Advertisement

Somerville Theatre's Jack Nicholson Retrospective Spotlights An Earlier, Angrier Side Of Hollywood’s Class Clown

“There is James Cagney, Spencer Tracy, Humphrey Bogart and Henry Fonda. After that, who is there but Jack Nicholson?” director Mike Nichols once famously asked. The movies’ most mischievous superstar turns 82 next week, and in celebration the good folks at the Somerville Theatre have programmed “Jack Attack!” — a marvelously comprehensive retrospective that runs through October, featuring 37 films from a career that’s spanned nearly six decades.

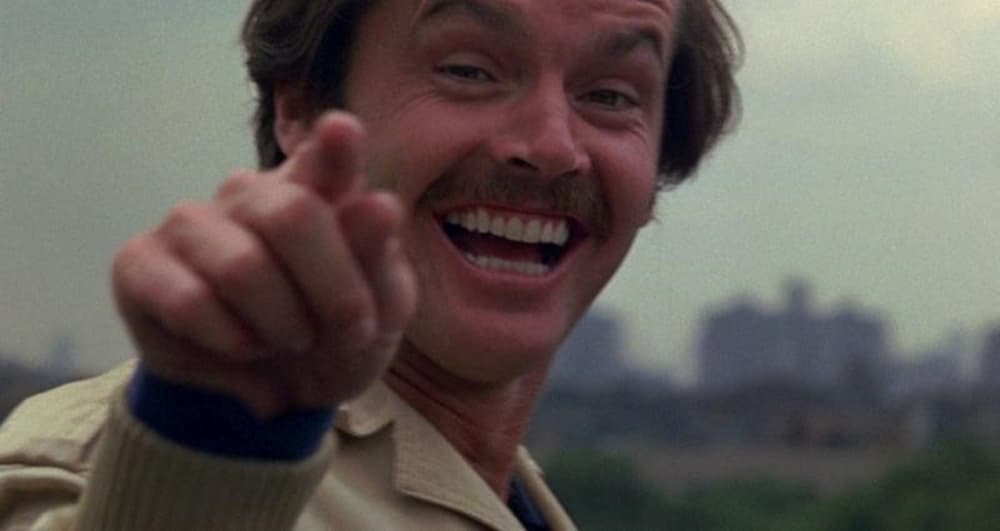

When we think of Nicholson these days we tend to think of the icon: those up-ticked, ambidextrous eyebrows peeking out over the top of his omnipresent shades, or the slow unfurling of that wolfish, conspiratorial grin. Courtside at Lakers games and front row at the Oscars, nobody’s ever having more fun than Smilin’ Jack, the porky satyr leering with a Cheshire smile of self-delight. Women, drugs and a freewheeling, leftover 1960s hedonism are all part of the playful persona — the Joker as Hollywood’s class clown.

But there was a remarkable five-year run at the beginning of his career when Jack Nicholson embodied something else entirely. 1970’s "Five Easy Pieces" — screening at the Somerville this Friday, April 19 — set the template for a new kind of leading man, an updated anti-hero seething with self-loathing and discontent. For the first half of that confused, angry decade Nicholson deftly articulated a generational malaise — stewing in the juices of swaggeringly macho characters coming to realize the extent of their own impotence, film after film a study of failure.

Nicholson had been knocking around for more than 10 years as a jack-of-all-trades (sorry) working on low-budget westerns, motorcycle movies and horror flicks for legendary exploitation mogul Roger Corman, finding some success writing screenplays for hippie freak-outs like 1967’s “The Trip” and The Monkees’ surrealist 1968 romp “Head.” (He and director Bob Rafelson notoriously picked the title for the latter just so they could advertise their next collaboration as “From the people who gave you ‘Head.’ ”)

It was only after Rip Torn got into a fight with Dennis Hopper that Nicholson was chosen as a last-minute replacement for the scene-stealing role of doomed square George Hanson in 1969’s seminal “Easy Rider.” Producer Bert Schneider reportedly hoped his pal Jack would be a steadying influence on director Hopper and star Peter Fonda, which should give you some idea of how the production was coming along.

Though hardly convincing as a guy smoking pot for the first time, Nicholson’s rascally, mega-watt charisma gives the rather logy movie a huge energy boost — I always lose interest following his untimely exit — and after over a decade of false starts a star was finally born. (As a nice touch, the Somerville series closes with “Easy Rider” on Friday, Oct. 11, ending with what turned out to be the beginning.)

The surprise blockbuster success of "Easy Rider” allowed Schneider to bankroll a series of difficult dramas through Columbia Pictures, the first of which was “Five Easy Pieces.” Directed by Rafelson from a spiky screenplay by Carole Eastman, the film stars Nicholson as Bobby Dupea, a piano prodigy turned prodigal son from a wealthy classical music dynasty, who we first meet working as a roughneck in the California oil fields.

It’s almost a third of the way through the movie before we learn about the aristocratic background that Bobby has renounced. Until then it’s all trailer parks, bowling alleys and drunken bellowing, with our protagonist verbally abusing and casually catting around on his knocked-up, dim-bulb, diner waitress girlfriend Rayette (a heartbreaking Karen Black) who blasts Tammy Wynette records all day at deafening volumes while choking back tears.

