Advertisement

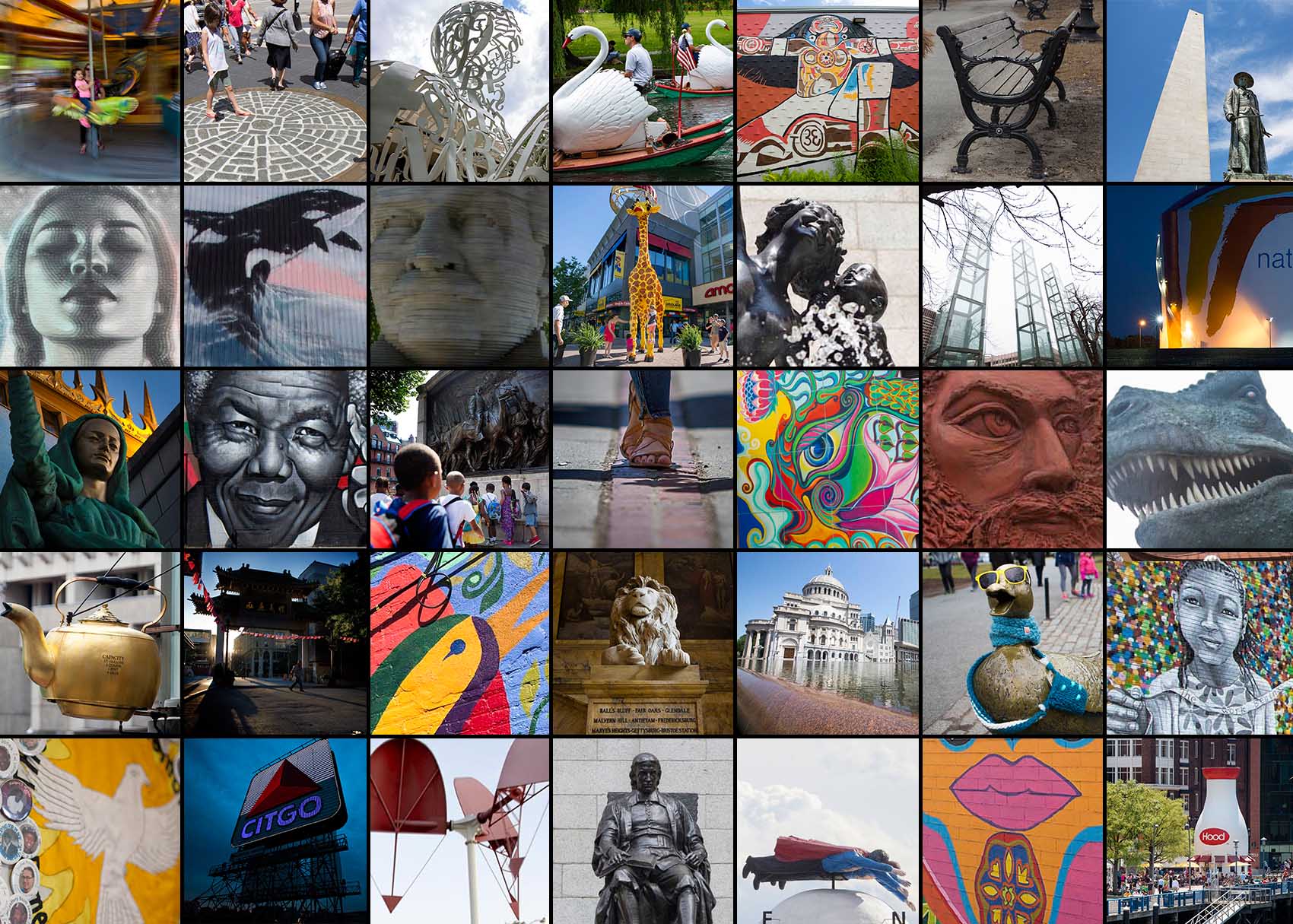

The 50 Best Works Of Public Art In Greater Boston, Ranked

Resume

In the past few years, excitement has been growing around Greater Boston about new possibilities for public art after a string of spectacular temporary projects — JR’s mural of a man standing on a raft wheatpasted onto the side of the (former) Hancock building, Janet Echelman’s glowing rope web suspended over the Rose Kennedy Greenway, Amanda Parer’s giant inflatable rabbits at Lawn On D and graffiti stars Os Gemeos’ giant painting of a cartoon guy at Dewey Square.

As these projects have embraced more delight and daring, I’ve been thinking about the long-term public artworks around here.

Former Boston Globe art critic Sebastian Smee has called our community’s collection of public art “frankly mediocre” and “relentlessly conservative.” Globe columnist Yvonne Abraham has lamented our “stodgy legions of bronze figures depicting politicians and sporting or other heroes.” Boston has some of the greatest 19th century bronze monuments in the nation, but overall, the collection is seen as too white, too male, too bronze, too dated, too dull.

This ranking of public art around Greater Boston is an attempt to reassess what we have, and to make a more full accounting by acknowledging the best pieces in our downtown parks and government plazas — while looking beyond, out into our neighborhoods and suburbs.

This list adopts a more expansive definition of art — accommodating “fine art” sculptures as well as landmark signs, graffiti, dinosaurs, conceptual art, psychogeography, secrets and surprises often left out of other lists. There are familiar stories here, but also stories rarely told. Exploring our community’s public art this way, you get a deeper vision of what we have, of the rich histories of our many, diverse communities, of different possibilities already (if perhaps tentatively) being explored.

How does one begin to rank the area's best public art? My criteria include aesthetics (beginning with beauty, but more than that), pleasure, meaning.

How does the artwork represent our history and traditions, the diversity and accomplishments of all our neighborhoods? How does it reveal how Boston has changed, is changing? Is it fun? Does the artwork make its site better? Have we embraced the artwork and made it our own? (For example, the way people play on and dress up the Public Garden ducklings.) How does it embrace the public part of public art?

My research has involved digging into history as well as conversations with artists, public art advocates and architects. But, in the end, it’s rooted in years of walking our streets as a critic, an artist and a neighbor.

Of course, these rankings, like any rankings, are ultimately subjective. This list represents my favorites. Today. It’s meant to be the beginning of a discussion about what we value in public art here and our vision for where we’d like public art to go.

So please let us know what you’re happy I included, what you’re sad I overlooked, what should have been ranked lower, what should have been ranked higher. And please let us know (in the comments, or on social media using #wburpublicart) about your own explorations of our community’s public art.

Scroll through the entire list below, or use the links to jump to a section. (For an interactive map of all the works, click here.)

50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-1

50. “Swimming Cities” mural by Monica Canilao, 2015

On Pop Allston, 89 Brighton Ave., Boston

“A giant ship with a city on it,” is how the Oakland artist has described her dreamy mural on the side of Pop Allston, the pop-up community space. The boat carries what look like barns or factories, a giant tree stump and abstracted people as it’s pulled along by (or moored to) a bird and star. And it hovers above diamond patterns.

The mural was painted as part of the Converse clothing company’s “Wall to Wall” and “Blank Canvas” projects, which have also financially supported murals by Kenji Nakayama off Washington Street near Somerville’s Union Square, Dana Woulfe in East Boston’s Newmarket area, Alex Lukas on Dorchester Avenue in South Boston, Kimou “Grotesk” Meyer in Boston’s Dudley Square, and Caleb Neelon around Boston and Worcester.

49. “Glove Cycle” by Mags Harries, 1984

Inside Porter Square MBTA stop, Cambridge

The 54 bronze gloves seemingly lost throughout the station — and especially cascading down the long escalator — feel like a monument to the pains of winter commuting. The Cambridge artist, who also created artworks embedded in the road around Boston’s Haymarket, writes on her website these sculptures “call to mind the gloves lost underneath winter snow and revealed again in spring appearing to have taken on a new life and history.” (Here's more on the gloves.)

