Advertisement

How Do We Honor Those Lost To AIDS? From The AIDS Quilt To New Memorials

It was June 1981. “My dad is a doctor,” Grace Ryder O’Malley says, “and he diagnosed one of the first cases the week before I was born in Provincetown.”

It was the dawn of AIDS. And the Massachusetts town—long a resort and haven for the gay community—would be one of the places most ravaged by the disease. “As it exploded, this was a place where people came and did try to seek refuge,” O’Malley says. “It’s still a place where people are coming.”

Which is why the seaside community at the tip of Cape Cod is planning to construct an AIDS memorial.

“It came out of this feeling that Provincetown had been so affected by HIV and AIDS, not only all the losses, but the caregivers and the people who are living with HIV/AIDS now,” says O’Malley, a member of the town’s Cultural Council, which is leading the effort.

After talk about a memorial for more than a decade in Provincetown, in July 2013, the town’s Board of Selectmen approved constructing a monument on a 15-foot square of lawn on the Ryder Street side of Town Hall. Now artists have until May 7 to apply.

“It is literally the geographic center of the town,” O’Malley says. “This is front and center. We’re proud of this.”

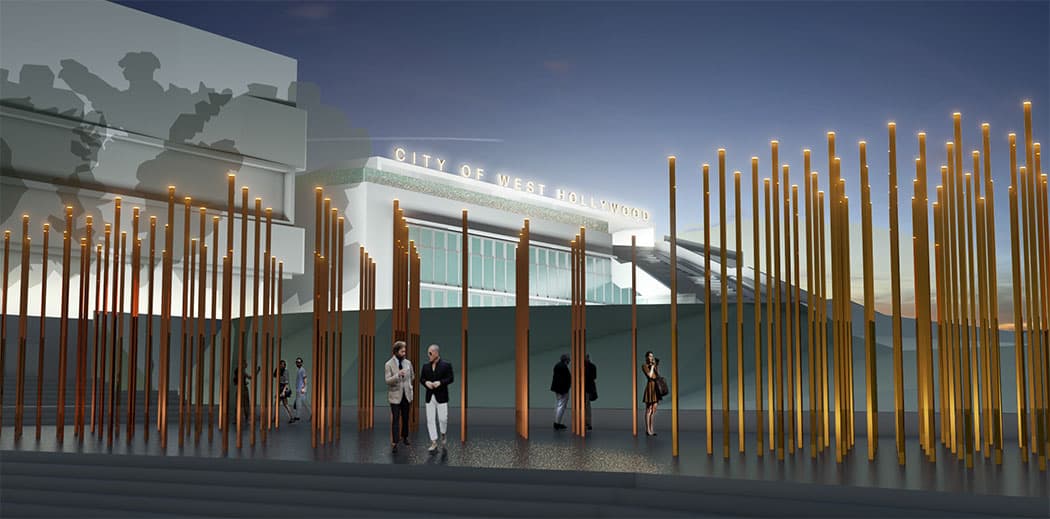

The Provincetown project is just one of the AIDS memorials being planned around the country. A New York City AIDS Memorial is in the works for a new park on the site of the former St. Vincent’s Hospital, which housed the city’s first and largest AIDS ward. In West Hollywood, California, they’re planning a memorial grid of 15-foot-tall rods or “traces” engraved with the names of the dead as well as caregivers.

What do we need from AIDS memorials? Why are we building them now? To answer these questions, I dug into their history—from the landmark AIDS Quilt to Boston’s “Medicine Wheel” to San Francisco’s National AIDS Memorial Grove—and spoke to people behind plans for the new ones.

“It’s about legacy. All of us who are in our 50s or older, who were there at the onset of AIDS are thinking about what our legacy will be,” says Julie Rhoad , executive director of The Names Project in Atlanta, the custodian of The AIDS Memorial Quilt. “People want to make sure that this can never be forgotten or dismissed.”

“I want people to feel the enormity of the loss of talent and love and family,” says Bobby Heller, one of the people planning the West Hollywood memorial. “For me, between 25 and 35 years old to lose 39 friends is ridiculous. This is not normal life. This is a completely unique and horrific situation. We want people to remember this. And to remember the caregivers who came to our rescue. And to remember this is how our community came together in a very strong and passionate way.”

