Advertisement

What's the quickest way to cool off a block of triple-deckers? Research says: paint the roofs white

A new report from Boston University suggests that painting the flat black roofs of Boston's brownstones and triple-deckers white could be a quick, cost-effective way to significantly reduce summer temperatures in some of the city's hottest and most vulnerable neighborhoods.

The report builds on recent research by co-author Ian Smith, a PhD candidate at Boston University, which compared the cooling effect of tree cover, grass, and white roofs across seven U.S. cities. His research found that both tree canopy and white roofs were important tools for Boston, but white roofs might offer more bang for the buck in neighborhoods with little room to plant trees.

And even in neighborhoods with space for new trees, adding white roofs as well could offer quicker relief from heat.

'It takes time to reap the benefits that you get from additional tree canopy," said Smith. "If you were to plant a row of new saplings on a city block, it could take decades in order to achieve real cooling impacts from the shade ... whereas if at the same time in the spring you converted the roofs of the buildings on that block to cool roofs, you would reap the benefits of that conversion that summer."

Widespread white roofs — or other "cool roofs" made of reflective material — could also cut back on greenhouse gas emissions and energy costs by reducing the need for air conditioning in the summer.

"For once, the unique architecture of Boston makes this solution a little bit easier than in some other cities," said report co-author Lucy Hutyra, a professor in the Department of Earth & Environment at Boston University. "Most other cities don't have this kind of dominance of flat black rubber roofs like Boston does."

Heat kills more people in the United States each year than any other natural disaster. And urban heat islands — steamy city blocks where dark pavement, black roofs and few trees make temperatures consistently higher than surrounding areas — are especially dangerous, with risks increasing with climate change. The hottest city blocks can see summer temperatures up to 10-12 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than other parts of the city.

There are various ways to lower local temperatures, like planting trees, removing dark pavement, and installing white roofs that reflect sunlight. While Boston’s heat resilience plan points to a need for cool roofs, the focus is on commercial or city-owned properties.

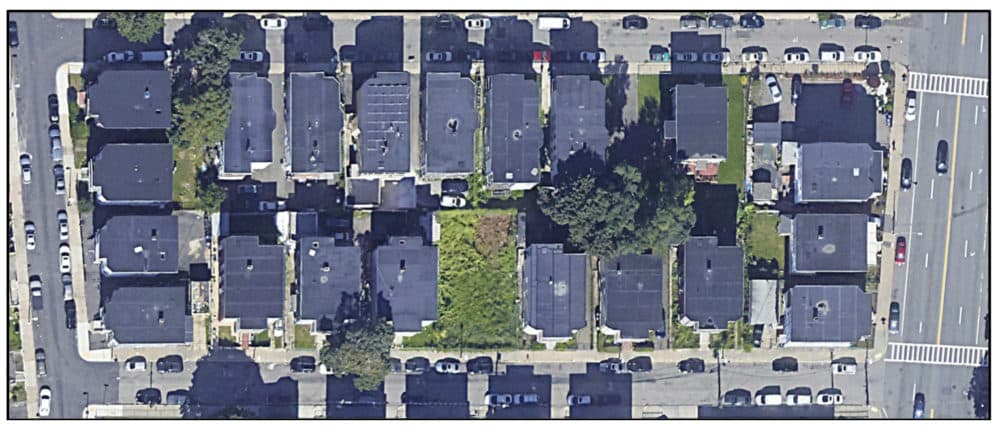

Rooftops account for 20% of the total land area of Boston, and within poor communities of color, more than half of the roofs are flat and dark.

"If you look at the Earth from space on Google Earth, you see that a lot of these dense residential city blocks are 60, 70, 80% flat, black rooftop, and you can hardly even see the ground," said Smith.

The report says that increasing the solar reflectivity of a Boston city block's roofs by 10% will reduce average daytime summer temperatures by more than 3 degrees Fahrenheit within the block.

Cool roofs do have some issues. While they start lowering temperatures immediately, their effectiveness decreases over time as soot and dirt mar their surface. And a white roof could make a house colder in the winter, too — assuming the roof isn't covered with snow, anyway — leading to increased heating bills.

And, of course, someone has to pay to install them.

The report suggests that the Cool Roof Incentive Program in Louisville, Kentucky, which offers subsidies of $1 per square foot to retrofit roofs, could be a model for Boston. As of September 2022, the program had led to the the installation of over 1 million square feet of cool roofs across 260 buildings.

"I love trees and we need to plant trees. And Boston does not have enough canopy," Hutyra said. But, she said, cool roofs offer a targeted, low-cost-solution. "This particular solution is geographically concentrated in the areas with highest need, because those buildings with this flat black rubber roof are in the same places where you have the highest temperatures and the most socially vulnerable populations."