48. Giant steaming tea kettle, c. 1870s

At 63-65 Court St., Boston City Hall Plaza

One of the first animated advertising signs in the United States, the charming giant tea kettle actually steams. The kettle was created to advertise the Oriental Tea Company in Boston’s old Scollay Square in the 1870s and became a sensation, the story goes, when the company held a contest to guess its capacity. Much drama ensued when it was publicly filled to determine the answer: “227 gallons, 2 quarts, 1 pint, 3 gills,” which was subsequently etched on the side.

The kettle survived urban renewal, so that today it continues to steam above a Starbucks. (It was temporarily removed in spring 2016 for repairs.)

47. Graffiti murals by various artists, since 2009

At Tobin School, 40 Smith St., Boston

Cambridge artist Caleb Neelon is the co-author of “The History of American Graffiti” and the painter of murals around the region (including recent ones at the ClubHouse at 471 Somerville Ave., Somerville, and at 510 Lincoln St., Boston) and the world. Since 2009, he and friends Katie Yamasaki, Risky and others have been quietly turning the Roxbury elementary school into a local oasis for graffiti and murals. The paintings are hidden all over the school’s campus. In 2015, one of the best (so far) appeared: a monumental, crowned figure painted by Boston artist Victor “Marka27” Quiñonez, with polkadots by Neelon.

46. “Connected by Sea” by Liz LaManche, 2014

At HarborArts, 256 Marginal St., East Boston

It’s been dubbed the “world’s largest tattoo.” As you walk out on this thousand-foot-long pier into Boston Harbor, under your feet the Somerville artist illuminates the cultures local maritime trade has connected with around the world by staining the concrete with a Chinese dragon, an Irish interlace pattern, Japanese waves, swirling graphic Maori designs from New Zealand, an English crown and rose, a Wampanoag turtle, an Indian peacock, and classic New England ship and mermaid tattoo designs.

45. “Scarlett O’Hara House”

At 3 Rollins Place off Revere Street, Beacon Hill, Boston

On Beacon Hill, behind an iron gate and gas streetlamp, at the dead end of a private cobblestone way lined with classic mid-19th century brick townhouses, is a surprise: a white, two-story, columned Greek revival house. Or so it appears. It’s been nicknamed the “Scarlett O’Hara House” for its loose resemblance to the character’s Tara plantation mansion in the 1939 film “Gone with the Wind.” In fact it isn't a house at all. The shallow porch is a faux façade, an elaborate sculpture.

“The charming house front is merely a wooden facing to a brick wall,” George F. Weston Jr. explained in his 1957 book, “Boston Ways: High, By and Folk.” “Its humane but prosaic purpose is to keep the wandering wayfarer from carelessly walking off the 40-foot cliff that lies behind it."

44. Graffiti

Around Sullivan Square MBTA stop, Boston

A prime place to spot graffiti in the wild around here is the MBTA’s Orange Line stop at Sullivan Square, and just inbound from there. It’s become a showcase for bubble-lettered throw-ups (an outline filled-in with a single color) as well as some large, complex pieces. Inbound from Sullivan Square toward North Station, a building on the east side of the tracks is covered with paintings, including a monumental topless wolf-woman by an artist who goes by the moniker Wolftits. On the west side of tracks there, old, derelict Boston and Maine Budd train cars parked near the Somerville yards have been covered inside and out with graffiti.

Some other places to check out graffiti locally are the railroad bridge near the Boston University Bridge over the Charles River; the Orange Line near Jackson Square in Boston; and commuter rail tracks, especially between North Station and Porter Square, but also along Route 90 between Allston and Route 95.

43. Chinatown Gate designed by Jung/Brannen Associates, 1982

Corner of Beach Street and Surface Road, Boston

Village gates and arches are a common feature of Chinese architecture that were embraced by Chinese-American communities across the United States over the past century. The iconic entrance to Boston’s Chinatown, with its foo (a transliteration of the word “fortune”) lions or dogs (there’s some debate on the proper translation) and twin green roofs, began with a gift of materials from Taiwan in 1976 in honor of America’s bicentennial, according to the Boston Art Commission.

Seeking to expand its international friendships as the rival Chinese communist government was beginning to open back up to the world, Taiwan supported construction of Chinatown gates across the U.S. during that decade, says Wing-kai To, a professor of Chinese-American history at Bridgewater State University and vice president of the Chinese Historical Society of New England. The gates were also a way to signal a neighborhood’s vitality and resolve as protection against the demolitions of urban renewal, he says.

If you’re looking through the gate to Boston’s Chinatown, the characters say, “All under heaven for the common good of the people,” one of the classical Chinese verses appropriated by the revolutionary Sun Yat-sen, sometimes called “the George Washington of China,” To explains. Sun Yat-sen helped overthrow the last Chinese dynasty and in the 1910s found the Chinese republic. The text on the reverse side of the gate, To says, promotes the Confucian moral values of “propriety, righteousness, integrity, uprightness.”

42. “Ars et Scientia” by El Mac, 2015

On Northeastern University’s Meserve Hall overlooking Centennial Common, 35-37 Leon St., Boston

At first glance, the LA artist’s spraycan mural appears to depict a goddess with a paintbrush in one hand and a lightning bolt in the other. But the artist’s inspirations were more personal — his father was studying engineering (the lightning) at Northeastern when he met his mother who was enrolled down the street at Massachusetts College of Art and Design (the brush). Thus the artist himself is the result of the union of “Ars et Scientia.” And the model for the goddess was the El Mac’s own wife, Kim.

The mural is part of the school’s “Public Art Initiative.” On the side of the Behrakis Health Sciences Center at 30 Leon St., across the grassy Centennial Common from El Mac’s artwork, is Boston artist Cedric Douglas’ striking 2016 mural "A World Of Innocent Discovery,” depicting dinosaurs emerging like genies from a child’s spray can.

The school’s public art also includes street art star Shepard Fairey’s wheatpaste mural in the school’s International Village lobby and street artist Jef Aérosol’s (Jean-François Perroy) spray-painted stencils of Jimi Hendrix, Tom Sawyer, Edgar Allan Poe and a giant leaping guy sprinkled outdoors around the campus.

41. “The Big Sail” by Alexander Calder, 1965

MIT campus, in McDermott Court, Memorial Drive, Cambridge

After Calder made his name with his signature hanging mobiles, the Connecticut sculptor began making “stabiles,” colossal painted steel abstract sculptures that stood on their own feet, in the 1950s. Calder’s art often charms with a feeling of jaunty, playful balance, but the three pointy “sails” backed by a rounded spinnaker shape give a prickly disposition to this 40-foot-tall, brawny black steel abstraction towering over McDermott Court.

(If you’re looking for more Calder, an 8-foot-tall model for “The Big Sail” stands in the lobby of MIT’s List Visual Arts Center and his 6-foot-tall “Onion” from 1965 sits near the sunken entrance to Pusey Library in Harvard Yard.)

“The Big Sail” is part of MIT’s notable collection of outdoor works by internationally celebrated fine artists, including Pablo Picasso, Louise Nevelson, Cai Guo-Qiang, Mark di Suvero, Dan Graham, Henry Moore, Tony Smith, Lawrence Weiner and Jaume Plensa.

Jump to: 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-1

40. Mural façade of the Museum of Modern Renaissance by Nicholas Shaplyko and Ekaterina Sorokina, since 2002

At 115 College Ave., Somerville

On the front of the Museum of Modern Renaissance is a mural depicting roosters (“In Slav traditions, it protects you from evil,” Nicholas Shaplyko explains), Pisces fish, lilies and a sun-face. In the middle of the painting is a large, carved mask-face, with flowers hanging down from a window box above as hair. It all hints at the mysteries inside.

