Advertisement

Review

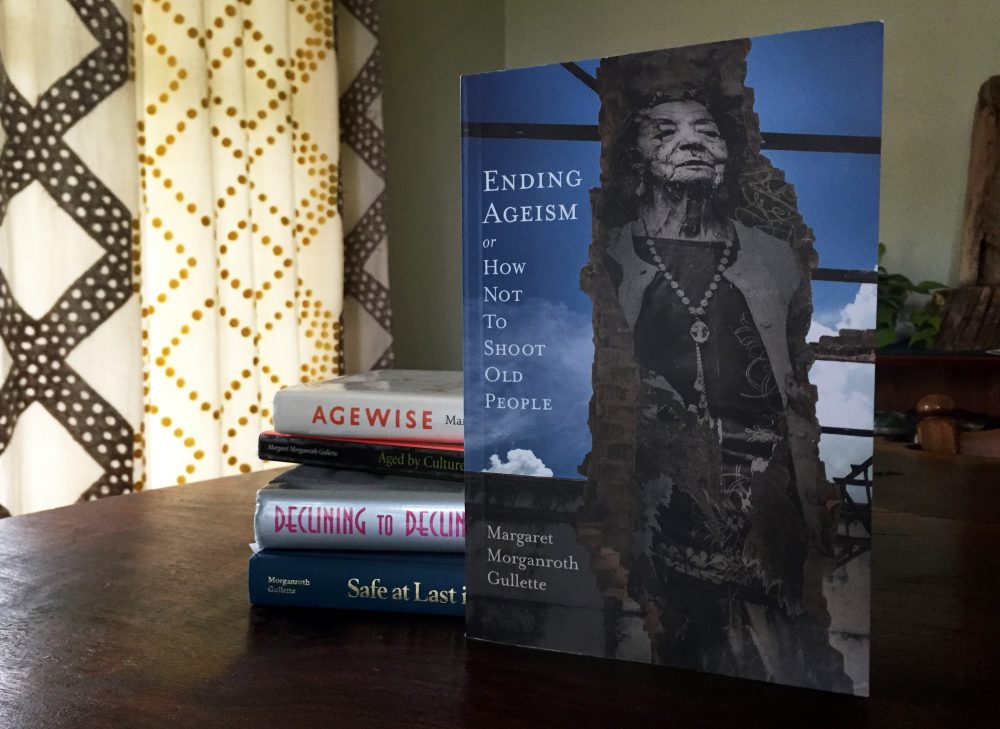

Who Are You Calling Old? Brandeis Scholar Argues For An End To Ageism

Do you know any adult who simply can’t wait to get older? Not likely. Why would someone look forward to losing everything from muscle tone to job security to personal mobility to life itself? Increasingly, that’s our culture’s story of aging. It’s a story of decline.

So says age critic and Brandeis resident scholar Margaret Morganroth Gullette. Through the lens of cultural criticism, and in the field of age studies of which she’s a pioneer, Gullette has been tracking examples of "decline narratives" related to aging, in favor of "progress narratives," for more than four decades.

For her, aging (which she long ago replaced with the word ageism) is the story a culture fashions around the unstoppable process of gaining years. It doesn’t have to be a story of decline. And yet, here we are — at younger ages than ever before — buying remedies, undergoing surgery, feeling shame and otherwise failing to acknowledge the pain we cause ourselves and others when we take what is socially constructed to be biologically inevitable.

“We cannot choose not to be old,” she writes in “Ending Ageism: Or, How Not To Shoot Old People.” She peppers early pages with stats about how "old people" are legion in number, more likely to be rurally isolated and shoulder the brunt of age-based biases in employment, health care and social status. That should be enough for a groundswell reaction, a global social movement against ageism, she asserts. And she certainly wants her newest book to incite action.

This book is intersectional in its approach — and often uses examples from the civil rights and feminist movements — but with those causes under public fire on a near daily basis, anti-ageists have an even steeper climb to gain traction. It’s a tall order and this book's strength lies in its take, or tactics, on topics within ageism more than in a singular ability to mobilize newcomers. (But whether you're past retirement or a millennial, Gullette thinks this topic is relevant for you. We are all headed in the same direction, anyway.)

As part of her call to action, the book’s approach is less academically dense than past books in which midlife novels, first-person narrative, male versus female midlife and the economies of midlife undergo her intense scrutiny. “Ending Ageism” again draws on her expertise in these areas but also expands by tackling global phenomenon such as aging farmers and false claims of a “dementia” defense among elderly war criminals.

