Advertisement

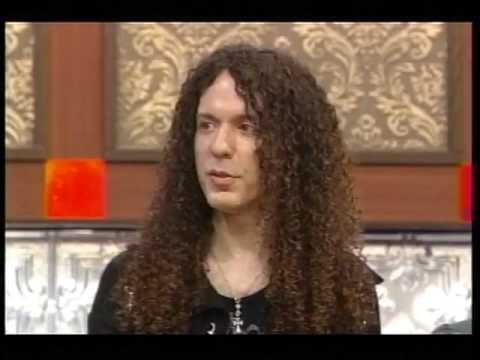

Megadeth’s Marty Friedman Left Heavy Metal Stardom To Become A Japanese TV Star?

There is a contradiction at the heart of rock ‘n’ roll as an art form: That even as it flaunts its rule-breaking live-for-the-moment attitude, successfully creating content within the form requires perseverance, dedication and the ability to convert countless hours of unending tedium into eventual moments of sheer excitement. To anyone who has seen years of their life sputter and crackle in the pyre of rock, one truth wills out to make tolerable the endless parade of horrible gigs, blown eardrums, bitter feuds and sad defeats: Dedication and discipline, focused on the purity of the music, is its own reward.

Journeyman metal guitar god Marty Friedman, whose solo band plays Brighton Music Hall on Sunday, Sept. 13, is one of those guys who casually says things like, “Work hard and you get lucky.” But for him, it was less about working hard than following the music, even if doing so meant making life decisions that, on the outside, might seem insane.

Consider this: throughout the 1990s, Friedman was the lead guitarist for LA thrash-metal behemoth Megadeth, experiencing a career zenith that saw him and his bandmates selling albums by the millions, taking Learjets and limos and generally living the rock superstar lifestyle. At the end of the decade, though, he quit his gravy train, packed up his things, and started again, almost at the bottom, in Japan, where he was a relative unknown.

“It was kind of like starting from scratch,” Friedman explains, on the phone from his Tokyo office. “Although I was known to some extent as an international musician, having toured here for many years, domestic fans [i.e. Japanese fans of Japanese music] don’t listen to international music. When I got the opportunity to play in front of those domestic fans, they didn’t know who I was, they just saw some longhaired American guitarist, so I had to win them over one at a time. It was a humbling experience.”

Friedman squeezed in our talk between business meetings and juggling press for his upcoming U.S. solo tour. It’s his first tour since leaving the States 15 years ago, fueled by the success of 2014’s “Inferno” (Prosthetic Records), his first solo release intended for an international audience since he moved to Japan.

Friedman’s name may not ring many bells in mainstream American culture outside of metal circles, but in Japan he is a bona fide pop celebrity, not just as a hotshot guitarist who has played on domestic pop hits (like the truly epic “Infinite Love” by the girl group Momoiro Clover Z, which hit number 3 in Japan in 2012), but as a television personality and media star. In the mid-‘00s, he hosted the “Mr. Heavy Metal” and then later “Rock Fujiyama” television shows, riffing on his hebimeta image for six seasons and creating an identifiable Japanese media brand that would launch him into the rarified world of being able to host cooking shows, weigh in on Japanese politics as a recognizable talking head, or judge variety shows for a domestic audience unfamiliar with the stadiums of American metalheads he spent decades playing for.

***

Friedman’s split from the Western world was not as sudden as it might have seemed to American metal fans at the time: his fascination with Japan was building the whole time he was in Megadeth. He first experienced Japanese musical culture when he toured the country with his pre-Megadeth outfit Cacophony, a late-‘80s twin guitar maelstrom that saw Friedman and fellow guitarist Jason Becker turn metal conventions upside-down with their twisting thickety riff mazes. Listening to what was big in Japan at the time, he found that the complexity of his style was not as unusual a thing in Japan. Returning often to Japan while in Megadeth, he continued to hear the country’s siren call.

“I heard Japanese music, popular music, and I thought, ‘I love this stuff. This is for me,’” he recalls. “Every time I would tour there, I was buying boatloads of CDs and listening to them everyday thinking, ‘This is where I belong and would love to play.’ I was way more inspired back then with what I was hearing here in Japan than what was happening in America.”