The building, a former church and Masonic hall, has become the collaborative project of artists Nicholas Shaplyko and Ekaterina Sorokina. They moved to the U.S. from their native Russia in 1994, and have made the place their home, studio and artwork since 2002. “For us it means everything. It’s self-revelation,” Shaplyko says. “We just want to create something we can be proud of. We did it for ourselves and not to make a living, just to live.”

They’ve transformed the building into an icon of visionary art, filled inside and out with incredible paintings of radiating suns and stars, angels, flowers, mystical animals and all-seeing eyes.

“It is Modern Renaissance,” they write on their website, “that adopted the eclecticism of our life and creatively transformed it into its ideal counterpart, where mythological creatures peacefully converse with flowers, and fairy-tale landscapes harmonically incorporate complicated geometrical ornaments. It may be the key to many secrets of existence.”

They call it a museum because the word “means not just a warehouse for storage of artworks. It means a house where the muses are living,” Shaplyko explains. “In our place, everything is moving, everything is life.”

39. “Super Savers”/Supermen by Kim Giordano, c. 2008

Atop Expressway Toyota, 700 Morrissey Blvd., Boston

After seeing a TV commercial promoting the car dealership run by Robert and Richard Boch, who describe themselves as “Super Savers … price slashing superheroes with powers far beyond mortal auto dealers,” artist Kim Giordano approached the brothers with an idea. Giordano — who crafts signs, dinosaurs, skull mountains and other sculptures for amusement parks and casinos in his Norfolk shop —proposed he make portrait sculptures of the brothers as supermen. They agreed and over the next year or so, he painstakingly depicted the Bochs in somewhat-larger-than-life fiberglass over an aluminum frame.

“It was so important for him to make it look like us,” Robert Boch says. “Even though you can’t see our faces. I have a mustache and he put a mustache on it. I wear clogs and he put clogs on it.” Giordano adds, “If you take a close look at them, they’re dead ringers. Plus it’s a weathervane. It actually rotates.”

38. Sculpture garden at Luc Hoa Buddhist Center

7 Greenwood Park, Fields Corner, Boston

On a side street off Fields Corner, is a yellow gate with three arches. It serves as the entrance to a garden with potted topiary trees and statues arranged across the paving stones of the plaza. It’s a small oasis outside the Luc Hoa Buddhist temple.

The center began two decades ago when Buddhist members of the local Vietnamese-American community acquired the three-family home there that had been damaged by a fire, plus two open lots, and renovated them to become the temple. Luc Hoa, says Phap Hanh, a monk there, refers to the six ways the Buddha taught his disciples to live together in harmony.

The yellow gate has writings speaking about peace and joy, he adds. “The middle gate, you go through without attachments between wrong and right, without beautiful and ugly.”

The statues in the garden include guardian lions, a white statue of a standing Quan Am bodhisattva, a spiritual figure of love and kindness, and a reclining statue of Sakya Muni Buddha, exuding spirituality and tranquility, Hanh explains.

“We try to liberate ourselves from some of the things of this life,” Hanh says. “We know for sure this life is suffering. We try to cultivate our mind, liberate ourselves from this suffering.”

37. “Brewer Fountain” by Liénard, c. 1855

In Boston Common, along Tremont Street, near Park Street, Boston

Sensual bronze statues of the nearly nude Greek sea god Poseidon, his consort Amphitrite, the sea nymph Galatea and her lover Acis sit around the base of the 22-foot-tall Brewer Fountain on Boston Common. The title comes from Beacon Hill merchant Gardner Brewer, who, the story goes, acquired this fine example of 19th century French academic sculpture at the Paris Exposition of 1867 and brought it home to give to the city of Boston.

Locally it has frequently been said to be one of several castings of French sculptor Paul Liénard’s 1855 original. Which brings up a complication, as that Liénard seems to have been born in 1849 and specialized in jewelry. The fountain artist may have been the Frenchman Michel Liénard, who is said to have been born in 1810 and is credited with sculpting a number of fountains.

Regardless, “the design is one of much refinement,” as the Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin reported in the 1910s. And after a 2010 restoration that got the water flowing again, that’s still very much true.

36. Lions by Louis St. Gaudens, 1890

In Boston Public Library’s McKim Building, Copley Square

The Central Library offers a wealth of public art by John Singer Sargent, Daniel Chester French, Puvis de Chavannes, Bela Pratt, Edwin Austin Abbey and Frederick MacMonnies. (MacMonnies’ bronze statue “Bacchante and Infant Faun” in the courtyard fountain is a later cast of a version given to the library in 1894 by its architect Charles Follen McKim. The earlier version was withdrawn after Boston folks complained that the dancing nude woman was indecent.) But the majestic lions at the turn of the grand stairway inside the Dartmouth Street entrance to the BPL's McKim Building are the most prominent icons of the institution.

They’re one of the many local monuments to the state's contribution to the Civil War — in this case honoring the 2nd and the 20th Massachusetts Infantry regiments, and listing the locations of major battles in which these soldiers fought.

The lions were created by Louis St. Gaudens, the younger brother of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the celebrated sculptor of the “Shaw Memorial” on Boston Common. Louis, who came to shorten his name to St. Gaudens to distinguish himself, often worked as a studio assistant to his sibling. The lions, begun with plaster models then sensitively carved out of unpolished Siena marble, are among his finest independent works. Their stature was nodded to when the Central Library’s renovated Children’s Library opened in the adjoining Johnson Building in 2015 with the addition of light-up sculptures of lion cubs by 42 Design Fab of Springfield.

35. “John Harvard” by Daniel Chester French, 1884

In front of University Hall, Harvard Yard, Cambridge

John Harvard was a 17th century English minister, schooled at Cambridge University, who arrived at Charlestown around 1637, and died the following year from consumption (tuberculosis). Little else is known about him, but his name goes down in history because he willed half his estate and a library of 302 books to a Cambridge, Massachusetts, college founded the year before, becoming its first benefactor and namesake.

Considered Harvard University’s best known landmark, the seated metal figure’s toe is worn bright by visitors rubbing it for luck. (Be warned: A common student prank reportedly is to pee on the statue.) The fellow depicted, though, isn’t exactly Harvard, since no representations of him are known to exist. So the sculptor’s model was his friend Sherman Hoar, later a congressman.

34. “Tenango” mural by Mayor’s Mural Crew, 2014

At 2 Harris Ave. at Centre Street, Boston

Inspired by the building owner’s request for a Mexican motif — and a rooster — Heidi Schork, the founder and director of the Mayor’s Mural Crew, came up with a catchy graphic composition of flowers and birds around a rooster for this narrow, fenced-off alley sandwiched between two Jamaica Plain buildings. The imagery is inspired by traditional tenangos, which Schork explains are “an embroidered piece of cloth made by women in the state of Hidalgo in central Mexico. … Then the cloths are used as hangings.”

The Mural Crew, a summer work program for Boston teens, began in 1991 as an anti-graffiti project under former Mayor Ray Flynn. “Our first few summers were spent in Codman Square painting out gang graffiti,” Schork says. “Then it took on a life of its own.” After a quarter century, she says, “hundreds of Boston kids have been able to paint murals that have lasted a very long time. We have trained many kids and turned them on to public art. … The freedom of painting such a large wall is a lot of fun. But it’s a lot of hard work.”