The AIDS Quilt

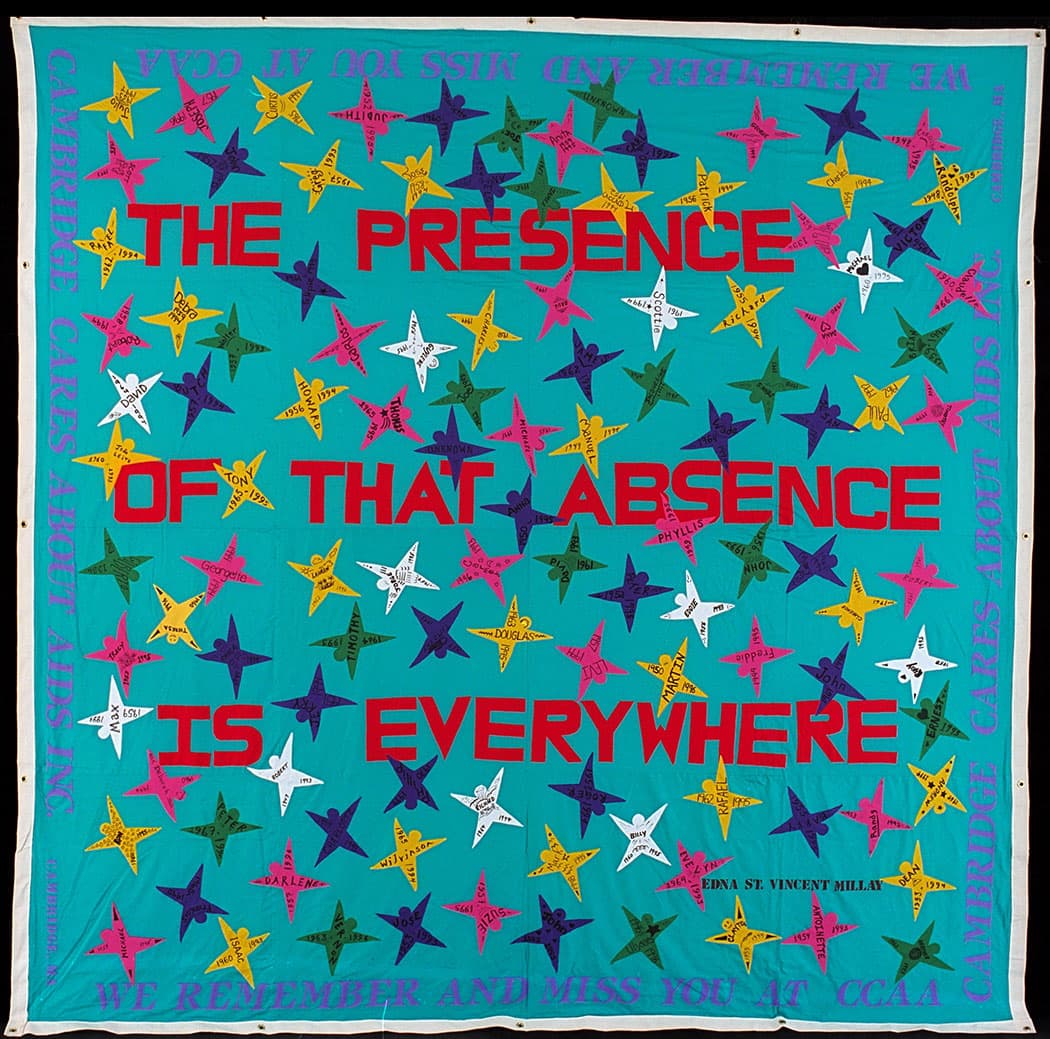

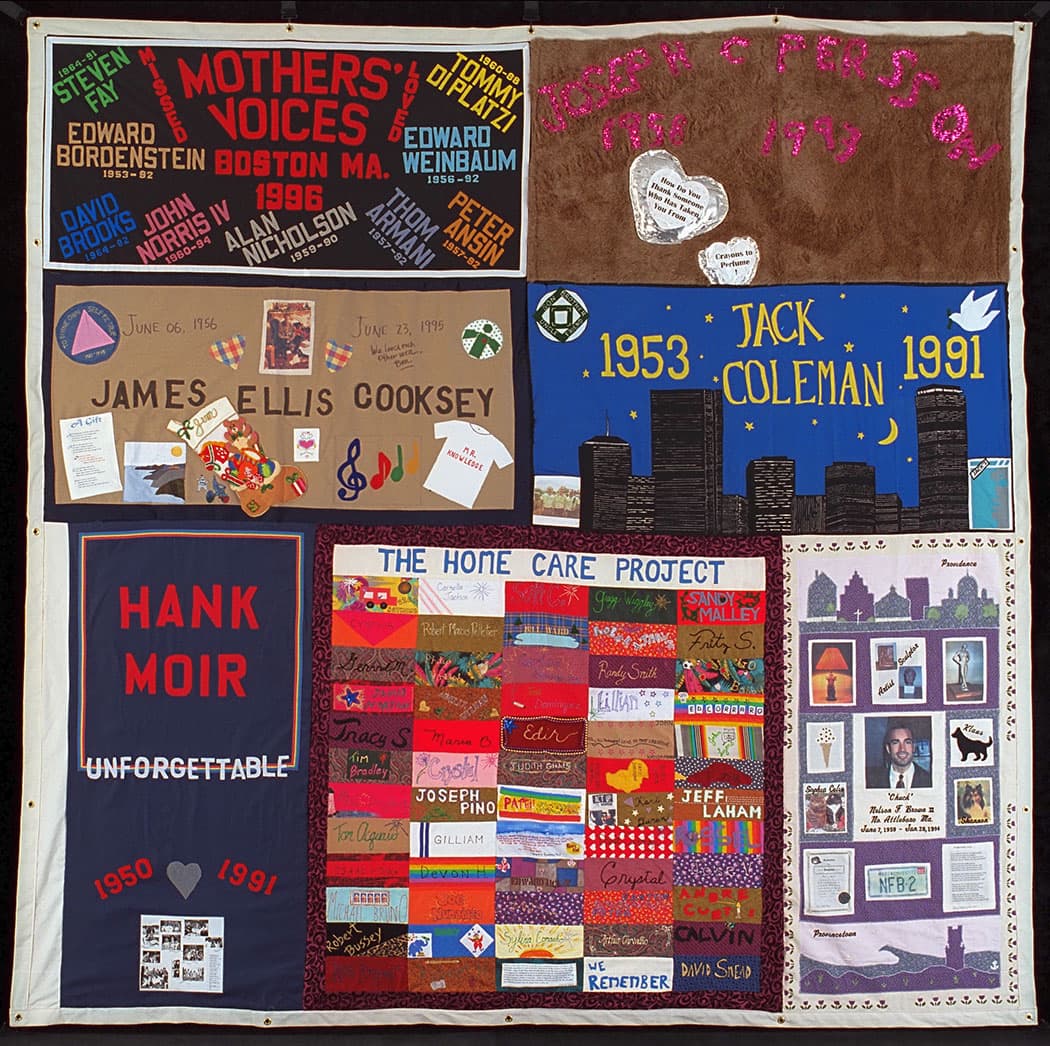

In spring 1987, Bay Area activist Cleve Jones—a friend and protégé of Harvey Milk, the pioneering gay San Francisco politician—began working with friends to assemble quilt squares. Each panel was 3 feet by 6 feet, the size of a human grave. Each was emblazoned with the name of someone lost to AIDS. And they put out a call inviting others to make more.

"My political cronies said it couldn't work,” Jones told The San Francisco Chronicle in 1996. "I always knew it would be successful.”

The idea had come to Jones during a 1985 march to remember Milk and San Francisco Mayor George Moscone, who were both murdered by a gunman at City Hall in 1978. Jones asked participants to carry signs featuring the names of San Franciscans who had died from AIDS. At the end of the procession, they taped the signs to the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building. The patchwork look reminded Jones of a quilt.

In June 1987, the first 40 panels of the AIDS Quilt were hung outside San Francisco City Hall. “We were founded to remember their names and to advance a movement,” Rhoad says. “We were founded by a group of grassroots activists to transform the conversation from statistics, the other, all the things that were driving the conversation in the ‘80s.”

