Advertisement

After Independence, Making New Art For A New India

On midnight Aug. 15, 1947, after being under British control since the 18th century, India won its independence. In New Delhi, the government assembly cheered after the clock struck 12.

“India will awake to life and freedom,” Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru proclaimed. He called for “ending of poverty, ignorance, disease and inequality of opportunity."

It was a heady moment of promise, but already the division of the subcontinent into mainly Hindu India and Moslem-majority Pakistan had sparked fighting and mass migrations that would leave some 500,000 to 1 million dead. Including Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of nonviolent protests against British rule in the 1920s that grew into the independence movement. He was assassinated by a Hindu nationalist on Jan. 30, 1948.

“Midnight to the Boom: Painting in India after Independence” at the Peabody Essex Museum (161 Essex St., Salem, Feb. 2 to April 21) assembles nearly 70 works by 23 artists to survey the nation’s creativity from 1947 to the country’s economic boom in the 1990s. Drawing on the 1,200-works in the museum's Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection of modern Indian art, which the museum calls the “foremost public collection of Modernist Indian art outside that country,” the exhibit aims to show how Indian artists, finally free of British colonial rule, began to redefine what it meant to be Indian.

The Herwitz collection was acquired by its namesake Worcester couple over three decades and donated to the museum in 2001. (Their wealth came from their handbag company Davey’s.) Traveling in India in the 1960s, curator Susan Bean says, “They began to discover this art scene that was not visible from here. … It had very little exposure in this country.”

M.F. Husain’s 1951 painting “Man” opens the exhibit. A black man, with his hand on his chin like Rodin’s “Thinker,” sits amidst an array of Cubist figures—what might be a goddess and incomplete female sculptures, an upside-down man, a bull. Bean calls it, “A kind of tale of what it means to be a creative artists in the new India, with this swirl of East and West, ancient and modern, good and evil.”

Except that the painting’s intent isn’t nearly that clear—or persuasive. Husain and other leading Indian artists of the independence generation, whom the exhibit dubs “Pathbreakers,” strove to make transcendent, epic, humanist works that spoke to their historic moment. They wanted to make art that was uniquely Indian, in particular including figures so they could address contemporary Indian life, while also cosmopolitan in its incorporation of the language of Western Modernism. But the hybrid often fizzles because Western Modernism—particularly the abstracting impulse that Indians took up—was not built to talk about the world, but to talk about art, about color and shape and composition.

Advertisement

Another artist of this generation, Tyeb Mehta paints hollow-eyed figures on flat planes of bright colors divided by jagged diagonals symbolizing the traumatic partition of India and Pakistan. But like Husain, his formal simplifications—such as abstracting the figures until they become schematic—obscures and muffles the emotional power of his subject.

The middle of the show focuses on artists whom Bean dubs “Midnight’s Children”—artists born in the decade before independence, who came of age in the new democratic socialist republic and felt the idealism of independence blunted by persistent poverty, inequality and economic stagnation. Instead of epic, cosmic, cosmopolitan notions, these artists turn inward. As Bean frames it, their art is about ordinary, everyday India. It’s subjective and folksy.

Here the standard bearers are Bhupen Khakhar, whose 1980s narrative, faux “naïve” paintings of people riding in a taxi or a man pregnant with twins recall the dreamlike paintings Italian artist Francesco Clemente was making in the 1980s; Bikash Bhattacharjee, whose moody realist paintings of the denizens of his native Calcutta were inspired in part by Andrew Wyeth; and Manjit Bawa, who is represented by a painting of a purple person seeming to scale a giant claymation sea anemone.

In the exhibit’s final section, Bean dubs Indian artists of the 1980s and ‘90s the “New Mediators.” They responded to the economic boom after the liberalization of Indian economy as well as renewed Hindu-Muslim conflict. “There’s a new political edge to what they create,” Bean says.