33. “Mystic River Mural” by David Fichter and Somerville youth, begun 1996

Along Mystic Avenue (Route 38) at Shore Drive, next to Route 93, Somerville

The Cambridge artist has painted a number of murals around the region in his distinctive realist style — including in Cambridge at Trader Joe’s on Memorial Drive and on the Alewife MBTA station. But this mural that runs for hundreds of feet along Mystic Avenue, and was painted with teams of students and assistants over a number of summers, stands out with its epic size and its vivid depiction of the people and herons, hawks, foxes, frogs and fish that populate the local watershed. It showcases both the history and natural wonders here.

32. Greenway Carousel critters by Jeff Briggs, 2013

On Rose Kennedy Greenway, across from Faneuil Hall, Boston

This carousel offers the ride’s usual delights, while also being a one-of-a-kind celebration of Massachusetts wildlife. Take a spin upon 14 creatures from our region — harbor seal, skunk, barn owl, peregrine falcon, sea turtle (that appears to soar), lobster, whale, butterflies, the sacred cod, and a sea serpent.

Newburyport artist Jeff Briggs, a sculptor of highly realistic animals who has also long made carousel creatures, shaped the dazzling critters based on drawings by Boston school kids as well as his own research. Haverhill artist William Rogers painted the creatures. And the carousel machine was constructed by Ohio’s Carousel and Carvings.

31. “Paul Revere” by Cyrus Dallin, 1940

In Paul Revere Mall, North End, Boston

In this iconic bronze portrait, the Arlington artist (who also created “Appeal to the Great Spirit” in front of the Museum of Fine Arts and the statue of Anne Hutchinson outside the State House) depicts the Revolutionary War patriot (and artist of the famous engraving of the Boston Massacre) waving his arm as he rides his horse toward Lexington and Concord in 1775 to warn colonial militias that British troops were marching their way. Revere, of course, got captured before he reached Concord, but the legend of his “midnight ride” (from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1860 poem) rings through American history.

The statue stands behind the Old North Church, where the American revolutionaries actually hung lanterns to signal what British troops were up to. The statue continues to be embraced as a mascot for the city — getting dressed up in sports jerseys when local teams mount championship runs.

Jump to: 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-1

30. “Alchemist” by Jaume Plensa, 2010

In front of MIT’s Stratton Student Center, 84 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge

The Spanish artist’s public works often depict people — monumental stone heads that seem stretched digitally or seated figures with their knees drawn up to their chests as if in contemplation.

“Alchemist” is one of the latter. The other seated figures in this series generally are made from webs of stainless steel letters, painted white, but this 16-foot-high figure, commissioned by an anonymous donor to mark the 150th anniversary of MIT, uses numbers and mathematical symbols in homage to researchers and scientists. The statue speaks of MIT’s brand of ingenuity and the life of the mind.

“Our body is the home of the spirit. The place in which ideas live,” Plensa has said of one of the works in the series. “Taking the shape of a human body made out of essential vehicle of communication, the fundamental tools.” It’s particularly dramatic when lit up at night.

29. Whale mural by Ronnie Deziel, 1998

On Planet Self Storage, 33 Traveler St., Boston

Rhode Island artist Ronnie Deziel’s monumental mural of a trio of killer whales leaping out of the sea, with dolphins cavorting below, is an icon of Boston’s South End. Long visible from Route 93, the 125-foot-tall painting has become harder to see since a new building rose between it and the highway in 2014, but sharp eyes can still spot it as you drive by.

(Another whale mural visible along Route 18 in New Bedford was painted by a different artist, muralist Wyland, who has been painting “Whaling Walls” internationally since the 1980s to raise environmental awareness.)

28. Lion and Unicorn, c. 1901

Atop Old State House, 206 Washington St., Boston

The original Lion and Unicorn were sculpted and perched on the top brick corners of the Old State House around 1713 when it was the government offices of Britain’s Massachusetts Bay Colony. But after the Declaration of Independence was read form the balcony on July 18, 1776, the statues and other symbols of royal authority were torched in a bonfire.

So things stood until the 1880s, when the Bostonian Society formed and organized a museum of Boston's history in the building. One of the ways they marked the city’s revolutionary legacy was to commission wooden recreations of the king’s Lion and Unicorn and place them back atop the edifice, the oldest surviving public building in Boston. Weather rotted those away, requiring replacements around the turn of the 20th century, but those remain.

When the two royal beasts were removed for restoration in 2014, historians opened a time capsule that had been in the lion’s head since 1901. Inside, they found Boston newspapers; campaign buttons (including one for Teddy Roosevelt); a nail from Old South Church; photographs of several 19th century Boston mayors; and wood removed from "the Old Lion.” They refilled it with a 2013 Boston Marathon medal, a David Ortiz bobblehead and an iPhone 5, and sealed it up again for people of the future to discover.

27. “Arthur Fiedler Memorial” by Ralph Helmick, 1984

On Charles River Esplanade, near Hatch Shell, Boston

“This portrait addresses the mystery of personality and public perception,” Cambridge sculptor Ralph Helmick writes on his website. “Arthur Fiedler … was a man whose media image and private persona were at odds.”

The beloved conductor was a great popularizer of classical music, leading the Boston Pops Orchestra from 1930 until his death in 1979, and bringing it to worldwide fame via concerts, recordings and television broadcasts. He projected a genial, cosmopolitan public persona, though behind the scenes and at home he could be mercurial.

The seven-foot-tall sculpture gets its distinctive look — like rock strata, something blurred by speed, or a digital mirage — because it is made from 83 plates of aluminum stacked upon a granite base. It stands close to the Hatch Shell, where the free Esplanade concerts that Fiedler founded drew huge crowds. His Fourth of July concert for the nation’s Bicentennial in 1976 attracted some 400,000 people, said to be the largest audience ever for a classical concert.

26. Phillis Wheatley plaque by Boston Women’s Heritage Trail

Corner of Tyler and Beach streets, Chinatown

Phillis Wheatley is hailed as the first African-American, the first American slave and one of the very first American women to publish a book of poetry (“Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” 1773). That is why she is one of just three women honored (along with Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone) with a statue at the “Boston Women’s Memorial” on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue Mall. But a more riveting monument to Wheatley is this small, nondescript sign on a corner in Chinatown.

The marker is part of the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, begun in 1989 by Boston public school teachers, librarians and students “to restore women to their rightful place in the history of Boston.” The sign begins, “In 1761 at Griffin’s Wharf, near this site, John Wheatley purchased eight-year-old African American Phillis Wheatley (c.1753-1784) to serve as a domestic slave.”

The plaque can be seen as conceptual art (driven by ideas rather than looks) and psychogeography (a way of exploring the landscape by engaging with its psychological history). It helps us see this site anew, as a place transformed by time from harbor to a corner now blocks from the water. That transformation has helped hide that a great crime was committed here — a little girl was turned into Mr. Wheatley’s slave. The family gave her their last name and, for her first name, named her after the slave ship upon which she arrived.

Her achievement in becoming a groundbreaking author was so unbelievable to white people of her time, that her book begins with a note from then-Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and other eminences reassuring readers that she was actually the author: “The poems … were (as we verily believe) written by Phillis, a young negro girl, who was but a few years since, brought an uncultivated barbarian from Africa, and has ever since been, and now is, under the disadvantage of serving as a slave in a family in this town. She has been examined by some of the best judges, and is thought qualified to write them.”

25. “Charlestown Bells” by Paul Matisse, 2000

Near Paul Revere Park, Boston

The 30 metal tubes by the Groton artist (grandson of the famous French painter Henri Matisse, and also the creator of “The Kendall Band” chimes at the Kendall Square MBTA stop) ring out a delightful tune when struck by metal handles pushed by pedestrians crossing the Charles River Dam. After succumbing to weather and use, it was restored to musicality in 2013.

