Advertisement

Modernist Cute: Mary Blair’s Art For ‘Dumbo,’ Golden Books, ‘It’s A Small World’

Remember that heartbreaking scene from Disney’s 1941 feature “Dumbo” when the little elephant visits his mom in jail and she reaches her trunk through the bars to caress her baby? How about Disney’s 1950 film “Cinderella,” when birds and mice dance through the air as they help Cinderella sew a gown to wear to the prince’s ball? Or recall the moment in Disney’s 1953 film “Peter Pan” when the children soar with Peter Pan around the top of London’s Big Ben?

These were all ideas that Disney artist Mary Blair helped dream up. In a large company team, for which Disney himself took much of the glory, she was one of the most iconic artists. Then she left the studio in the 1950s to work in advertising and illustration, including producing Golden Books like her 1951 children’s picture book masterpiece “I Can Fly.” Then Disney himself recruited her back as the lead stylist behind Disneyland’s famous “It’s a Small World” boat ride.

Blair’s name isn’t well known outside the worlds of animation and illustration, but her crisp, flat, graphic, cute midcentury modern style—showcased in the exhibit “Magic, Color, Flair: The World of Mary Blair,” at The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst through Feb. 21—is one of the major influences in these fields today. A couple of examples: Title sequences of Pixar films are in her debt, as are many of newly published Golden Books.

That dazzling and inspiring Mary Blair may never have emerged if she hadn’t talked her way onto a 10-week trip Walt Disney took with core members of his studio to Brazil, Argentina, Peru, Ecuador, Guatemala, Chile and Mexico in 1941. “She heard that he [her husband, Lee] was going to go to South America with Walt and she had the gumption to go in and ask if he would take her too,” New York animator, animation historian, and exhibit organizer John Canemaker tells me. Disney added her to the travel roster. When she returned, Blair was a new artist.

Mary Blair and her husband Lee had aspired to be painters, fine artists. But struggling to make ends meet during the Great Depression, they took jobs in Hollywood’s growing animation industry. Lee found his way into the Disney studio in 1938, then helped Mary land a job there in 1940, where she sketched that tragic prison visit for Disney’s 1941 flying elephant film “Dumbo.” But Mary Blair quit Disney after two years, feeling frustrated by the confines of the studio production process, and briefly pursued illustration until she got Disney to include her on that trip.

The studio’s 1941 Latin American tour was a Franklin-Roosevelt-administration-funded “Good Neighbor” trip, part of a hearts-and-minds campaign aimed at fighting the spread of Nazism and fascism in the Americas. After the great critical and commercial success of Disney’s first feature-length animated film “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in 1937, World War II cut into the studio’s audience in Europe and the studio’s following films lost money. Then many animators went on strike seeking better pay. Walt Disney felt betrayed. The trip, for him, was an escape from these troubles as well as a needed infusion of government cash, including a government guarantee of basic financial returns on the two Latin-American-inspired films that resulted.

Blair’s style had been sturdy, fluid, and earthy—lots of browns and blues and grays—before the trip. In Latin America, she inhaled the culture, jotting down telling details of how people dressed, painting evocative scenes of a man loading up a llama or a woman carrying her baby and a basket of fowl to market. Blair breathed in the tropical scents and was dazzled by the bright colors. At times, her new paintings and drawings seemed to glow like neon—inspiring the flowering jungle she imagined a little pink train bouncing through for the 1944 film “The Three Caballeros."

“I’ve been down to Rio three times and there is a difference in feel down there, in the colors, the smells, the tastes. I think they were all inspired by it. She was particularly inspired by it,” Canemaker says. “It kicked off like a stick of dynamite.”

Blair abandoned her earth-toned realism for a Technicolor modernist flatness honeyed with folksy, faux naïve charm. “Walt noticed big time and she became his favorite artist at the studio,” Canemaker says in the 2008 documentary film “Walt & El Grupo.” “He brought her along on projects for the next 10 years.”

