Advertisement

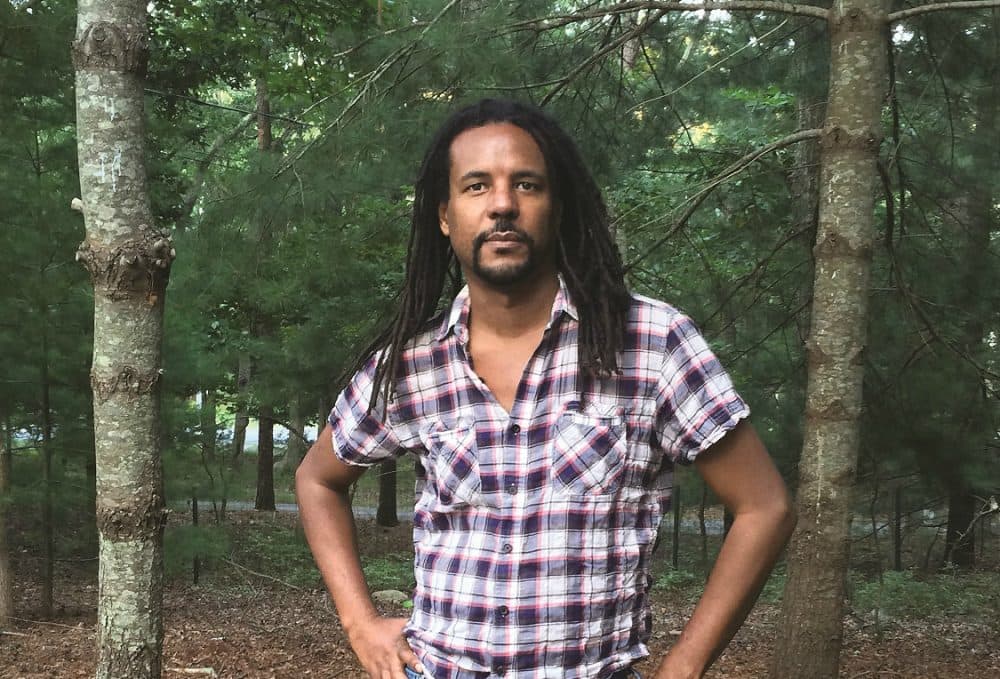

Colson Whitehead Creates A Literal And Fantastical 'Underground Railroad'

Colson Whitehead has ridden a few big waves over the years as a bestselling author and a Pulitzer Prize finalist. But he’s experienced no wave quite like the one he’s riding now with “The Underground Railroad,” a lacerating story of slavery set in the Deep South.

Not that acclaim or success was unanticipated by the writer. “Enthusiasm for the book had been building ever since I handed it into the publishing house and then booksellers were getting it,” Whitehead says, on the phone from his Nashville hotel room. “I knew it was going to sell well initially and that people who weren’t necessarily attracted to the premises of my earlier books would pick it up.” (His previous novel, “Zone One,” dealt with zombies in a post-apocalyptic New York.)

But then… Oprah relaunched her Book Club with “The Underground Railroad” and raved that it “kept me up at night, had my heart in my throat, almost afraid to turn the next page.”

The New York Times top book reviewer Michiko Kakutani called “The Underground Railroad” “potent, almost hallucinatory” and put it in the same company as Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” and Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” adding there were “brush strokes borrowed from Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka and Jonathan Swift.”

And in August, President Obama made it one of his summer vacation reading list choices. It’s currently at No. 4 on the Times’ hardcover fiction list.

So, is Whitehead — a Harvard grad who speaks at the Boston Book Festival Oct. 15 — feeling it, riding the high?

“Yes, as much as I can manage,” he says, with a slight laugh. “It’s my eighth book and it doesn’t always go this way. The short answer is: I’m very happy. I’m in a very good mood.”

Whitehead’s protagonist in “The Underground Railroad,” his sixth novel, is the teenage girl Cora, who with her mother Mabel (and many others), are slaves on a Georgia plantation owned by two brothers. The humiliations and punishments are relentless. Whippings are commonplace, lynching and being burned alive for more extreme violations. Whitehead’s fantastical premise, the Underground Railroad — the means of a slave’s escape to the free states — is real, not a metaphor.