24. “Site of the Boston Massacre” marker by Bostonian Society, 1887

In front of Old State House, Devonshire Street at State Street

A ring of cobble stones with a star at the middle marks the site of the Boston Massacre, where on March 5, 1770, an argument between American colonists and British troops in tense pre-revolutionary Boston got out of hand and resulted in the soldiers shooting and killing five people. Paul Revere, who widely circulated his illustrated version of the clash (a knockoff of Henry Pelham’s earlier print), and other revolutionaries used the violence to rally people to their cause.

A century later, the event was also commemorated by Robert Kraus’ 1888 “Boston Massacre Monument” on the Tremont Street side of Boston Common, which has a stone column, the names of the people killed, and a bronze woman throwing off a chain and stomping upon the British crown.

That statue feels schmaltzy compared to the resonance of the humble stones embedded in the sidewalk, and the feeling of being on the very spot where this world-changing fight occurred. Well, except, it’s not quite the actual site. The actual site was out in the middle of the street (or around there; there’s some dispute). The marker ring used to be in the intersection, but has been moved a number of times over the years.

23. Tyrannosaurus Rex by Louis Paul Jonas Studios, 1966 to ’72

Outside Museum of Science, 1 Science Park, Boston

Museum of Science Director Bradford Washburn commissioned the Louis Paul Jonas Studios to sculpt a Tyrannosaurus rex after seeing the studio’s dinosaur sculptures at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. The dinosaur’s head arrived first two years later, and was driven around the city on a flatbed truck in an effort to raise money for construction of the museum building. The whole creature — standing upright, 20 feet tall and 40 feet long in fiberglass over a steel frame — went on display inside the museum in 1972.

But by the start of the new century, science suggested that the T-rex may actually have been lighter, more agile, and leaned forward more when it roamed. Which prompted the museum to commission a new dinosaur in 2000. When that creature went on display indoors around 2001, the old one was cut apart, reinforced, put back together and stood up along the museum’s driveway, outside the Mugar Omni Theater, in November 2002, where the beast has become a landmark.

22. “Archimedean Excogitation” by George Rhoads, 1987

At Boston Museum of Science lobby, 1 Science Park

George Rhoads, who was born in 1926, grew up outside of Chicago and is now based in Ithaca, New York, began his art career as a New York and Paris painter of expressionistic urban landscapes and trompe l’oeil scenes. But a lifetime interest in machines prompted him to make toys (his “Cliff Hanger” and was sold to the Milton Bradley Co.) and, beginning around the 1960s, kinetic art.

“The first ball machines were single-track, hand-powered devices, small enough to sit on the average coffee table,” according to his website. They evolved into big, elaborate contraptions with chain-drives that lift the balls up so they can roll down metal tracks, spiral around bowls, strike bells and chimes, and bounce down xylophones. They’re whimsical sort-of-rollercoasters that make visible gravity, basic physics and how machines work. In the 1970s, these kinetic pieces took off — with commissions from hospitals, airports, children’s museums and other institutions around the country and the world.

Around Boston, you can see his ball machines in the lobbies of Boston Children’s Hospital in Waltham, 9 Hope Ave., Waltham; Boston University’s College of Engineering, 44 Cummington St.; and at Logan Airport, one by the Terminal A baggage claim and the other at the Terminal E arrivals level outside customs.

But Rhoads' most spectacular kinetic work here is “Archimedean Excogitation” at the Museum of Science, which is 27 feet tall and includes balls of two sizes, on two levels, that, in addition to the usual delightful motion and music, spin windmill blades on top.

“Machines are interesting to everybody,” Rhoads has said. “But people usually don’t understand them because, as in a gasoline engine, the fun part goes on inside the cylinder. So I’ve restricted myself to mechanisms that you can see and understand quickly.”

21. “Roxbury Love” (Mandela) mural by Richard “Deme5” Gomez and Thomas “Kwest” Burns, 2014

On Warren Street at Clifford Street, Boston

The 100-foot-long mural is a statement of pride by and for Roxbury’s African-American community with its black and white portrait of Nelson Mandela, South Africa’s anti-segregation and anti-apartheid leader who died in 2013, flanked by the slogan “Roxbury love.”

The two artists who spraypainted the mural have said that, in part, it commemorates the visit Mandela made to Boston on June 23, 1990, just months after he was released after 27 years in prison. The international civil rights icon had come for a one-day stop to thank Boston for its support (Massachusetts was the first state to withdraw its pension funds from companies doing business in South Africa; the city of Boston soon followed) and as part of an eight-city U.S. tour to gather backing and raise money for a political campaign that would ultimately get him elected president of South Africa in 1994.

The mural also brings to mind the 1986 Boston ballot referendum question (ultimately defeated) that proposed that Roxbury secede from the city to become an independent, 12-square-mile, African-American majority city called Mandela.

Jump to: 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-1

20. “Taino Indians” mural by Rafael Rivera Garcia, 1984; restoration by Mayor's Mural Crew, 2003

Perkins Street off Centre Street, behind Whole Foods, Hyde Square, Boston

Garcia, a Puerto Rican artist and art professor, often adapted the abstract language of modernist painting to depict stories and myths from pre-Columbian Puerto Rico. In this mural, he painted bold, graphic representations of the Taino legends of the hurricane goddess Guabancex stirring up storms with help from the gods Guatauba and Coatrisque. They seem to fly across the expanse of the wall like superheroes.

Years of New England weather left it in “terrible shape,” explains Heidi Schork, the founder and director of the Mayor’s Mural Crew, a summer art program for teens, which restored the mural in 2003. “We took it right down to the primer and then tried to maintain the color based on what was left.”

19. “Nieli’ka” mural by Mayor’s Mural Crew, 2013

On Purple Cactus, 674 Centre St., Boston

“Nieli’ka are traditional Huichol art — that's an indigenous group from west central Mexico, from Jalisco, San Luis Potosi and Nayarit — made of yarn… There’s an intense use of color and it’s usually a kind of dream image,” explains Heidi Schork, the founder and director of the Mayor’s Mural Crew. “But it’s a nieli’ka in Jamaica Plain.” The mural features a brightly colored mask, monarch butterfly and blue jay (“a resident of Jamaica Plain, a sort of spirit animal”). Schork says, “The rest of the images are Jamaica Pond, a mallard and the willows around the pond; Jamaica Pond in the rain.”

18. “Tessie the Giraffe” by Lego Master Model Builders, 2014

At Legoland Discovery Center, 598 Assembly Row, Somerville

As Legoland Discovery Center was being developed, Master Model Builders at Legoland Windsor Resort in Britain were busy building a 19-foot-tall yellow giraffe from 22,000 Duplo bricks. The critter — the official mascot of Legoland Discovery Centers; they generally each have one somewhere on the property — was sent here by cargo ship, and its inner steel frame was anchored four feet into the ground to withstand local weather as well as climbing kids. Now it’s becoming an advertising landmark — big, yellow and fun.

17. Jamaica Pond Bench by Matt Hincman, 2006

At Jamaica Pond, near Pond Street, Boston

The Boston artist snuck his art park bench into Jamaica Pond in May 2006 without approval. It looked like all the others, including being anchored to an open concrete pad, except it had two backs bending up to meet each other. The surreal change prompted double-takes.

It stood there about a week before officials carted off the curious thing. But soon officialdom embraced it, at first for short stays, then longer and longer. Hincman has since perpetrated other guerrilla art — like a medallion surreptitiously secured atop an old, broken lamppost at the corner of Eliot and Centre streets in Boston in 2014 that depicts a hoodie to memorialize the murdered Trayvon Martin. Hincman’s bench, still at Jamaica Pond, remains a delight, a rascally joke that you can crawl into.

