would sit on a cot in his tent in the middle of the pine forest, his deft fingers and long hair radiant in the lantern’s golden glow, and sing “Bob Dylan’s Dream.” The lyrics — an ode to youthful friendships — were far from Dylan’s best, but the tune was plaintive and haunts me still.

By the old wooden stove where our hats was hung

Our words was told, our songs was sung

Where we longed for nothing and were satisfied

Joking and talking about the world outside

With hungry hearts through the heat and cold

We never much thought we could get very old

We thought we could sit forever in fun

And our chances really was a million to one

The languid days of summer, the pines, the long light, the wondrous warmth of first love that seems to flush every pore — this was the perfect recipe for nostalgia.

But nostalgia isn’t always retrospective. Even then, as I was living those moments, I believed that the gestalt of that time, that person, that place, that song would be something I’d long for decades into the future. It was an almost out-of-body experience in which Future Me exhorted cross-legged, poncho-clad Present Me: Remember this.

As is evident, I did. But what I felt was an anticipatory nostalgia, a paradoxical force that led my appreciation for the present moment to pull me out of it. And underlying it was the assumption that as I got older, I’d long for these good old days.

But I don’t. As I age, I find myself looking back less and less often. It turns out that nostalgia is a luxury that I neither want nor can afford, not when time is short and the world is on fire. Even as my joints get creakier, the climate gets hotter, and the prospects for peace within and between nations grow increasingly dim, it rarely occurs to me to seek solace in gauzy scenes from the past.

That’s because the crisis-driven present demands that we lean in and urgency is intrinsically forward-looking. I’m much more consumed by my need to use my time well than to relegate it to reminiscing, to celebrate who and what I have as much as I mourn who and what I’m losing.

I’d like to say that I succeed in this, that I start each day with joy and a clear sense of mission, but that would be a lie. On many days this summer when the valley I live in was clouded by wildfire smoke, and on most days since Hamas’s grotesque attack on Israelis and Israel’s brutal response, I’ve felt more dazed than focused, more paralyzed than purposeful.

But I haven’t felt wistful for days gone by. Crisis trumps yearning as a catalyst to action. The past has passed, and we must build a future out of imagination and tenacity, even if — like tides and lava streams — hope ebbs and flows.

When Craig and his girlfriend came to stay with us, it was only the second time in over 55 years that we’d seen each other. We effortlessly picked up where we’d left off, though, talking about music, politics, our (now deceased) parents, our siblings, our hopes and fears and creative pursuits. Craig told me about the musical he’d just written about John Brown; I told him about the historical novel I’m writing about a utopian community. And though it was faded and limp, a shared idealism remained the thread running through our conversation.

I did succumb to one bit of reminiscing.

“I have such vivid memories of sitting in your tent listening to you play “Bob Dylan’s Dream,’” I told him.

“Really?” he answered after a pause. “I don’t remember playing it. In fact, I don’t remember the tune at all. How does it go?”

For a moment I thought about singing it. But I didn’t. I have a different voice now, one better suited to new songs.