Advertisement

Friedman went so far as to teach himself Japanese via correspondence school, eventually becoming fluent enough to do Megadeth interviews in Japanese when they toured the nation. It dovetailed with his lack of enthusiasm with the music he was doing in the States. “I was burnt out; not on metal, per se, but on old-fashioned music, what was happening in the American charts, just the whole American music scene. I just wasn’t thrilled by it and, more importantly, didn’t know my place in it.” However, he definitely could see his place in Japanese popular music. “In America, pop is pop and metal is metal—but the thing is that heavy metal finds its way into pop over here. The first J-Pop artist that I worked with was Aikawa Nanase. She’s a pop singer, a huge mainstream star, but some of her songs are full of brutal metal. So I fit right in there.”

It was the first of a number of lucky breaks for Friedman: working with Nanase was crucial in establishing himself in a field that few non-Japanese musicians can infiltrate. “Working with her was liberating; we’d be working on one of her pop songs, and I’d be kind of holding back, and she’d be like, ‘Dude, metal it out, go for it, do what you want to do.’ I mean, here, pop music can go into metal at any time, and that musical freedom was so good for me, and definitely made my identity much more solid here in Japan.”

***

Friedman has long had a reputation for being a pretty off-the-wall guitarist—most metal fans of the ‘90s spent a fair amount of time scratching their heads at the ear-bending runs and melodies that would spring out of Friedman-era Megadeth songs. Exhibit A of this would be from 3:08 to 4:09 of “Tornado of Souls”, from 1990’s “Rust In Peace,” where a carefully orchestrated series of gorgeous axe wails morphs, crescendo-like, into the frantic garble-skronk of six strings being tossed into a blender. Friedman attributes his style to a youth spent voraciously consuming disparate musical influences.

“It got to the point, when I was a teenager,” he says, “where all the good guitarists were learning the same things: Jeff Beck, Al Di Meola, etc. They all did the same things. I did too, to a certain extent, but I started to realize that I wasn’t as good as the other guys, I couldn’t do that stuff, because I didn’t care about that progressive stuff. I had started to find music from China, music from Japan, from India, Persia, Middle Eastern music. I really connected to the melodies from those sources much more than the progressive jazz all my peers were getting into. So while they were trying to learn Mahavishnu Orchestra, I’d be picking out violin phrases from some Iranian cassette tape that I couldn’t even read.”

Of course, Friedman was also inspired to play rock in the first place by having seen Kiss at a young age, so the urge to expand his horizons was fighting for his attention with his desire to rock out and make a spectacle. These two urges might not fit within the somewhat puritanical confines of American metal’s orthodoxy, but in Japan being showy and visual whilst also being musically polymorphous is just standard operating procedure.

Friedman’s Japanese journey has also meant ditching the heavy metal tendency to shun anything having to do with mainstream pop culture. “You know, I was never a ‘metal or die’ guy, although I totally understand and respect that position. But I personally never bought into that—I always thought, ‘If there is something that I want to do, I want to do it,’ whether it’s regarded as cool, or mainstream, or whatever. I was into that metal purity thing when I was 14, and I get it, and it’s important. But I wasn’t that guy once I hit 18 or 19. Some things that I do are quite mainstream and I don’t really have any problems with that.”

In a sense, Friedman’s attitude, which our Western sensibilities might read as pursuing fame at any cost, is really about a disciplined focus on music, the music that Friedman wants to make, no matter where it takes him. As a guitarist in a platinum-selling stadium-hopping band in the 90s, he spent countless hours of downtime doing nothing but preparing for the next show or album or tour. As a multi-faceted Japanese music personality, his every waking second is spent fitting his musical talent and his natural enthusiasm for it into an ever-shifting series of projects that can see him working on a theme song for a TV show one day and plying an auditorium full of metal fans with strange original sounds the next.

“Part of it, for me, is that once I got to Japan I never thought, ‘Oh wow, this isn't gonna work out,’” he says. “I was fortunate that I started to go in the direction I wanted to go in when I moved here, working with a famous J-Pop artist and getting my face known in the domestic scene. But once television started to happen, I could do anything that I wanted to do. It’s been hard work, don’t get me wrong, absolutely the hardest work that I’ve ever done in my career by far, but I’ve had a lot of dreams come true because of it. I’ve been fortunate to have situations that allow me to work hard. In a sense, I’ve luckily been too busy to ever really stop and think, ‘Maybe I should go back.’”