Advertisement

At The Boston Sculptor’s Gallery, An Exhibit Speaks To Wings Clipped Too Soon

Christina Zwart became friends with sculptor David A. Lang when she needed help with a sculpture she was working on. She had recently met Lang at a party and thought he might be just the person to call for advice.

“I said, 'I need something that can make a horseshoe crab tail go back and forth in the back of a box.’ Honestly like it was the most normal thing in the world, he said, ‘Oh, come on over to the shop.’ I had never been to his shop… I drove straight there and literally he dropped everything he was doing and spent about three hours building this crazy wire contraption in the back of a box to make the tail do what I wanted it to do.”

A Wayland sculptor known for his mischievous and chimerical kinetic sculptures, Lang was a natural person to approach about what others might consider an odd problem. His Natick studio was a little bit like Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, chock full of sculptures and capricious inventions reflecting his far-reaching flights of fancy. There he created some of his best-known works, like the combat boots, heavy and rough, equipped with a pair of dainty gossamer wings that flap delicately, or the teasing little clam shells that open just wide enough to reveal a little surprise inside before snapping shut.

“Then we just started hanging out together all the time and it was totally fantastic,” recalls Zwart. When Lang recommended that Zwart apply to The Boston Sculptors Gallery cooperative in the South End, she did, and was accepted.

Lang, a 76-year-old artist who enjoyed a long career showing his kinetic sculptures at local art associations and regional museums throughout New England, died late last year after a deer was thrown into the windshield of his vehicle, causing it to flip. His unexpected death was a significant loss to the Boston art community in which Lang was well-known, not only for his sculptures, but for his mentorship, his humor and his teaching.

Now, his work will be on display at the Boston Sculptors Gallery from Dec. 12 through Jan. 27 (along with the work of Jessica Strauss), in an exhibit that fills a slot in which he would have normally shown his most recent work at the South End cooperative. The show was coordinated by Zwart and curated by Katherine French, formerly the executive director of the Danforth Art Museum in Framingham, where Lang himself was also a founding member back in the 1970s. French, now gallery director at Catamount Arts in St. Johnsbury, Vermont, says she was first introduced to Lang through his art, specifically a large metal sculpture on the grounds of the Danforth Museum where she began working in 2005. Over time, she got to know Lang personally when he attended opening receptions or helped out with Danforth’s educational programming.

“David was both serious and whimsical,” reflects French. “In his own words, he was ‘accidentally profound.’ I liked the intelligent, formal composition of his work, as well as the equally intelligent ability to use them to display his humor and wit."

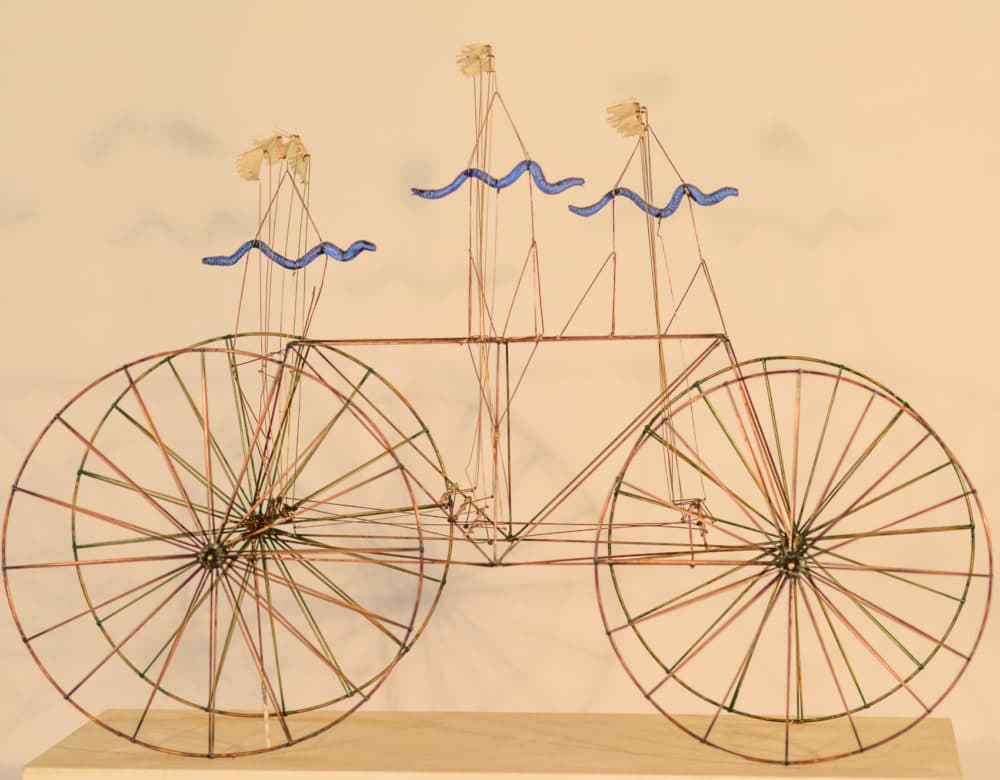

On view will be 19 of Lang’s quirky sculptures, including “Odysseus,” one of two winged boot sculptures that Lang created. The boots came from a friend who served in the Korean War and Lang was taken with them. He loved, he said, the rough texture of the boots and the grace of the wing movement.