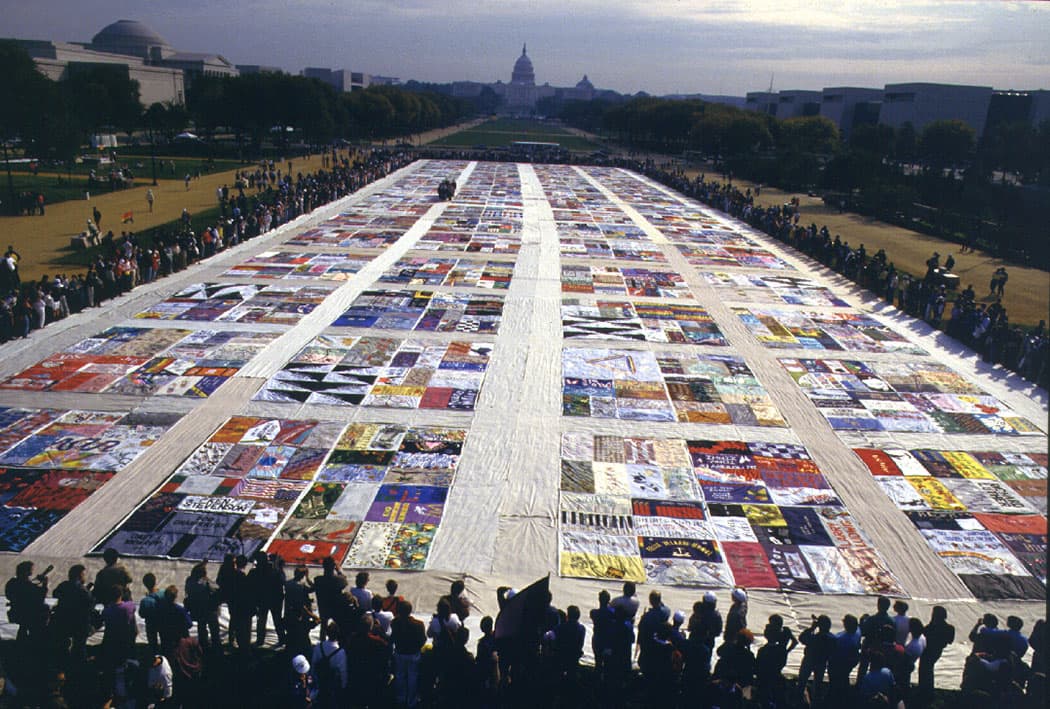

That October, the group spread some 1,920 quilt panels across the National Mall in Washington, D.C., as the nationwide AIDS death tally passed 24,000.

Many governments, social groups and religious organizations had turned their backs on those fighting for their lives—if not outright pillorying AIDS victims because of homophobia and racism. Which made the idea of a public, permanent AIDS memorial feel unthinkable in the 1980s. Which is what the activists were contesting by dreaming up the quilt.

The AIDS Quilt is a people’s monument. “It is literally the most democratic memorial I can think of. It’s made by the people for the people they love,” Rhoad says. It is handmade, soft, embracing, warm. Square by square it personalizes the staggering loss of a generation of people.

The quilt was stitched together via the do-it-yourself means that had become the primary way of operating for those suffering from AIDS and their loved ones after they realized that help was not coming from many of the usual sources of care. Instead they organized their own health care, housing, meals and mutual aid societies.

The ostracization of AIDS victims had pushed much mourning into private. “People were scooping up their family members and friends and taking them home in silence,” Rhoad says. The quilt was a way to join together publicly to heal, to insist they had nothing to be ashamed of, to shame society’s leaders into action.

“We thought we could end AIDS if we just got science and medicine and politics behind it,” Rhoad says. “Public health officials moved the meter … once politicians got pressured into helping, not abandoning a community, once people realized in some small way that their homophobia and stigmatizing this disease didn’t just kill gay people, it killed tens of thousands.”

Medicine Wheel

Each Dec. 1, since 1992, to mark World AIDS Day, Boston artist Michael Dowling has organized “Medicine Wheel,” a 24-hour community vigil at a circular art installation, newly created each year. In many ways, this Boston AIDS memorial reflects the early years of the crisis—do-it-yourself, temporary, funereal.

