Advertisement

Realism Was So Uncool—Until Richard Estes And The Photorealists Came Along

Realism was practically the most uncool thing an artist could do at that point. It had been that way for a couple decades when Richard Estes moved to New York from his native Illinois in 1958. But he arrived as the American fine art avant-garde was at a turning point.

Everyone was in thrall to Jackson Pollock’s splashy drip paintings, Willem de Kooning’s creamy calligraphy, Mark Rothko’s hovering clouds of color, and other Abstract Expressionist paintings that came out of New York in the late 1940s and made the city the capital of the Western art world. But Estes, like many American artists in the 1950s and ‘60s, was looking to do something different.

He experimented with a hybrid in a brushy painting from 1964 of people seated on benches in New York’s Central Park. Part realist, part abstract, it came off as half-baked and Estes soon moved on from the style.

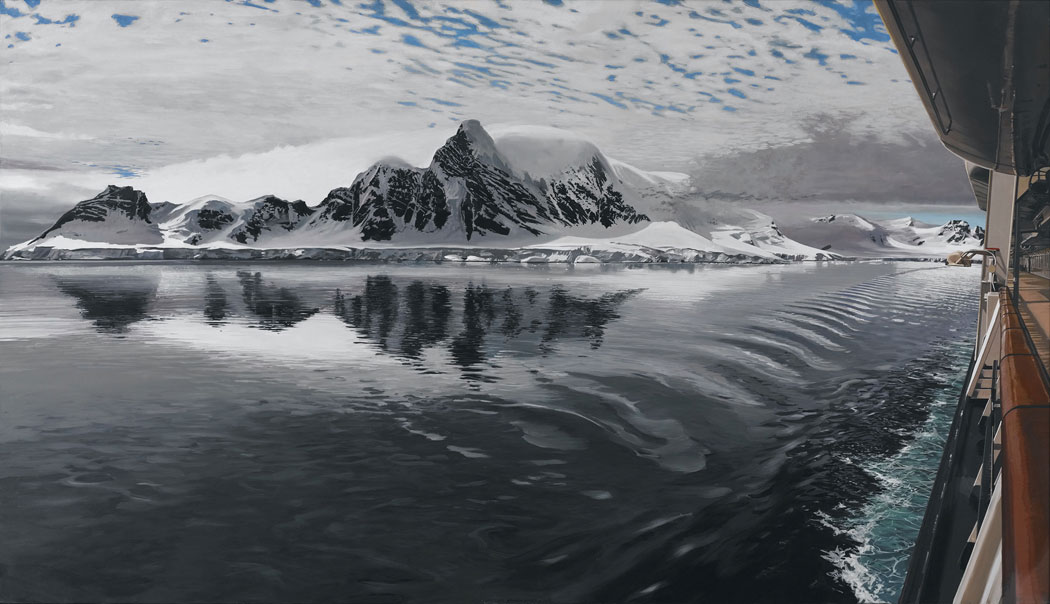

Instead, as seen in the exhibition “Richard Estes Realism” at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine through Sept. 7, Estes was one of a group of artists—including Audrey Flack, Robert Bechtle, Chuck Close, Robert Cottingham and Ralph Goings—who arrived at this aesthetic crossroads and pioneered what became known as “photorealist” paintings. Rather than painting, say, from direct observation of the world around them, they faithfully, fanatically reproduced photographs. Or at least that was the story.

Their mechanical look aligned with a machine aesthetic that came to the fore in the 1960s in reaction to Abstract Expressionism’s hyper-personal, improvisatory style and the macho cults of personality that arose around the artists. You can see this purposely impersonal, machine style in Minimalism—in Dan Flavin’s arrangements of glowing fluorescent lights and Donald Judd’s rows of identical boxes. It’s evident in Pop art when Roy Lichtenstein mimicked printing processes in his comic-book-inspired paintings and Andy Warhol “mass” produced photographic screenprints at his studio that he called the Factory.