16. “Madonna Queen of the Universe Shrine” by Arrigo Minerbi, 1954

At 150 Orient Ave., East Boston

The origins of the monumental, 35-foot-tall statue of Mary standing atop the earth at this Roman Catholic shrine trace back to World War II. The Jewish sculptor Arrigo Minerbi had a successful art career in his native Italy until, to escape the Holocaust, he went into hiding with the Roman Catholic priests of the Don Orione order of Rome. After the war, the order wanted to erect a statue in thanks for the peaceful liberation of Rome from German forces. And, Minerbi, in gratitude for the priests’ protection during the conflict, designed a monumental statue of Mary, the mother of Jesus, that was erected at the order’s center there in 1953. When the order opened a home for the elderly in East Boston’s Orient Heights, Minerbi oversaw the casting of this 35-foot-tall bronze and copper replica, which debuted in 1954.

The shrine plaza, which now sits atop a church, offers panoramic views of Logan Airport and the rest of Boston. It’s a spectacular place to see sunsets.

15. “Bunker Hill Monument” by Solomon Willard, 1842

At Monument Square, Charlestown

On June 17, 1775, the first major battle of the American Revolution was fought around Bunker Hill and — here — Breed’s Hill. It was sparked by a misbegotten decision by Massachusetts revolutionaries to put cannons too threateningly close to British outposts on the peninsula of Boston. British forces responded and the revolutionaries lost. But they lost in good enough fashion by inflicting enough casualties that instead, we remember the cry, "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes,” and the revolutionaries could claim they held their own.

In 1794, an 18-foot-tall wooden pillar with a gilt urn was erected on the site. Plans began in 1823 to put up something more permanent, but it wasn’t until 1842 that the 221-tall granite obelisk — predating the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., and symbolic of the nation’s neoclassical, republican ideals — was completed.

14. “Gift of the Wind” by Susumu Shingu, 1985

At Porter Square, Cambridge

Though abstract and industrial-looking, Shingu’s wind-powered artworks are about seeking harmony with nature. “Through sculptures and all my activities, I always want to express the same thing,” Shingu said in a 2014 profile by the Japan Times. “And that is how lucky are we to be born on this planet — a planet that is so beautiful and so delicately balanced.” In “Gift of the Wind,” three red steel sculptures cup the wind, rock on their arms, and spin around a 46-foot-tall central post high above the MBTA Red Line station. Part of its pleasure is how something so big and seemingly heavy is so carefully balanced that it spins so gracefully in the breeze.

(Shingu also created the 2000 kinetic sculpture “Wind Traveler” in Eastport Park in Boston’s Seaport/World Trade Center area.)

13. Giant Milk Bottle by Arthur Gagner, 1934

Outside the Boston Children’s Museum, 308 Congress St.

USA Today called it one of the “most quirky landmarks across the USA” in 2014. This four-story-tall wood and plaster milk bottle was built by Arthur Gagner in 1934 as an ice cream stand on Route 44 in Taunton. After the business closed, one proposal called for placing it on Boston City Hall Plaza. Instead, it was refurbished in red and white in 1977 by the Hood Milk Company and placed here -- operating again as a snack stand, delighting children and becoming a local icon.

12. Rainbow gas tank (untitled, but often called the “Rainbow Swash”) by Corita Kent, 1971

On Victory Road at Boston Harbor, Dorchester, Boston

In 1971, Boston Gas commissioned a famous former nun to create murals for its two giant, liquefied natural gas storage tanks along the Southeast Expressway (Route 93) in Dorchester. For one, Corita Kent dreamed up with a rainbow: “A sign of hope that urges you to go on."

Kent had been a nun, artist and teacher with Los Angeles’ Immaculate Heart of Mary order. Her screenprints aligned pop art graphics, Roman Catholic social justice work and President Lyndon Johnson’s 1960s anti-poverty programs and civil rights efforts. The spirit of her work was also inspired by the feeling of Catholic renewal then emerging from Pope Paul VI’s Vatican II council. Kent became a symbol of this liberating transformation and one of the most prominent nuns in the U.S., featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine in December 1967 as the face of “The Nun: Going Modern.” But the cardinal overseeing the LA archdiocese loathed the pope’s changes and chastised the Immaculate Heart order for embracing them. He sent a committee to question every nun in the order about her faith and dedication to the church.

Under this pressure, nuns began to leave the order, including Kent who departed in 1968. She was on sabbatical in Boston and settled here, a sort of refugee separated from her friends, from the Catholic college teaching she’d done for decades, from the school printshop where she’d made her art, from the church and faith that had been central to her whole life. In her first years here, she produced prints that were among her most strident and activist — memorializing the murdered Martin Luther King, celebrating Cesar Chavez, and protesting the Vietnam War.

Somewhere in there, devastated by her personal losses and the larger problems of 1960s America, Kent burned out. Her rainbow gas tank design (which was painted by professional sign painters) comes from this moment of transition. As she regrouped, now and again she continued to address war or the nuclear arms race, but her art grew more light and sunny, more laid back and peaceful, based on loose watercolor brushwork. The rainbow gas tank is one of these paintings blown up 150 feet tall.

A controversy arose when some claimed to see the profile of Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese communist president and Vietnam War icon, in the rainbow gas tank’s blue brushstroke. People thought it seemed like the kind of thing a famous activist artist and a critic of the war might do. “So ludicrous, that’s not me, that’s not how I work,” Kent told a friend. It would be unlike her — she was a pretty straight-ahead kind of artist, not usually the sort to try to sneak in secret messages.

After the controversy, a butterfly design she drew up for the second gas tank was never painted. But the rainbow stripes have remained, becoming a beloved Boston landmark. When the tank was demolished in the 1990s, Kent’s rainbow design was repainted on a neighboring one. “To me, a rainbow represents hope, uplifting, spring,” Kent told The Boston Globe in 1971. “It’s a joyous expression, joining heaven and earth together.”

11. Reflecting Pool designed by architect Araldo Cossutta of I.M. Pei & Partners, 1972

At Christian Science Plaza, Huntington Avenue, Boston

Named a historic landmark by the city in 2011, the vast concrete space between the century-old cathedral and modernist concrete buildings at the Christian Science Plaza feels both meditative and awesome. It’s partly how the buildings seem to embrace the plaza, but it’s also how the space is filled by the monumental reflecting pool, 690 feet long, 100 feet wide, running parallel to Huntington Avenue. To give this much valuable open real estate in downtown Boston over to a pool — a pool just for looking — can feel astounding. That extravagance is part of its power. But it’s also something about the mix of nature and human-made, about the way light shimmers across it, about the hush of water cascading over the sides of polished Minnesota red granite. It’s a marvel.

Jump to: 50-41 | 40-31 | 30-21 | 20-11 | 10-1

10. Citgo sign, 1965

At 660 Beacon St., Kenmore Square, Boston

The red and orange triangle in a white square advertising the Venezuelan oil company has long been a signature sight along Boston’s skyline — especially as its flashing lights illuminate the city at night. The company says it has had a billboard there since 1940, but the triangle — with its echo of Malden-native Frank Stella’s 1960s geometric abstractions — dates to a rebranding in 1965.

The sign began a transformation from simple advertisement to something more when community opposition and a stop order from the Boston Landmarks Commission halted company plans to demolish the neon sign in the early 1980s. The commission ultimately rejected a proposal to grant the sign official landmark status in 1983, but the company restored the sign and has kept it lit. In 2010, the 60-foot-by-60-foot sign’s lights were replaced with LEDs.

Its future is again is question, as Boston University is selling the building atop which it sits at 660 Beacon St. The nonprofit Boston Preservation Alliance is pushing for the sign to be granted landmark status. The landmarks commission voted in July to begin considering the designation.

