Advertisement

Were Those Black ‘Servants’ In Dutch Old Master Paintings Actually Slaves?

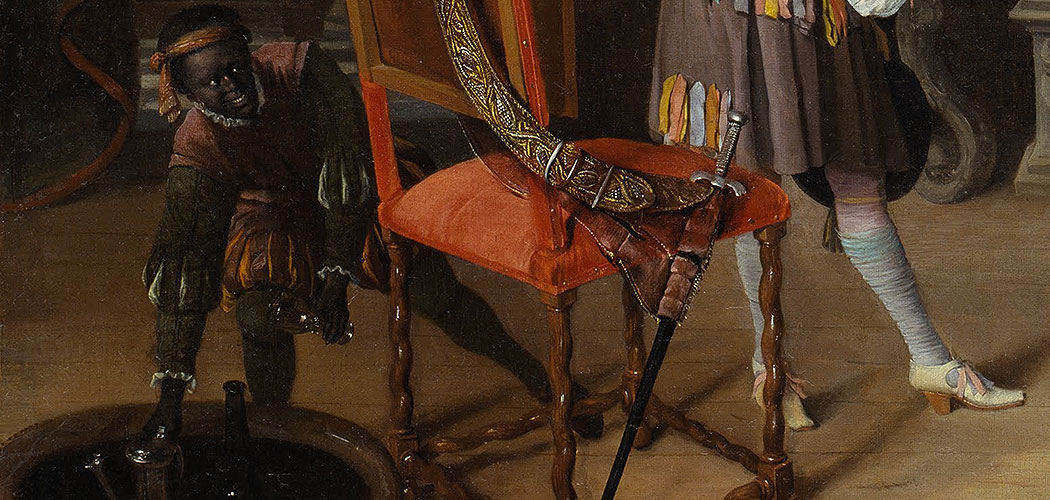

Who was the black man standing at the left of the 350-year-old painting? It depicts a Dutch family—the father, a wealthy brewer, leaning over the back of a chair to watch his grown daughters make music, playing a harpsichord, strumming some sort of guitar. Everyone in the painting is white except for the black man, with a glass in his hand, reaching down to a jug sitting in a tub, a cooler, on the floor. He's depicted almost like a dark shadow and he smiles wide, like a caricature.

The scene is titled “Fantasy Interior with Jan Steen and the Family of Gerrit Schouten." The Dutch painter Jan Steen painted the canvas somewhere around the year 1663. It hangs in one of the first rooms of the exhibit “Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 18.

“Seemingly every detail alludes to Schouten’s aristocratic aspirations,” a sign explained, “from the tapestries lining the back wall and the fanciful harpsichord to the presence of a black servant.” The sign seems to say that the brewer’s aspirations were demonstrated by what he owns (at least in this “fantasy”): tapestries, a harpsichord and … a black servant. I wondered: Was “servant” a euphemism? Was this black wine steward actually a slave?

Looking for People of Color in Western Art History

One of the things I sometimes do when I wander museum galleries of Western art is look for people of color in the “old master” paintings. In American cultural memory—well, in white American cultural memory—the “old masters” were white guys in Europe some centuries ago who painted white folks. But people of color are there in these artworks—somewhat infrequently and, as in the case of Steen’s “fantasy,” often not prominently—but it’s not hard to find them if you keep your eyes open.

I’m not alone in this search. Since 2013, Malisha Dewalt has been collecting images of “People of Color in European Art History” in her in her Tumblr blog of the same name. And her project has echoes of the landmark research project that Houston art collector and philanthropist Dominique de Menil launched in 1960 to document portrayals of blacks in Western art as a counter to what she called “an intolerable situation: segregation as it still existed in spite of having been outlawed by the Supreme Court in 1954. Many works of art contradicted segregation. A sketch by a master could reveal a depth of humanity beyond any social condition, race or color. So why not assemble these artworks in an exhibition or a book?” It turned into a monumental series of books titled “The Image of the Black in Western Art,” that began being published in the 1970s—and has been expanded on and reissued via Harvard University since 2010.

Advertisement

I’m not anywhere in their league, but I still happened to be on the lookout for portrayals of people of color when I visited “Class Distinctions,” the museum’s survey of 17th century Dutch art. In part, because the exhibition’s theme of how class was portrayed in old master painting seemed to call out for it.

The MFA’s website explains: “The show reflects, for the first time, the ways in which paintings represent the various socioeconomic groups of the new Dutch Republic, from the Princes of Orange to the most indigent.” A sign at the beginning of the exhibit says: “We invite you to think about class distinctions then and now and to revel in the beauty of the finely crafted paintings that represent a past culture not so very different from our own.” What could be a more revealing of the class distinctions in the 17th century Netherlands than portrayals of race?

Among some 75 artworks in the exhibition, I noted three paintings including black people, all in the first gallery, which was devoted to depictions of "the political and social elite—princes, nobles, regents, and merchants, the Dutch Republic’s 1 percent.” These people of color were not the 1 percent, of course. In addition to the brewer’s “servant,” in Jan Verkolje’s 1674 portrait of Delft city councilor, alderman, and bailiff Johan de la Faille, I found a black man deferentially stooping over, keeping hold of the leashes of the white man’s hunting spaniels. A sign explained, “Verkolje presents his sitters with indicators of their status: in Johan’s portrait, a young black servant and the accoutrements of the hunt.”