Blair returned to the California studio as an “inspirational sketch artist.” “They were people allowed their head,” Canemaker says. “She would come in at the very early part of things.” She contributed to the two films that came out of the trip—“Saludos Amigos” (1942) and “The Three Caballeros” (1944). Then she designed crisp winter scenes and heavenly apple orchards for “Make Mine Music” (1946) and a demonic Headless Horseman for “The Adventures of Ichabod and Mister Toad” (1949). Blair’s major contribution to the films? Canemaker says, “That sensuous look that comes in the 1940s.”

Meanwhile the Blairs left California for New York. There Lee started a company to produce television commercials and educational and industrial films. Walt Disney was so devoted to Mary Blair’s work that he took the rare step of keeping her employed by the studio even though she was a continent away from the rest of his crew. Walt occasionally visited. And the studio would fly her back and forth for major meetings.

For “Cinderella” (1950), Blair painted a scene of birds helping her make a gown for the ball, holding up the pink dress in her attic room. Another painting captures Cinderella’s dramatic flight from the ball as her white pumpkin carriage races home through blue trees that seem alive with her anxieties as the clock strikes midnight.

For “Alice in Wonderland” (1951), Blair painted the girl falling down the rabbit hole and spying through blue and purple trees of a Technicolor forest to a cockeyed, green house. Her sketches for “Peter Pan” (1953) all have a dreamy, nocturnal feel. She was a master of mood.

But her flat, graphic modernist style clashed with the Disney studio’s trademark fully-rounded, “illusion of life" characters. Canemaker says, “Walt championed her constantly. He kept saying, ‘Get Mary into this.’” Her contribution, he adds, was “taking stylized characters and giving them emotions that are believable. But that wasn’t Disney’s style. To reveal itself as a cartoon was a no-no.”

Mary Blair left the Disney studio again in 1953. “I think she wanted to do more on her own. There was no animosity back and forth,” Canemaker says. “There’s correspondence about him trying to get her to work with the Metropolitan Opera.”