“My work is always based on something very personal,” Dowling says. “World AIDS Day is an opportunity for me to remember the loss of my partner, the loss of my father. … In healing is forgiveness and in forgiveness is letting go.”

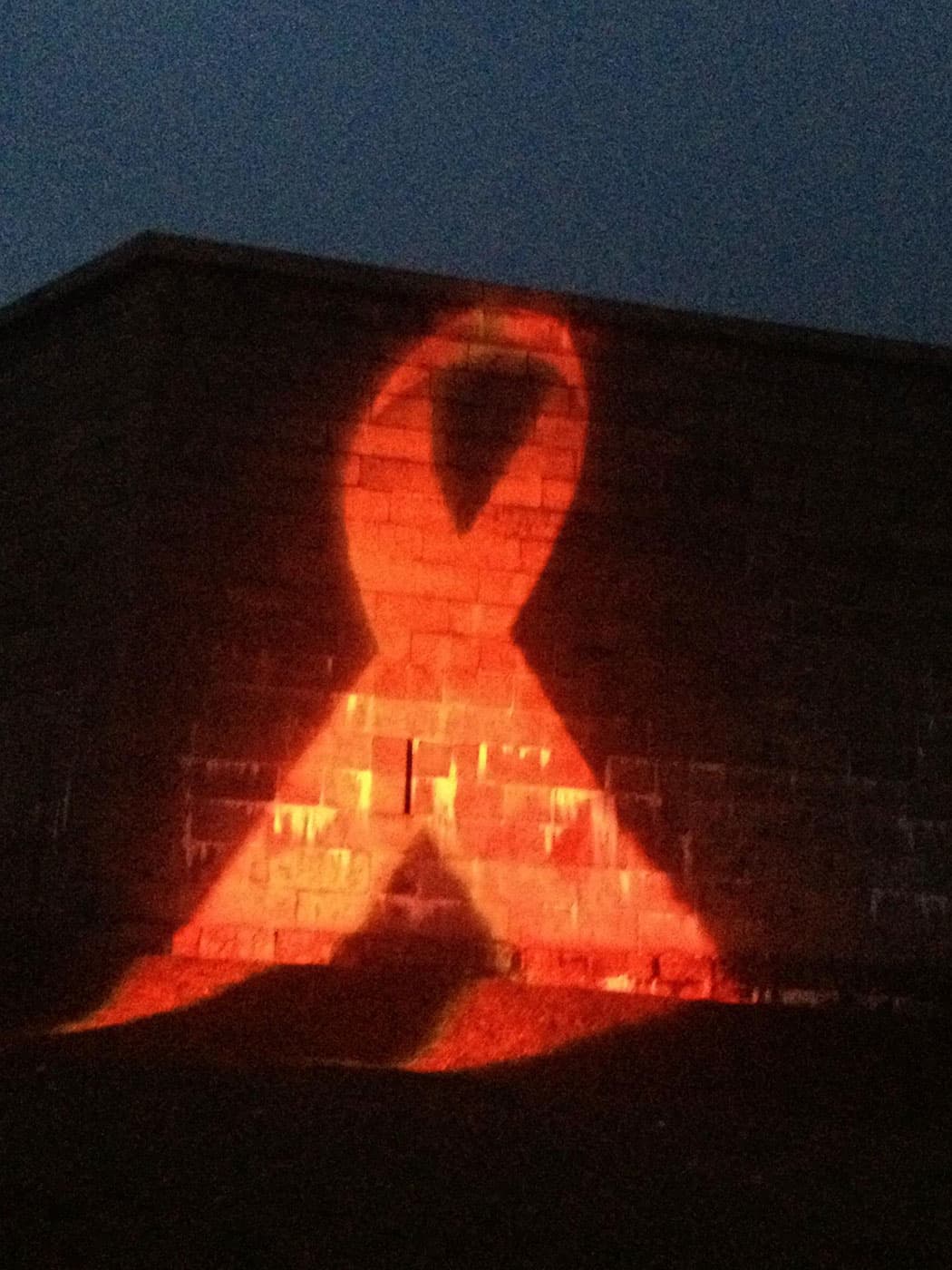

For many years, “Medicine Wheel” was held inside the vast cyclorama at the Boston Center for the Arts. But last December, it was held outdoors at Fort Independence in South Boston. The iconic red AIDS ribbon was projected onto the side of the fort. Coptic deacons said midnight prayer during a candlelight procession. Later Buddhist monks greeted the dawn with chanting. Some 16,000 offerings that had been left over the years—letters, jewelry, clothing, Mass cards, photos—were ritually burned.