Advertisement

Jim Sullivan: When I saw you on Seth Meyers’ show recently, I was surprised to hear you say when you were first taught about the Underground Railroad, you — like me — thought it was a real thing.

Colson Whitehead: Sure. For about one minute that’s what I believed. Then my teacher continued to explain.

What made you turn that Underground Railroad metaphor into a reality for your book?

It’s such a great notion and growing up in New York, why not? A literal subway over all of America.

That’s a major fantastical component in hard real-life story. One thing I really like, the way you did this, I accepted the idea of this railroad immediately.

It was really just that happy accident of thinking: What if? And then pretty quickly I added the second element of having each state that our protagonist goes through — South Carolina, North Carolina — being a different state of America, being a possibility of what might have been. I had the idea 16 years ago and back then I was in a very ‘what if?’ mode. What if an elevator inspector had to solve a criminal case? [The plot from 1999’s “The Intuitionist.”] So this is a holdover from my ‘what if?’ period.

During the Seth Meyers bit, you told him you couldn’t have written the book back then because you were “a douchey Gen Xer.”

Yeah, I was 30 and the idea seemed great, but I knew I wasn’t emotionally mature enough to tackle something like slavery. I had a vague notion what the book would be, but I knew that it would require a deep dive into a kind of research that I was reluctant to do at that time. I’d just finished a very complicated book — that was “John Henry Days” — and I didn’t think I had another complicated book in me. It had a sprawling structure that jumps around in time and I felt I wasn’t up to the task.

Was there a turning point where you said, “Yes, I can write this?”

I would finish a book and I’d pull up my notes every couple of years and realize I still wasn’t ready. My last book was a humor book [2014’s “The Noble Hustle: Poker, Beef Jerky, and Death”] about the World Series of Poker. The main character takes off from my personality and is kind of like a wise-cracking depressive. I had an idea for a book that was similar and it just seemed that I’d already sort of done it. I didn’t want to do it again. I’m always trying to switch voices and genres.

You often use humor in your writing. This book, obviously, not so much. Was it hard to keep that in check or was the topic so heavy you weren’t even tempted?

The story was so serious, once I signed on and committed to it, I knew that the usual satirical or ironic distancing wouldn’t serve the story. Here and there, the narrator exhibits a bit of sardonic wit because there are just so many horrible ironies with slavery and how we treat each other, it sneaks in here and there. But definitely in terms of the jokes-per-page-count, compared to my last book, it’s not going to match up.

What gives the book its horrific tone is the matter-of-fact tone of the prose, almost reportorial, which has the effect of making the evil and carnage all that more revolting. The narrator speaks dispassionately about the value of the slaves as property. The narrator describes passing a row of trees with executed slaves hanging from the limbs, as if it’s just part of the landscape. How did you decide to take that tone?

I think a lot of the drama is in the silences. By not belaboring some of the brutality of slavery and letting the reader’s mind work on it, I think it was more powerful. I think the tone I got from a lot of slave narratives I read. Someone would write something like “I saw my mother sold off. I never saw her again. Next was my first day in the fields.” And those sentences contain so many years and so much pain. I was reading these oral narratives taken down in the ‘30s by people who had been kids or teenagers at the time of slavery. Time had moved them away from the immediacy of what they’re describing. I thought that a matter-of-fact, sort of numb cataloging of what happened to them would be effective for the book.

You often use the same style for those on the other side of the divide, the so-called “regulators” and “night riders” who hunted down runaway slaves and returned them to face certain death on the plantations. They’re just doing their job, in a way.

It’s just work. A slave runs away, you discipline them. You just do it. It’s money. And that’s their business. I think today’s corrupt policemen find an echo in the slaver patrollers of 150 years ago. I’m sure when they talk among themselves and describe a shakedown or planting a gun, it is routine. If you’re in that world and committing atrocities, you don’t step back and realize how absurd and horrible what you’re doing is.

Over the past few years, we’ve seen “12 Years a Slave,” “Django Unchained,” the “Roots” mini-series remake, your book and upcoming, Oct. 7, the movie about Nat Turner and the slave rebellion, “The Birth of a Nation.” Why now?