9. “Freedom Trail,” 1951

From Boston Common to Bunker Hill

The Freedom Trail’s red line — in places painted, in places red brick — that snakes through the Revolutionary War historic sites in the heart of Boston is one of those successes so big and so obvious in retrospect that it’s easy to take for granted.

It began in 1951 because Bill Schofield wanted to connect with the revolutionary history here, but even as an editor and columnist for the old Herald-Traveler newspaper, he found himself getting turned around and disoriented when attempting to visit all the sites. Imagine if he didn’t know the town?

Through conversations with Bob Winn, sexton of the North End's Old North Church, they drafted a walking route. Schofield publicly floated the idea in his March 8 column. "All I'm suggesting is that we mark out a 'Puritan Path' or 'Liberty Loop' or 'Freedom's Way' or whatever you want to call it, so [visitors and locals will] know where to start and what course to follow,” he wrote. “You could do the trick on a budget of just a few dollars and a bucket of paint."

After more columns pushing the idea, his March 31 essay announced: "A telephone call from Mayor John B. Hynes brings the news that the city intends to go along with the Freedom Way plan proposed here.”

That June, workers put up signs along a mile and a fifth route from Boston Common to the North End. It quickly became a hit. The trail has evolved over the years — the red line added in 1958 at the suggestion of businessman and philanthropist Dick Berenson, the route extended to Charlestown in 1972 to reach all 16 sites featured on it today. And the Black Heritage Trail and the Women’s Heritage Trail have been created, in part, to note what the original trail overlooked.

The Freedom Trail can be seen as a sort of artwork because it’s a giant line drawn through the city — but also because it invites acts of psychogeography, exploring the landscape by engaging with its psychological history. The trail is a set of directions on how to walk a certain way, on how to perform a sort of ritual by visiting the actual sites and stepping back into history.

8. “Swan Boats” by Robert Paget, 1877

At Boston Public Garden pond

In 1877, Robert Paget, who had operated boat tours for a few years on the Public Garden’s pond, came up with a new foot-powered paddle-wheel catamaran inspired by bicycles. As a pretty way to conceal the vessel’s laboring pilot, he thought of an opera — Richard Wagner’s mid 19th century "Lohengrin," with its tale of a knight crossing a river in a boat pulled by a swan to defend a princess. So the back of the boats got their first giant swans, which have become one of the icons of Boston. The boats have grown bigger over the years to accommodate more passengers, but the swans’ curving forms continue to embody their original genteel Victorian elegance.

7. “Betances Mural” by Lilli Ann Killen Rosenberg, 1979

At Villa Victoria, Aguadilla Street, off Tremont Street, Boston

A pair of brilliant suns, that also can be read as islands, radiate from either end of this 45-foot-long ceramic mosaic. It celebrates the Puerto Rican heritage of many residents of Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción’s Villa Victoria housing in Boston’s South End, which arose out of late 1960s activism to prevent the displacement of the neighborhood’s residents.

Rosenberg — who also oversaw the creation of ceramic mosaics at Boston Common’s Tadpole Playground, the MBTA’s Park Street station, Miller River Apartments in Cambridge and Lynn Heritage State Park — organized more than 300 children and Villa Victoria residents to sculpt clay tiles.

Fish, people and musical instruments float across the design. In the center is Rosenberg’s sculpted-cement portrait of 19th century Puerto Rican patriot Ramón E. Betances, who lead an (unsuccessful) independence uprising against the Spanish colonial government, and his words: “We must know how to fight for our honor and our freedom.”

6. “Orange Dinosaur,” c. 1960

At Route 1 Miniature Golf, 1575 Broadway, Saugus

The 12-foot-tall, dayglo orange T-rex was installed around 1960 to attract business to the entertainment complex. It has become a beloved regional landmark — fun, funny, monumental, orange. But the iconic sculpture’s status is threatened after Lynnfield developer Michael Touchette proposed building a complex of apartments, restaurants, hotels and retail space on the three-acre property, which has been home to mini golf since 1958, and adjoining land.

Last fall, owners Diana and Richard Fay announced that the facility was closing for good at the end of the warm-weather season, but in spring 2016, after redevelopment was delayed, they opened again for what Diana Fay called “one more season of memories.” Touchette has said he might possibly keep the iconic dinosaur. The orange monster has lived through tough scrapes before, including being pushed over and having its fiberglass ankles broken in 2007, so perhaps it will survive another brush with extinction.

5. Memorial buttons by Louis D. Brown Peace Institute, since 1994

At various locations around Boston

“It started after Louis was killed,” says Tina Chéry, president of Boston’s Louis D. Brown Peace Institute.

A stray bullet from a shootout between men on a December afternoon in 1993 hit her 15-year-old son. “A friend of mine for Louis’ funeral created some buttons that said ‘Save the children,’ ” Chéry says. “After he was laid to rest, I didn’t know what I could do.”

She began making buttons to memorialize other homicide victims that she read about in the newspaper. She’d send them to the reporters who wrote the articles and ask them to pass the buttons along to the families.

As she co-founded the institute, which provides support to people devastated by homicides, mainly gun and gang violence, the institution began giving memorial buttons to families as one of its services. You see a young face in the center, a name, dates of birth and death, and a statement: “Gone but not forgotten,” “Loving words & wit not violence,” “Peace in my name,” “You’ll be in our hearts forever.”

At the institute’s annual Mother’s Day Walk for Peace in Boston you can see the “Traveling Memorial Button Project,” a banner covered with hundreds of them, marking the vast toll of heartbreak. “It’s a reminder that the names are real, the faces are real, and the pain is real,” Chéry says.

But the buttons are all around us, every day, worn one by one — or a few worn at a time — by a person, often a teenager, riding the T or walking through a neighborhood.

"My brother," Shawnasa Settles of Boston said of the button showing a smiling young man in a hoodie that she wore pinned to her backpack while on the Green Line one recent summer afternoon. "He got shot in the back of my house." D’Andre "Cooper" King-Settles was just 17 when he died at the playground next to his Mission Hill apartment building in December 2015. The bottom of Shawnasa Settles' button read: "Hope for Justice & Healing."

At times over the years, some have claimed that the buttons spark continued feuds and retaliations. “The buttons are there because the violence is happening and as a city we have not created the healing spaces,” Chéry says. “This is their public way of wanting you to know someone I love was murdered and to say, ‘I need help, I need healing.’ ”

4. Graffiti Wall by various artists, since 2007

At Modica Way next to 567 Massachusetts Ave., Central Square, Cambridge

In fall 2007, Central Kitchen owner Gary Strack and financial adviser-turned-artist Geoff Hargadon transformed the exterior wall of the restaurant into a place where graffiti is welcomed rather than buffed. One of the rare places in the region where graffiti can be done legally (another is along the MBTA tracks in Beverly, and there is talk of creating a new one at Boston’s Mozart Park), it’s become a showcase for major pieces, painted over each other, for a spectacular, ever-changing exhibition. Revered street artists (Shepard Fairey, Swoon) have worked there when passing through town. It’s also a place memorials pop up — lately to David Bowie, Prince and Muhammad Ali.

3. “Make Way for Ducklings” by Nancy Schön, 1987

At Boston Public Garden, near Beacon and Charles streets

The children’s book author and illustrator Robert McCloskey won his first Caledecott Medal for his 1941 book “Make Way for Ducklings” about a family of ducks that make their way from a nest at the Charles River to a new home on the island in the Boston Public Garden’s pond — with police directing traffic along the way. The reassuring tale has become a childhood classic.

Urban planner Suzanne DeMonchaux thought it would make a great public sculpture for Boston — modeling how cities can be more friendly to children. With support from city and park leaders, she raised money and enlisted Newton artist Schön to sculpt the ducks. But a sticking point was McCloskey himself, who resisted commercialization of his works and had not responded to DeMonchaux’s inquiries. She finally got a neighbor to track him down and (the late author said in interviews) his wife finally talked him into it.