“The power of really good memorial art is not a depiction of what happened,” Dowling says, “but to feel more human and more connected to other human beings.”

Dowling adds, “One in four of us died in Boston during those years. In P-town, I think it’s even higher. Part of this is recognizing that we all had value.”

“A lot of gay men my age are revisiting the grieving process and realizing the healing process has not happened,” says Dowling, who is age 60. “So much of what happened during the dying years of AIDS is things were not seen and things were not testified to. … What happened to our dreams? What happened to our hope? What happened to our future?”

Memorial Grove

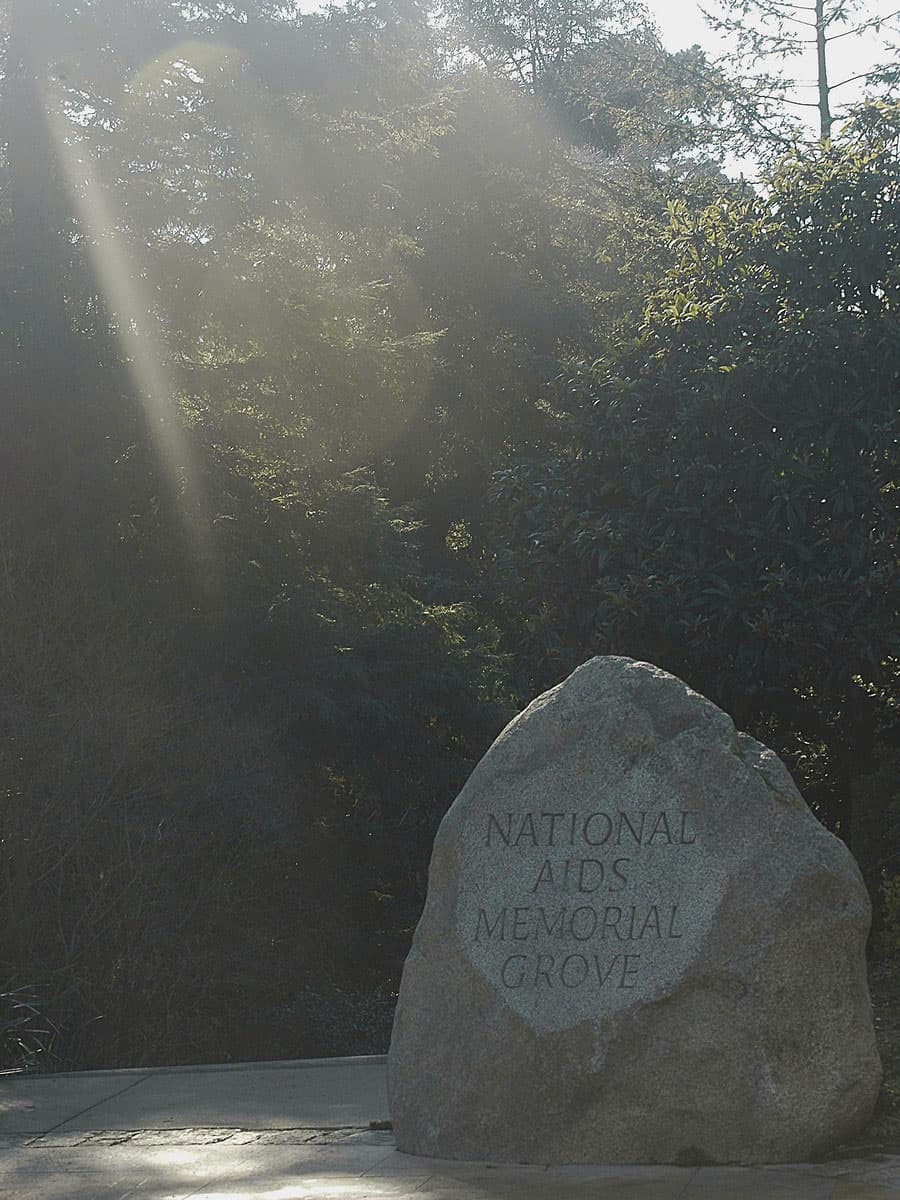

Around the time “Medicine Wheel” was being launched in Boston, a group in San Francisco was establishing one of the first permanent AIDS memorials in the country.