“I just thought the anchoring and the grit, and the involvement of these with battlement and the purity of the wings complemented one another quite well,” he said in a video about the piece made while he was alive.

Sometime after the sculpture was made, he read how Odysseus, returning from battle, had always maintained his loyalty to his wife.

“I had no idea that’s what the piece was about until it was finished,” mused Lang.

In fact, that’s how it often worked. He followed his curiosity wherever it might lead, pushed along by whatever interesting materials might happen to spark an idea. At the end of tinkering and playing around, often only after the sculpture was completed, he would realize what the sculpture was about.

Lang grew up on Long Island in a household that he said was filled with machines, parts and pieces. His father was an engineer, metallurgist and inventor, and Lang, who worked for his father during summers off from school, inherited a passion for tinkering which he said came to him "naturally."

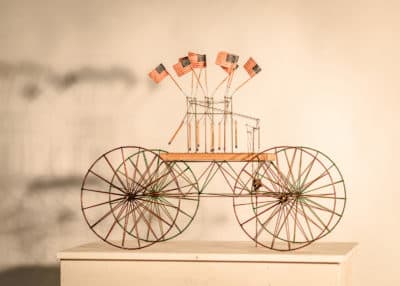

After graduating from Fairfield University where he studied biology and art concurrently, he enrolled in a Medical Illustration program at Massachusetts General Hospital. After working at Harvard’s Department of Chemistry in scientific illustration, Lang went on to teach at Middlesex School in Concord, where he would become chairman of the art department and work for the next 30 years. In the last 10 years of his tenure there, he began to rebuild British sports cars with his students. The rebuilding of broken down motors was just a continuation of a passion that would later surface again in his kinetic sculptures that are often activated by small motors and cranks. His pieces revel in mechanical inner workings, which in his work become performative outer workings. In full view are wires, wheels, cranks, weights, gears and other assorted mechanisms that exude a frangible beauty. Along with a sort of reverence for the mechanical, there is often a cheeky sense of humor too.

One of his pieces, “The Day the Castinetti Sisters First Learned to Fly,” consists of five clam shells, held aloft on slim wires. Each clamshell has wings that flap thanks to cranks and gears. The clam shells open and shut in a pattern that takes hours to repeat. Lang enjoyed surprise and fun. In this work, it is only when you get up close and take a good look that you glimpse a naked woman inside before the shell snaps shut.

Another playful piece is "Straight Eight" — eight pairs of scissors atop a carriage-like metal structure of four wire wheels. The scissors strain to cut pieces of paper that hang tantalizingly out of reach. Lang devised this sculpture after finding a dozen pair of children’s school scissors on sale. He didn’t know what he would do with them, but after a couple of months he realized he wanted to have the scissors open and close in sequence. He used lead fishing weights to help pull the scissors open, but he wanted the sculpture to do more. That’s when he hit on the idea of adding little bits of paper that the scissors would attempt to cut but never quite reach. Inherent in the piece, said Lang, was the notion of just barely escaping something. Viewers tend to root for either the paper or the scissor but rooting or wishing doesn’t change the outcome of the piece.

“I liked his sense of humor,” says Zwart. “We liked the same sort of weird materials. He was avuncular and Geppetto-like. He would say, 'Let's read out of David Sedaris today,' and we would read from one of David Sedaris' books and just laugh our heads off. I'd come over to the studio and he'd be wearing hot pink reader glasses because he liked them, and they had rhinestones on them. He was very funny but very, very serious about the work when it was time to get down to business.”

Most of Lang’s pieces have wheels, which he said represented the passage of time, or moving from one place to another place, or even standing in time. His art was very much about playing, process, enjoying and reveling in the unexpected. A piece might start out one way and go in another direction entirely.

In that way, his work was a lot like life.

Exhibitions of David A. Lang and Jessica Strauss' work are at the Boston Sculptors Gallery from Dec. 12 to Jan. 27. An opening reception will be held Saturday, Dec. 15, from 4 to 7 p.m.