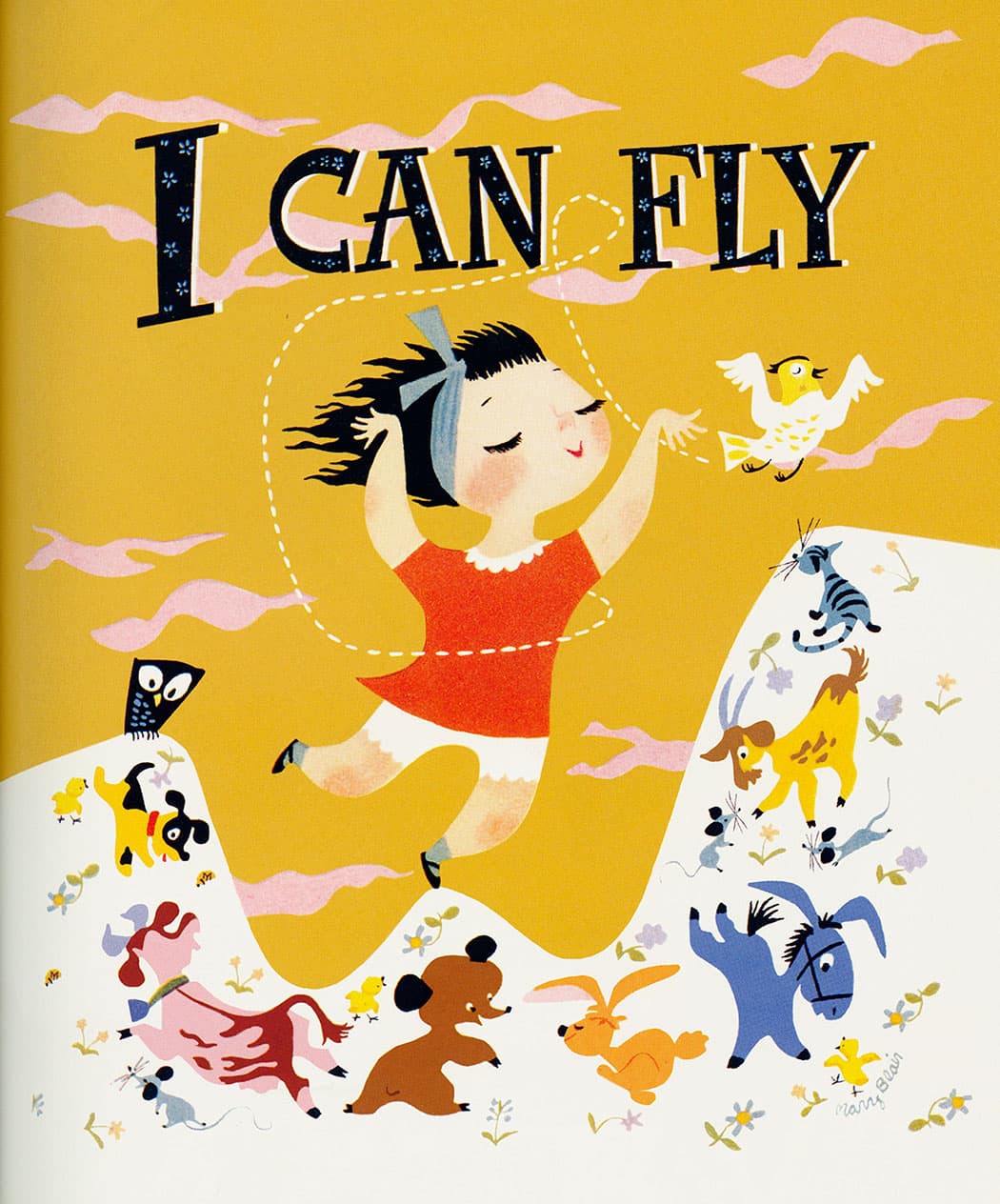

Blair had begun illustrating children’s books with 1950’s “Baby’s House” (words by Gelolo McHugh) and her 1951 masterpiece “I Can Fly” (words by Ruth Krauss), both published by Golden Books.