And there was a “black page” (according to the museum sign) wrangling a horse in the background of Jan Mijtens’ 1650s portrait of prominent lawyer “Willem van den Kerckhoven and His Family.” The painting’s “considerable size, his family’s fine clothing, and the presence of a black page in the middle ground all signal the man’s prosperity,” the sign informed. Again that curious formulation of the sentence—the man’s wealth is signaled by his fancy possessions—and a black man. Was the black page one more of van den Kerckhoven’s possessions? Was he, were all these black “servants,” actually slaves? It was a mystery that this MFA exhibit about “class distinctions” didn’t answer. I set out to find out.

The Golden Age Of Dutch Slavery?

These days, the 17th century is often called the Netherlands’ “Golden Age.” The Dutch then were a major seafaring power with maritime trade fueling fortunes back home, which in turn funded the great paintings. Heard of New York City? It was controlled by the Dutch and called New Amsterdam until 1664 (right about the same time Steen was painting his fantasy) when the English seized the city. One of the maritime businesses that brought wealth to the 17th century Dutch was shipping slaves captured in Africa to the Americas.

“The Dutch wrested control of the transatlantic slave trade from the Portuguese in the 1630s, but by the 1640s they faced increasing competition from French and British traders,” according to a U.S. National Park Service research of “African American Heritage & Ethnography.” “England fought two wars with the Dutch in the 17th century to gain supremacy in the transatlantic slave trade.” Between 1651 and 1675, the Dutch were only outpaced as slavers by the English, sending some 64,800 people into slavery in the Americas, according to the Park Service, referencing groundbreaking research done into slave trafficking by a team lead by David Eltis and Martin Halbert.

Which might seem to support the idea that the black “servants” depicted in these 17th century Dutch paintings were actually slaves.

But then there’s this: “Slavery was technically illegal in the Netherlands at this time, as it was throughout Europe, but the situation was still porous,” explains Sheldon Cheek, assistant director of the Image of the Black Archive & Library at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center. “Often, Africans would be brought into the Netherlands by means of the Dutch slave trade, presented as ‘gifts’ to the wealthy.”

“The young black people seen in the exhibition … served within noble households as signs of prestige and ornamentation which, like fine paintings, furniture and the like, could only be afforded by the privileged classes,” Cheek writes via email. “… As these black servants grew up, their duties within the household often changed substantially. Sometimes they were charged with duties of exceptional authority such as bookkeeping and other types of household management, or as musicians, horse grooms, hunting companions, or as lavishly dressed troops featured in grand ceremonial pageants. In other cases, they were sent to other wealthy, noble, or even royal households as tokens of esteem or self-promotion.”

No Way To Determine Their Status

For more help determining whether the black men in the paintings were free servants or actually slaves, I turned to Ronni Baer, the Museum of Fine Arts' senior curator of European paintings, who organized the exhibit. “There is no way to determine the status of the black people seen in the paintings you mention (nor do we have records of the servants employed by these specific sitters)," she writes via email. "One important point to note though—the Dutch slave trade brought slaves to the New World, not to Europe. However, the slave trade did contribute to the wealth of the upper class in the Netherlands, and it is possible that the men depicted were either slaves or in the Netherlands as a result of the country’s involvement in the slave trade.”

How might the black men depicted in these paintings have ended up in their positions? Baer says they could have been slaves that Dutchmen residing in the Americas brought to the Dutch Republic. “In this case, the tendency seems to have been toward manumission upon arrival in the Republic because the institution of slavery was forbidden on sovereign Dutch territory (though NOT in the New World colonies),” she writes.

Or they might have been “free blacks” who settled in the Netherlands, Baer says, and found employment by Dutch upper classes. Or, she says, they could have come to the Netherlands “as black slaves of Portuguese Jews who resided in the Netherlands (largely a factor in the first part of the seventeenth century); since prohibitions on slavery in the Dutch Republic also had a religious component forbidding Christians from being enslaved, the exact status of these individuals is a bit murky (they were often, like their masters, buried in the Jewish cemeteries); it is not entirely clear whether the prohibition on slavery extended to them.”

But even if the black men in the paintings were free, how free were they? Cheek notes: “The unenslaved status of the African servants begs the question of their self-agency in Dutch society. Their relatively comfortable existence within the ambient of the elite classes tended to keep them within its orbit, but what if they wished to leave it? … Presumably this significant degree of change in the circumstances of life would have been legally permissible. There are probably recorded instances of such acts of self-assertion in the Netherlands during this period. Examples certainly exist in contemporary France and England. In any case, leaving the relative security of the wealthy household for the vagaries of a more independent life would have presented its own kind of challenges. The reality of such changed conditions of life, however, seems to lie outside the pictorial record of the Dutch world.”

Discuss this article with Greg Cook, co-founder of WBUR's ARTery, on Twitter @AestheticResear or on the Facebook.