Advertisement

Perhaps what will resonate most, at least with non-academic readers, are the practical methods the book offers for spotting ageism. The second chapter, which shares the book's title, goes into detail on how (not) to shoot old people — in portrait photography, that is. Gullette curates a series of evocative images that foster “identification with or desire for, old people.” To uphold the humanity of older subjects, Gullette suggests images that are: Not Naked. Not Headless. Not Clichéd. Not Abjectly Lonely. She also encourages shot composition that offers context to the subject's life and surroundings, depicts plentitude over scarcity, and embraces surprises that foil ageist expectations (such as, 'She's "old" and she's on a swing!'). It's a convincing assortment and analysis.

While devoting a chapter to what some may consider inaccessible or high art, the focus on image creation and reception serves her purpose well. A person who deems someone "old" can shut down that "other’s" character, able-ness and agency with one quick “age glimpse,” as she calls it. Adding to that the cult of youth (millennials at this particular moment, but don’t worry, they too will be replaced soon enough) and the Instagram-ification of what was already a visual culture and you have ample reason to address images as fundamental building blocks to age criticism. Certainly that’s the case in our social-media dominated culture.

One of my favorite photographic examples was taken in Nicaragua by the author’s husband, amateur shooter David Gullette. It’s of Petrona Martínez and what could be her four grandchildren. The author points out that a 15th century Renaissance painter would love the shot’s ennobling touches: a red backcloth frames Martínez’ figure, even though it is off-center; the Madonna blue of her dress picks up other blues on the wall; a winged canopy over her head further accentuates her seniority in relation to the children. Using Gullette’s logic, the image also succeeds by not fetishizing Martínez’ wrinkled skin and not isolating her on a symbolic ice floe.

It’s a lot to ask that one image make an entire case against ageism in a review such as this. Another gem was Kosti Ruohomma’s “Untitled [Couple on Swing]” for its expression of sheer joy and its unexpected scene. Let those serve as appetizers for the lessons in looking (or “not shooting”) offered in this book. In a later chapter on “Fantasies of Euthanasia and Preemptive Suicide,” Gullette calls out Michael Haneke’s 2012 film “Amour” for bringing its viewers into complicity with an octogenarian’s supposed “mercy” smothering of his ailing wife. I couldn’t agree more.

Gullette’s many film references demonstrate her gravity as a film plus age critic and her opinion is worth seeking out. I missed a film she praises for its appropriate treatment of Alzheimer’s and later-life intimacy, “Still Mine,” and now it’s next on my list. (The documentaries “Life Itself” and “Act of Killing” make both of our lists; I’ll add another doc, “Women With Cows,” and the British TV series “Last Tango in Halifax” to boot.) Plus, over her career she’s developed an extensive list of recommended novels.

The chapters on image criticism were undoubtedly more engaging, and convincing, than say, the one on global consequences of farmers' rising average age. I understand the threat of losing farmland to corporations and dwindling farming expertise, but I remain unconvinced that standing against ageism alone is enough to resolve such a complex predicament.

However, when Gullette turns her lens on how human rights violators like Augusto Pinochet or Ieng Thirith have escaped or avoided persecution by using ageist tactics such as trial delays and “dementia” defenses, I was right back in. “A kind of soft ageism can make people sentimental about the unrepented old, even though they have committed mighty evils,” she writes. Because Alzheimer’s is highly feared and hard to diagnose, she explains, “As a nation terrified of memory loss, ours would benefit from watching lawyers…trying to sort out the vast array of conditions scrambled together under the label.” In other words, articulating the fine points of a misunderstood disease in something official like a court of law would do much to alleviate its hovering cloud of anxiety that only grows with age.

Actually, Gullette’s book uses the playful yet serious frame of putting ageism “on trial.” The chapters are presented as sessions for a reading “jury” and the book ends with a declaration of grievances meant to echo the Declaration of Independence and the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments (drafted by Elizabeth Cady Stanton at Seneca Falls). They are bold comparisons but Gullette has done her homework and a lot of heavy lifting to get to this point.

Through her decades of criticism, Gullette often compares ageism to the other isms that have more entrenched, and integrated social movements such as racism, sexism and ableism. Of these, she maintains, “ageism is the least censured, the most acceptable and unnoticed of the cruel prejudices.” If that’s so, the movement has at least one champion with Gullette. But it may take a really long time to coalesce and only do so if we’re lucky. Just like that landmark birthday.