“We have yet to find any other memorial that was created in the middle of what you’re memorializing,” says John Cunningham, executive director of what is now known as the National AIDS Memorial Grove in San Francisco. “This brings such a dilemma to the process. … The grove was created 24 years ago when death was still so pervasive.”

Work began in 1991 to rejuvenate de Laveaga Dell, an overgrown 7.5-acre section of Golden Gate Park that the city donated for the memorial grove. They cultivated dogwoods, rhododendrons, magnolias and redwoods. At the grove’s heart is the “Circle of Friends,” featuring the names of some 3,000 people who’ve died from AIDS etched in stone, as well as the names of loved ones, care givers and donors.

The grove was declared a national memorial by an act of the U.S. Congress in 1996 —at a time when a new “AIDS cocktail” treatment was transforming AIDS from a death sentence into a manageable illness. The following year, AIDS fell out of the top 10 causes of death in the United States for the first time that decade, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, though tens of thousands of Americans continued to be infected annually.

“All soft and muted. There’s no bright colors, ensuring that the space is quiet and contemplative and restful,” Cunningham says of the grove. “You go through light and dark and then light. … It’s very much a metaphor for our journey through life.”

The third Saturday of each month from March to October is a community workday. “People came to remember,” Cunningham says, “but then it became clear really quickly that the power of what was going on was the healing of people connecting from going through the same experience.”

AIDS memorials across the country have taken many different shapes, but gardens have become the most prevalent way to remember the dead and honor the living. A modest AIDS memorial garden planted along an abandoned, out of the way stretch of railroad in Houston is said to have been begun in 1986—and may have been the earliest public AIDS monument in the U.S. There’s also the Garden of Peace and Love in Laguna Beach, California; the Living AIDS Memorial Garden in Charleston, West Virginia; and AIDS Remembrance Garden in Rochester, New York. There are AIDS memorial gardens in Las Vegas; Boulder, Colorado; Nerinx, Kansas; Lancaster, Pennsylvania; Clemmons, North Carolina; Wichita, Kansas; and Tampa, Florida.

A garden—specifically a grove—was the centerpiece of an early design for the proposed New York City AIDS memorial. The “Infinite Forest” would have been a triangular group of trees, fenced by mirrored walls creating the illusion of woods that went on forever. The plan now calls for the monument to be an angular, modernist 18-foot-tall shelter above a granite floor engraved with Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself.” It would serve as a gateway to a small park with a smattering of trees.

The popularity of memorial gardens is likely because they are a powerful metaphor for renewal. As Cunningham notes, they “create life out of death,” they give people a chance to come together “with the same sense of devastation and find healing in nature.”

The Last Panel

Some 13,712 people with AIDS died in this country in 2012, according to the most recent statistics available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And since the first cases appeared more than three decades ago, “approximately 658,507 people in the United States with an AIDS diagnosis have died overall.”

“Right now P-town has the highest incidence rate of HIV per capita in the state and one of the highest in the country,” says O’Malley in Provincetown. “It’s definitely something we’re still dealing with. It’s not in the past.”

The AIDS Quilt has grown to now honor some 96,000 people. Rhoad says, “We get a new panel almost every day.”

“In 1987, we received a single panel,” Rhoad says, “and all it says on it is, ‘The Last One.’ And within one of the letters it says, ‘When the last one is named, we will begin to heal.’ We’ve never sewed that in because it’s both a prayer and a promise.”

“Our job originally was to wake the world up,” Rhoad says. “Our job was to call on humanity to respond to this crisis with compassion and resolve. And our work today is one of trying to keep the pressure on, but it really has expanded to include prevention and care and to teach the generation to come. We believe the next generation is the one that will end AIDS.”

“The ideal monument will be the last one,” Rhoad says. “Our goal with the quilt is to be able to sew the last one in. We’ve been holding onto that last panel for nearly 30 years.”

Greg Cook is a co-founder of WBUR's ARTery. Follow him on Twitter @AestheticResear or on the Facebook.