The bronze Mrs. Mallard, who stands about 3 feet tall, followed by her eight ducklings have become a hit themselves. Schön — who also created “The Tortoise and the Hare” on Boston’s Copley Plaza to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Boston Marathon, a dragon at Dorchester’s Nonquit Street Green, and a bronze Winnie the Pooh and friends at Newton Free Library — designs her sculptures to invite touch. People have wholeheartedly embraced this, with children riding the ducks daily, and adults dressing them up for holidays and in sports jerseys when Boston teams make playoff runs.

And each Mother’s Day, children dress up themselves for the annual “Duckling Day” promenade from Boston Common to the sculptures in the Public Garden, recreating the ducks’ famous journey.

2. “New England Holocaust Memorial” by Stanley Saitowitz, 1995

On Congress Street between Hanover and North streets, Boston

Stephan Ross was just 9 years old when he was imprisoned by the Nazis. Between 1940 and 1945, he survived 10 different concentration camps, while his parents, a brother and five sisters were murdered. “His back was broken by a guard who caught him stealing a raw potato,” the monument’s website explains. At 14, he was finally freed from Dachau by American troops. He came to the U.S. in 1948 via the U.S. Committee for Orphaned Children, went to college, and worked for the city of Boston for decades, “providing guidance and clinical services to inner-city youth and families.”

Late in life, Ross, along with other camp survivors in Boston, proposed a monument to the Holocaust here. Designed by architect Stanley Saitowitz, a row of six 54-foot-tall glass towers hauntingly evoke the smokestacks of the six main Nazi concentration camps in Poland. Their glass is etched with millions of numbers like those tattooed on death camp prisoners. The monument invites you to walk along a path among and into the towers. Steam emanates from pits under each — like smoke from the camp ovens, like spirits.

“They are towers,” Saitowitz has written, “of hope and aspiration.”

1. “Shaw Memorial” by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1897

On Boston Common, along Beacon Street at Park Street, across from the State House

“The Shaw Memorial has been acclaimed as the greatest American sculpture of the 19th century,” according to The National Gallery of Art. “It is our most intensely felt abolitionist work of art,” The Washington Post has written.

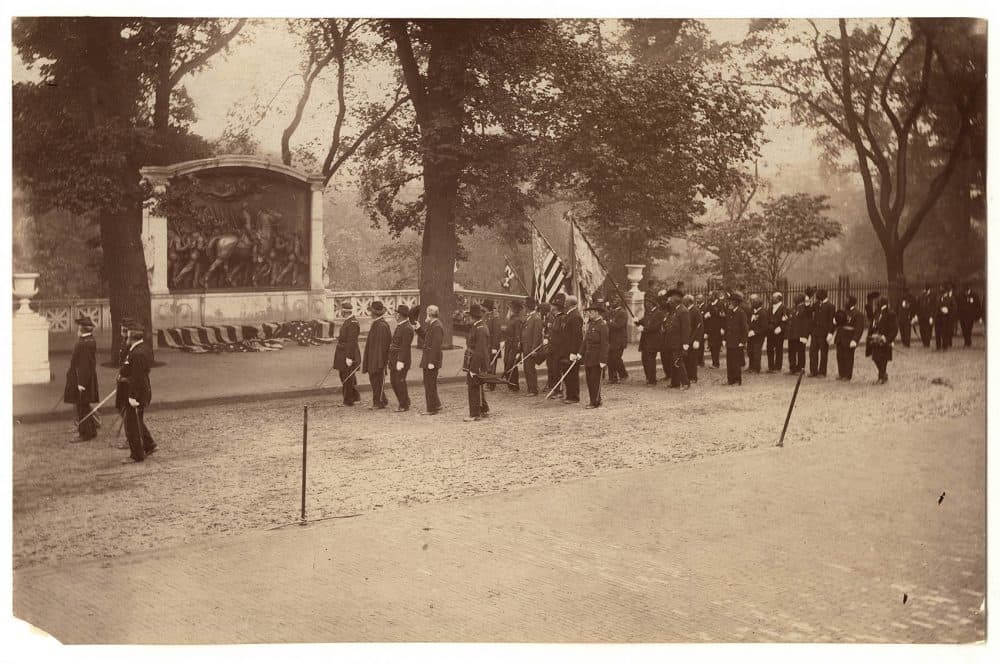

The monument was unveiled on the overcast morning of May 31, 1897, Decoration Day (what we now call Memorial Day), as 65 aging veterans of the legendary Massachusetts 54th Regiment marched past the corner of Boston Common at the State House.

The bronze bas relief was a testament to their service in the Civil War, the African-American unit that pioneered the integration of U.S. fighting forces during that war against slavery. The statues depicted the men three decades before, in uniform, with rifles on their shoulders, leaving Boston to march off to battle. The center of the bronze depicted their leader Robert Gould Shaw, the white aristocratic son of ardent abolitionists, steadfast atop a horse. Above Shaw, a bronze, mourning angel hovered.

That morning, a band had played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Cannons on the Common and on three warships in Boston Harbor had blasted salutes. The crowd cheered as retired Sgt. William Carney passed carrying the American flag. During the regiment’s legendary July 1863 attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina, Carney had picked up the American flag after another soldier dropped it. Though shot, he briefly planted the flag on the fort’s parapet before the regiment retreated under withering fire that killed or wounded 280 of the men, nearly half of those who began the assault. Among the dead was Shaw, who led the charge. For his daring, Carney became the first African-American awarded the Medal of Honor.

The aging veterans laid a wreath of lilies of the valley before the new monument. “Many of them were bent and crippled, many with white heads,” wrote artist Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who sculpted the monument. “They seemed as if returning from the war, the troops of bronze marching in the opposite direction, the direction in which they had left for the front, and the young men there represented now showing these veterans the vigor and hope of youth. It was a consecration."

The monument had been a long time coming. As early as July 1863, Union soldiers proposed a monument to Shaw. Initial plans called for it to be placed near Fort Wagner, but the ground was considered unstable and locals there opposed the monument.

So it wasn’t built. Instead money for its construction went to the first free school for African-American children in Charleston, the birthplace of the Confederacy, which was named for Shaw. Soon African-American businessman Joshua Benton Smith proposed building a memorial in Boston. But it wasn’t until 1883 that Saint-Gaudens was given the sculpture commission.

The sculptor initially envisioned a statue just of Shaw upon a horse, but Shaw’s family objected, so he expanded his design to honor the black soldiers as well. To achieve his deeply sensitive realism, Saint-Gaudens hired African-American men to pose, and modeled some 40 different plaster heads as studies. But the sculptor moved slowly as well, much to the consternation of the monument committee: “People are grumbling for it, the city howling for it, and most of the committee have become toothless waiting for it!" Saint-Gaudens said it took time to do “everything that lies in his power to execute a result that will not be a disgrace.”

Upon its unveiling, the “Shaw Memorial” was hailed as a triumph. Novelist Henry James called it “real perfection.” The scale of the monument and its prominent placement — on Boston Common, facing the Massachusetts State House — signal the state’s pride in the regiment, in the state’s leading role in the abolitionist movement, in the state’s continued commitment to equality.

“The full measure of the fruit of Fort Wagner and all that this monument stands for will not be realized until every man covered with a black skin, shall, by patience and natural effort, grow to that height in industry, property, intelligence and moral responsibility, where no man in all our land will be tempted to degrade himself by withholding from his black brother any opportunity which he himself would possess,” African-American leader and educator Booker T. Washington said at one of the dedication events. “Until that time comes this monument will stand for effort, not victory complete.”