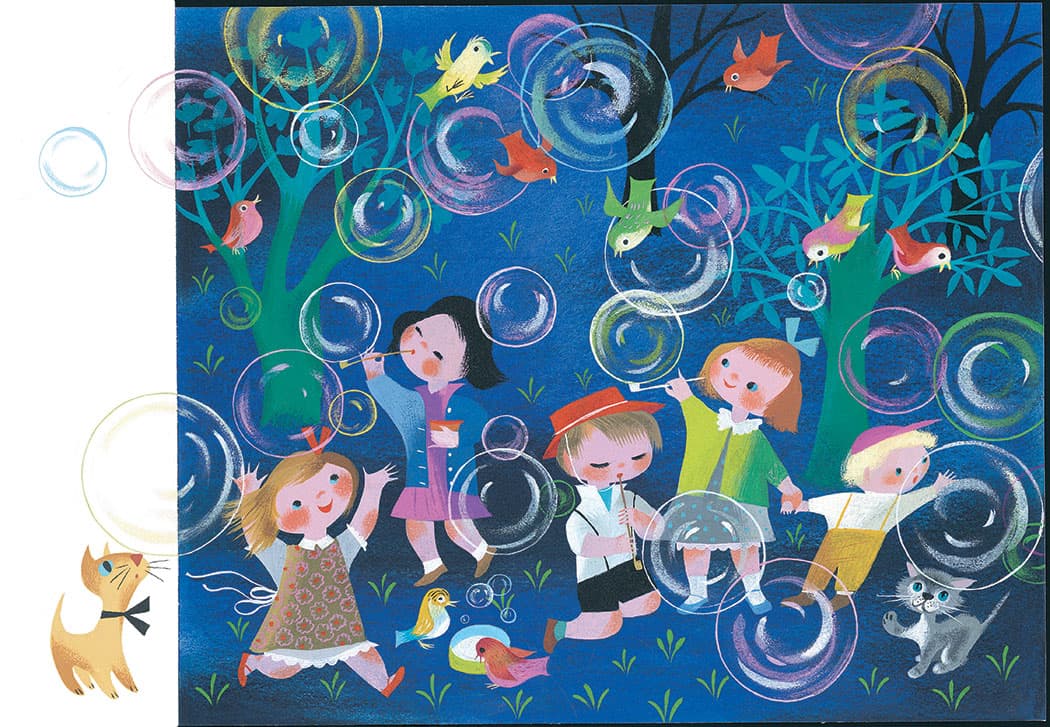

“I Can Fly” celebrates imaginative play with a girl who squirms like a worm, hops like a rabbit, swishes like a fish. The kids Blair painted are designed super cute, with big heads and large eyes. Her story sketches for Disney films had been loose and fluid, driven by action and mood, but left unpolished. For the books, her style becomes more stylized, precise and detailed. Compositions crackle with calligraphic lines dancing atop patterns and flat shapes of color. The children’s books open up a whole realm of wonder and joy and cute.

By then, Blair was the mother of two young sons. She created scarves and dresses for Lord & Taylor, designs for Radio City Music Hall holiday spectaculars, paper sculptures for the Bonwit Teller strorefront windows on New York's 5th Avenue, television commercials for toothpaste and ice cream, illustrations for greeting cards, and advertisements for Nabisco, Johnson & Johnson and Maxwell House Coffee.

But Walt Disney still wanted to work with Blair. In 1963, he approached her to help with a boat ride he was developing for the United Nations Children’s Fund pavilion, sponsored by Pepsi, at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. “It’s a Small World,” as the iconic ride came to be known, was a nuclear age call for world harmony and peace.

It is in many ways a culmination of what Blair began in Latin America—part modernist, part exoticizing, all cute. Her sketches show kids of the Pacific islands riding a dolphin, happy tots atop the Leaning Tower of Pisa, a pair of giraffes twisting their necks together romantically to form an arch over the boat channel. Her painted panorama of Europe shows the Eiffel Tower, a Dutch windmill, a Greek temple and Russian onion-dome buildings fitting together like a geometric puzzle. Others, of course, helped, but the look and feel of the ride—the cute children, the stylized flat scenes, the brilliant colors—is Mary Blair at her peak. The effect is like floating through one of her children’s book illustrations.

After the fair, Blair helped adapt the ride when Disney brought it to Disneyland (see Blair present the facade design for the theme park version in the video above), which he’d debuted in California in 1955, and create a second version for Disney World, which opened in Florida in 1971. Walt then hired Blair to design ceramic tile murals for a children’s section of a UCLA health center, for Tomorrowland in Disneyland, and for Disney World’s Contemporary Resort Hotel.

But the end of the tale is sad. After Walt Disney died 1966, Blair found herself without a champion within the studio and her opportunities there dried up. Meanwhile Canemaker reports in his 2003 book “The Art and Flair of Mary Blair: An Appreciation” that “Lee’s and Mary’s alcoholism” and huge medical bills racked up by “their eldest son’s emotional difficulties and subsequent hospitalization on the East and West coasts” lead to a personal and financial collapse. “I think they needed money to help their boy,” Canemaker tells me.

By 1970, they sold Lee’s production company and their Long Island home and moved to Soquel in northern California. Mary Blair struggled to find illustration work. Canemaker says a Blair friend “told me she was rejected by some art directors in San Francisco who told her her work was not modern enough.” Mary Blair, who'd brought so much dazzle and joy to the world, died of a cerebral hemorage on July 26, 1978, at age 66.