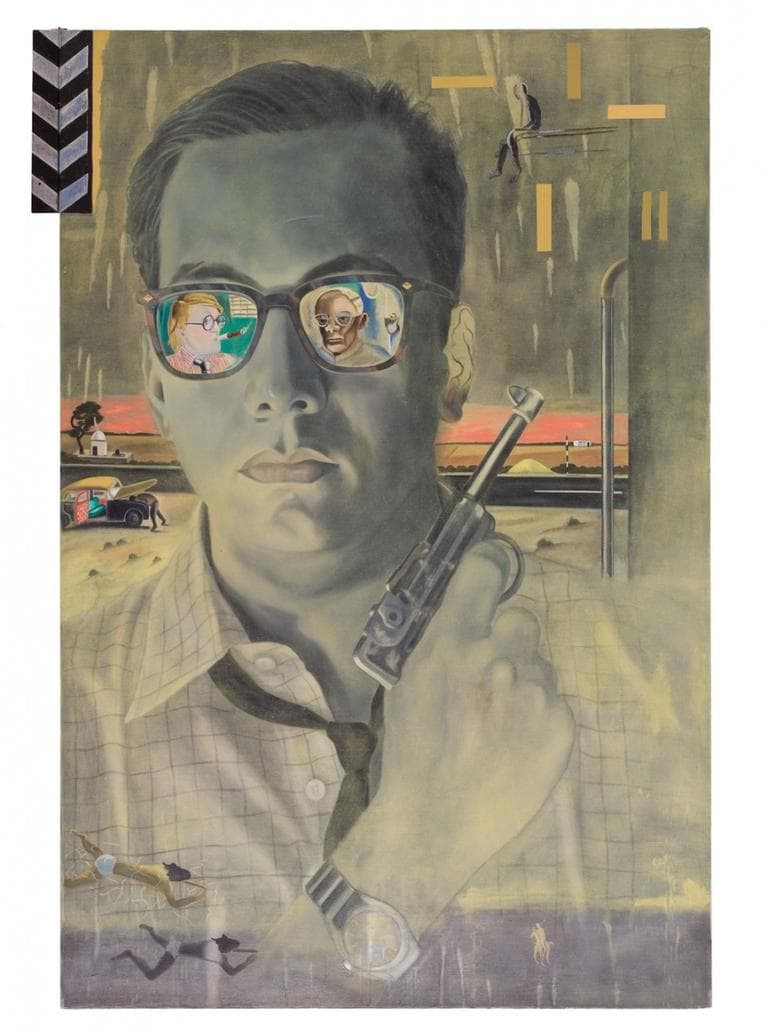

Atul Dodiya paints himself as a movie bad boy brandishing a gun in his 1994 canvas “The Bombay Buccaneer.” Images float about him—a swimmer, a horse rider, a man fixing a car. It deploys the postmodern image sampling of 1980s American art star David Salle. While Salle’s images often seem chosen randomly or for shock, Dodiya seems to want to imbue his references with meaning, such as in “The Flood in Dhaka” (2002), in which he painted a man’s head and fish directly on a shop shutter. If the metal shutter is rolled up, you find inside a painting of a boy, man and two goats floating on a raft and the disembodied head of what appears to be a deity. The movie painting has a kind of cool allure, but the postmodern aloofness and preciousness in his work often blunts the paintings’ emotional resonance.

In the 1990s, painting became less central to Indian art as the rising economy and the growth of the international art fairs and biennials prompted Indian artists to take up installation art, video and other means prized on the international circuit.

Compare Ranbir Singh Kaleka’s 1983 painting “Family—I” to his 2010 video triptych “Sweet Unease.” The first is a cryptic, dreamlike painting of a boy surrounded by two women and a man amidst a floating fence, arch and foliage. He renders it in radiant reds, greens, browns and blues for a hallucinatory effect. But the video installation depicts two men eating in “paintings” set up on easels. Periodically they stand up, wander off onto the wall between the canvases, and wrestle. As Indian artists adopted new media, their styles grew more familiar and fit more neatly into the Western art historical narrative. But in the work of artists like Kaleka, the magical subjectivity of the paintings often turns mundane and impersonal in video.

Ultimately, “Midnight to the Boom” is an effort to revise and enlarge the West’s version of post-World War II art history by incorporating another global story—post-independence Indian art. For the past generation in America, at the end of Western high Modernism, art institutions have been reconsidering what got overlooked. First they looked to women and people of color in the U.S., then to artists in Japan and China, to art from Africa and the rest of the Americas.

U.S. institutions are just beginning to get around to modern India. As represented in the Peabody Essex’s collection, it doesn’t snap neatly into the mainline Western Modernist narrative of the artists of Paris and New York pushing toward ever greater abstraction, toward Minimalism, toward Conceptualism. Instead Indian art’s adherence to the figure, to psychologically-charged color, to symbolism, and to social engagement is more like art that emerged outside the Paris and New York mainstream—the post-World War I German Expressionism of artists like Max Beckmann, Romare Bearden’s collages of African American New York, London painter Francis Bacon’s tortured people, the flinty Yankee realism of Andrew Wyeth, New York painter Alice Neel’s diaristic scenes, the gonzo cartoons of Peter Saul in California and Jim Nutt and Roger Brown in Chicago.

Often artists working outside the mainline are most interesting when they define themselves in difference or opposition to the center. Could the Indian artists here have been held back by their worldliness, by being too open to Western styles? Their hybrid of European and American and South Asian often seems to dilute the force of each one.

So “Midnight to the Boom” is more compelling as social history than as art. But a sample of 23 artists from four decades isn’t enough to make definitive judgments.

“There are these stories about art. They’re the established narratives,” Bean says. “There was a real problem of no place to put this art [in standard histories]. When the Western art world finally got around to acknowledging Asia had art—this goes for China and Japan too—they wanted Asian art to be different. It was a foil for Western art.”

“What do you do when art hybridizes like this?” Bean asks. “You can’t put it in a cubby hole.”

This program aired on February 5, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.