I can’t really say. We’re not all in the same genre and not thinking about things in the same way. I think while Hollywood is not very diverse, we do break down doors bit by bit. I think there is a critical mass of people in their 20s and 30s and 40s who are now getting to make films, and slavery is a huge topic. It’s where we come from as Americans, as African-Americans, and there are so many different stories that have been told. To think it took all these years to have a really good Nat Turner biography! Where’s the John Brown and Harriet Tubman movies? A lot of the heroes of slavery — the railroad [people], the abolitionists — haven’t got their due and it’s great material.

Will “The Underground Railroad” be a movie?

Talking to some people and there’s someone interested in trying to get some money together to make a short mini-series out of it. But we haven’t seen any money, so it’s sort of abstract.

Kind of a step-back question: What do you think allowed for the mentality of slavery — the acceptance and endorsement of it — to go on so long? Slavery was abolished in England in 1833. Did the southern whites see the writing on the wall and fear the abolition?

I think it was a huge economic engine and [the thought that] you’re going to start paying these people who are making all this money for you doesn’t make sense. You’ve been brutalizing them. How are you going to set them free? In some states, the white population and black population were equal and they were justifiably afraid of retribution. Slave revolts were always put down quickly, but obviously there was lots of fear. There’s darkness in the human soul and it was expressed at that time through slavery and then through Jim Crow laws and lynching. We experience it now when we demonize Mexicans coming over the border, or Muslims. It’s just part of human nature.

I like this line in the book: “Fear drove these [white] people, even more than cotton money. The shadow of the black hand that will return what has given.”

The violence we’re talking about there, people want to get away from the South. Whether you were upholding the system or trying to break it down or fleeing it, you had to confront the fact that there were millions of slaves and they’ve been treated quite poorly.

In the book, you delve further back into American history and note — again, rather matter-of-factly — that what Europeans did when they came here was to steal land. That was great crime No. 1 and slavery great crime No. 2. This is who we are. Do you think that legacy taints any moral authority the U.S. tries to wield these days?

I don’t think we have any moral authority. You’re asking the wrong person.

Well, we try to wield it…

Certainly we whitewash our imperialist past — even the last 100 years, toppling governments and propping up regimes and stealing oil. I think all those world-hungry, world-grabbing impulses that led to subjugating Africans and stealing Native American land and pushing them further and further west and killing them off — they are certainly a real engine in our foreign policy still.

Does this history and ongoing situation ever make you say: “Hey, I’d rather live elsewhere?”

Oh no, I’m a New Yorker. I’m raising kids and so much of American culture sustains me and gives me things to think about and work on. If Trump gets elected, maybe I’d reconsider, but for now we’re here.

I know you’re mixing fiction with history, but I wanted to ask you about that row of hanged slaves — the “strange fruit” as it were — that, as readers, we pass by.

The Freedom Trail. It is not a true thing.

You also depict these weekly open-air “parties” in a certain town. It’s all fun and games for the white folks, with skits done in blackface … and then the climax comes when a slave is brought out to be lynched.

In terms of the weekly lynching, they weren’t weekly, but lynchings were public spectacles. You can buy postcards from the era, [people] crowding around someone who was strung up or burnt up. When I did put some brutal facts in there I would go “Am I going too over the top?” And I would go back to my research and go, “No, actually. This is how human beings were treated.”

Your protagonist Cora is forced to hole up in the attic of one of the Underground Railroad operators. Through her only portal to the world, she sees this.

That was inspired by the story of Harriet Jacobs who wrote a famous slave narrative. She ran away from her master and hid in an attic for seven years. But then the modern reader hears that and thinks Anne Frank. So [I thought] how can you talk about slavery and also have it overlap with Nazi Germany? By playing with time, by mixing what was real and not real. It opens up the dialog between Cora’s story and all kinds of oppression at different moments in history.

What’s next for you?

I just finished this [book] in December so I have some time coming and a lot of publicity to do. I have an idea about a book that takes place in 1960s Harlem — very realistic, not a lot of fantastical gestures. So we’ll see what happens when I’m done traveling to see if that’s still interesting.