Nicholson gives a galvanizing performance as a drifter who knows no tribe of his own, forever ill at ease. Bobby’s both attracted to and repulsed by Rayette — Black is fearlessly, at times unbearably, annoying — and his sudden eruptions of contempt for her only serve to remind him that he hasn’t shaken off nearly as much of that snobby, upper crust upbringing as he’d like to think he has. This naturally engenders even more resentment in a destructive cycle that is in no way alleviated by the character’s keen intelligence and self-awareness. Or as Bobby himself puts it, “I move around a lot because things tend to get bad when I stay.”

Bobby Dupea’s penchant for disappearing acts is echoed in “The Passenger,” which screens at the Somerville on Sunday, May 5. Michelangelo Antonioni’s moody 1975 existential thriller is one of Nicholson’s favorites — he personally bought the rights to the picture and recorded a whispery humdinger of an audio commentary for the DVD that begins with his smoky voice purring, “This is what used to be known as an art film.”

Confounding to critics and audiences at the time but rightfully reevaluated after a 2003 restoration and re-release, the film stars Nicholson as a sullen journalist on assignment in North Africa who abruptly and without explanation steals the identity of a guy in the hotel room next door — a British gun runner who died of a heart attack. “The Passenger” has all the elements of an action movie but remains stubbornly, intractably static. As always, Antonioni is more interested in emptiness, the vast, barren landscapes an externalization of the void inside our protagonist.

The film’s legendary penultimate shot finds a harrowingly hollowed-out Nicholson alone in another rented room that looks suspiciously like a prison, while a world beyond the barred windows carries on oblivious to the plot mechanics going on inside. The point is you can travel around the globe and pretend to be whoever you want to be, but when it all comes to an end you’re still locked in with nobody but yourself.

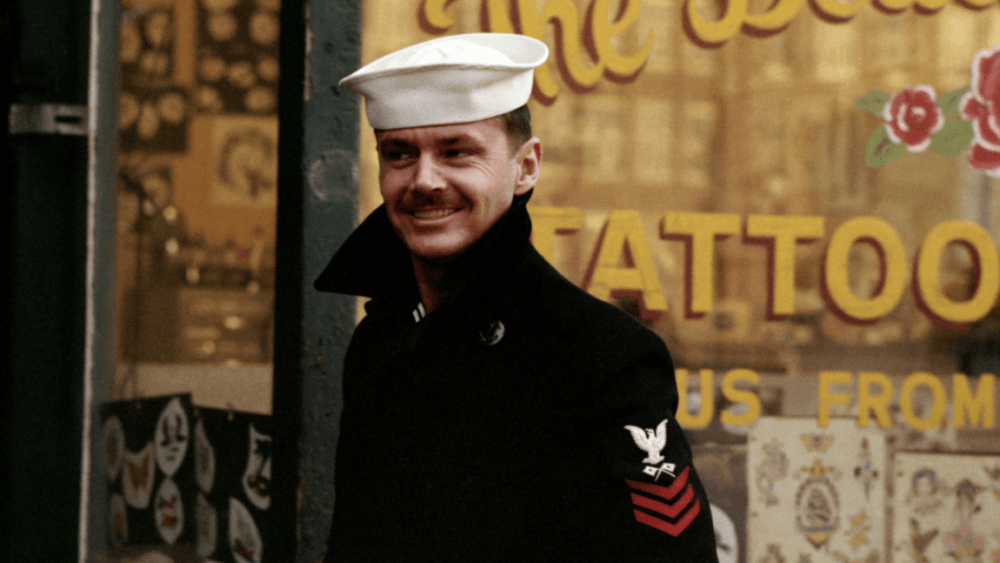

My favorite Nicholson performance is his macho blowhard Navy Signalman First Class Billy “Badass” Buddusky in director Hal Ashby’s 1973 masterpiece, “The Last Detail.” Screening at the Somerville on Saturday, May 4, this bleak and beautiful road movie sends Nicholson’s foul-mouthed braggart and Otis Young’s soulful sidekick on assignment to escort a wet-behind-the-ears swabbie (Randy Quaid) from their base in Virginia to the brig in New Hampshire, where the kid is set to serve eight years for swiping 40 bucks from a charity box.

Nicholson is all moustache and bluster here, picking fights and busting chops with a hollow braggadocio that’s almost completely full of beans. He decides he’s gonna show their prisoner a good time before sending him off, getting the kid drunk and laid under increasingly unseemly and pathetic circumstances. It’s a larger-than-life role that grows smaller and sadder as the movie wears on, gradually revealing the limitations of Buddusky’s bravado and the fears that churn beneath it.

Ashby keeps the characters outdoors as often as possible, shivering under a pale winter light. Robert Towne’s screenplay caused a fair amount of controversy for letting these sailors curse like sailors, but the bad behavior and voluminous profanity are necessary for being the only outlets these men have. Everything else is owned by the Navy. The film’s final moments find Nicholson at his most emasculated and ineffectual — the way he ended so many of these magnificent early pictures — sputtering obscenities into a cold, indifferent wind.

“Jack Attack!” runs through October at the Somerville Theatre.