For photorealists, playing at the idea of painting like a machine opened a legit, backdoor way to return to full-on realism. And suddenly, at least for a while, realist painting became glamorous again in the precincts of fine art. (It’s perhaps more than just a coincidence that at nearly the same time the American fine art world began to finally consider photography fine art.) In the late 1960s, Chuck Close, for example, began painting 7-foot-tall heads based on photos he took. He sprayed on the black and white paint smoothly with an airbrush, which added to the feel that it was printed by machine rather than painted by a person. For Close, it was a focus on the process of how he made his art, a focus on a set of self-assigned rules. “I wanted something very specific to do where there were rights and wrongs,” he has said, “and so I decided to just use whatever happened in the photograph.”

Estes's interest was more purely visual—the allure of gleaming surfaces. He found his signature style with paintings like his 1967 canvas “Bus with Reflection of the Flatiron Building.” It shows a blue car, with the iconic office tower reflected in its rear window, driving next to a bus. Estes loves to dazzle us with his skill at reproducing the complex reflections on storefront windows, or in this case the visage of the building and the bus twisting across the fabulously glossy car. But a forlorn loneliness pervades the picture—and can bring to mind the godfather of this sort of urban American realism, Edward Hopper. It comes from the way the sunlight—seemingly late day light—rakes across the bus and spotlights a lone man gazing out a back window. Time seems to have slowed down, though not quite stopped, and the city has gone silent to allow us to concentrate on this moment and this man, who perhaps disappeared down the street five decades ago.

That Hopper-like melancholy seems not to have interested Estes. For much of the next decade, he avoided depicting people. He painted shiny escalators, chrome diners, shop windows stocked with candies or bridal veils. His signature subject for five decades now is the picture windows of shops and diners reflecting the bustling city around them, sometimes seen head on, but often looking from the side, looking down the windows and down the street so that the reflections in the glass mirror and kaleidoscope everything around.

Estes’s paintings look like they’re strictly copied from photos, but his method seems to have often involved him beginning quite loosely, working out the placement of things in an underpainting done in acrylic, sometimes shifting things around somewhat to add more drama to his compositions as he moved into oil. He frequently combines scenes from multiple photos, which is why it’s been noted that people who return to Estes’s sites often can’t make a photo to exactly match his paintings. They’re convincingly, impressively exacting looking images that may not be exact.

The 1980s and ‘90s found him painting bridges across Europe and Japan. He likes to make the supports for the bridge or walls along the edge of the river bisect the painting—much as windowpanes bisect his street scenes. Estes’s split-screen effect makes it seem like we’re looking at two worlds, or two paintings in works like “View of Manhattan from Staten Island Ferry” from 2008. On the right is the sunny interior of the ship, nearly empty except for a woman sitting on a bench and another woman standing looking out the window in the distance. On the left are the Statue of Liberty and the New York skyline seen from the water.

Estes acquired a home in Maine in 1975—these days splitting his time between New York and Maine’s Mount Desert Island—but it wasn’t until the 1990s that Maine became a consistent subject for his paintings. He paints Mount Katahdin and its reflection in a lake, trails and a fallen trees in the woods of Acadia National Park, a woman and girl riding the water taxi to Mount Desert Island.

Part of how Estes makes his paintings feel photographic is the way he applies the paint with cool, flat, affectless brushwork, with little on-canvas blending and no painterly flourishes. It all feels natural in his images of shop windows, phone booths and cars of New York City, but it can feel stiff if you get close to his paintings of forests. And this is why, for all his compositional razzle-dazzle, I often find myself more admiring of his skill than moved.

Looking at five decades of Estes’s realism, what stands out is the sense of passing time, of how New York was, of how the city is now. In his 2005 painting “43rd and Broadway,” New York is still the gleaming storefronts and grids of skyscraper windows that he’s been painting since the beginning. But a man, in shadow, passes in front of a pair of parked police trucks. In 2010, Estes painted the glowing windows of New York’s Columbus Circle at night. It can feel by turns glamorous and ominous. The city is more moneyed and polished than ever, but new fears shadow the scene.

Like photos, Estes’s photorealist paintings become more fascinating as they age because the pictures are stocked with information about people and places since transformed by time. Call it the time capsule effect. A sense of what is gone and lost honeys the best of his paintings, of which there are many, with bittersweet nostalgia.

Greg Cook is co-founder of WBUR’s ARTery. Follow him on Twitter @AestheticResear and be his true friend on Facebook.

This article was originally published on September 04, 2014.