Advertisement

'WBCN And The American Revolution' Cements The Radio Station's Place In Music History

It’s been a decade since WBCN rode Boston’s airwaves. In mass media terms, that’s an eternity. Today, if you tune to its old spot on the FM dial, you’ll hear a “hot contemporary adult” format, Mix 104.1, a world away from what once was.

For many years — anywhere from 1968 to 2009, depending on when you lived here and tuned in — 104.1 meant rock and WBCN. Locally prominent and nationally influential, WBCN became many things over the years: a station that broke acts from the Cars and Tom Petty to U2 and Radiohead, a ratings powerhouse in the ‘80s and ‘90s and a money-making machine for its eventual owners, Infinity Broadcasting and CBS. During the first decade of this century, it began to fade.

But the formative years are the focus of producer/director Bill Lichtenstein in his two-hour documentary, “WBCN and The American Revolution.” The film, 10 years in the making, screens Saturday, April 27 at the Somerville Theatre, the Centerpiece Spotlight Documentary at the Independent Film Festival Boston.

Yes, the old Grateful Dead line applies: "What a long strange trip it’s been…"

Ray Riepen took over programming from T. Mitchell Hastings and scrapped a faltering classical format. He bought stock in the company and later sold the stock when he left town in the early '70s. (Hastings sold WBCN in 1979 to the group that would later become Infinity Broadcasting.)

He processed the numbers — 250,000 college students and 84 colleges in metro Boston — and responded with a free-form maelstrom of music and chatter. Soon to go 24/7, it was peopled by amateur DJs who’d been at Boston area college stations. They chose their music and were encouraged to ruminate. It was a radical concept. FM radio, though possessing much better sound than AM (and in stereo to boot), was virtually a non-entity. Top 40 was the coin of the realm then; at a radio convention, fellow executives told Riepen he was nuts.

As it turned out, he was prescient. WBCN was a case of the right time, right place, right sound, right attitude. They broke rules and they broke artists such as Aerosmith and Bruce Springsteen. Because they were playing in town — not because any record company booked it or WBCN promoted it — Jerry Garcia and Duane Allman dropped by the station and had a two-hour on-air jam. No one thought to record the session.

Advertisement

WBCN was at the forefront of a national radio format evolution. Stations like KSAN in San Francisco and WNEW in New York had adopted similar formats. They later spread across the land, variously called “progressive” radio and, then, over time, the more restrictive "AOR" — or album-oriented rock.

While the creation and the no-roadmap development of WBCN is the focus of the documentary, Lichtenstein’s intent is to also show how the station’s music and politics were very much woven into the turbulent tenor of the times. WBCN’s motto was, indeed, “The American Revolution.”

When WBCN launched, there was the hard rock of Cream, Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa, but also the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, the Chicago riots at the Democratic convention, the Vietnam War and the raging protests in the streets.

News, initially non-existent, became an integral part of the station’s identify, especially under Danny Schechter, who opted for the designation of “news dissector” over “news director.” (Schechter is one of three voices in the film who have died; DJ J.J. Jackson and photographer Peter Simon, the others.) WBCN news was often news delivered with a liberal bent and activist sensibility. “A different point of view,” said left-wing MIT professor Noam Chomsky, succinctly. “A unique and courageous voice.”

It became a community resource, with everything from a volunteer-staffed listener line — trying to solve listeners' problems or answer queries — to a Cat and Dog Report (who’s missing? who’s been found?). In the film, program director Norm Winer called it the internet of its day.

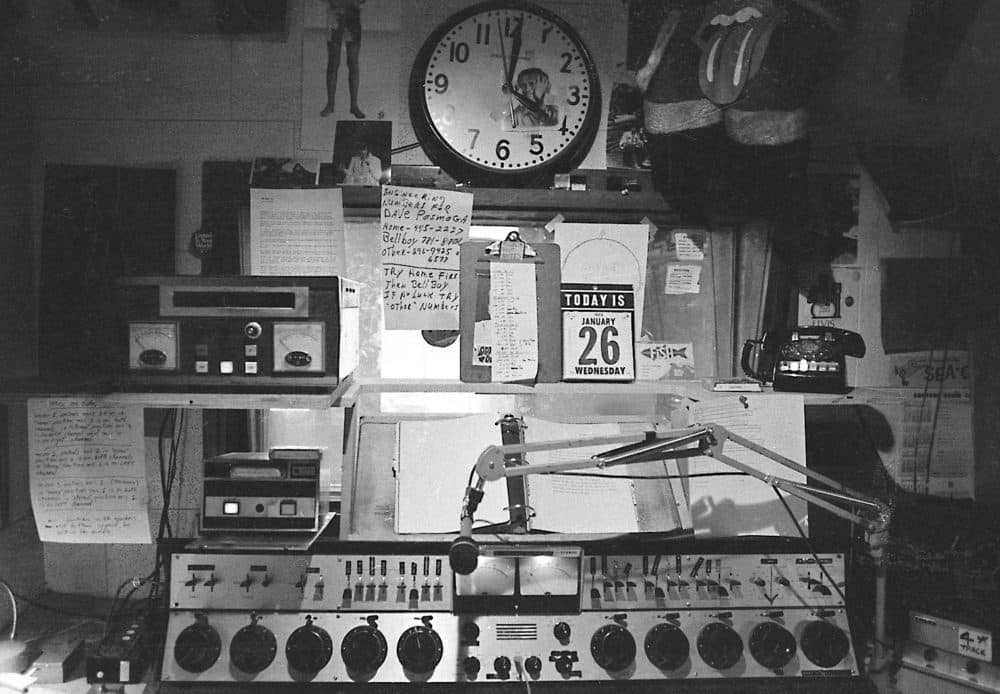

As happens with some Ken Burns docs, Lichtenstein — who started as a 14-year-old intern and eventually became a DJ and newscaster — was visually limited because WBCN existed way before amateur video became ubiquitous. Heavy film equipment wasn’t prevalent or handy and no one was thinking documentation or permanence anyway. Everything happening was very much in the moment and was of the moment.

As such, while there’s action footage from the TV news broadcasts, WBCN’s story is mostly handled via still photographs (there are many archival shots), audio snippets, short bursts of contemporary music, and look-backs from some of the principal players.

There are 36 of those, chief among them WBCN’s longest-running star being the quick-witted and politically active morning drive DJ Charles Laquidara, who was one of the first professionals to join the staff, in November of 1968. (He took what he refers to as a “cocaine vacation” 1976-1978, came back and then moved to sister station WZLX to make way for Howard Stern in 1995.)

There are snatches of rapid-fire on-air bits from original overnight DJ (and J. Geils Band singer) Peter Wolf, but he opted not to be interviewed for film. As did Maxanne Sartori, WBCN’s best-known female DJ, credited with having great “ears” and giving Aerosmith its first major airtime via repeated plays of “Dream On.”

Sartori, and other women, came aboard after a flip comment on the air from Laquidara about “chicks.” That prompted a women’s liberation protest and a management decision to increase gender diversity on the staff. Among other ground-breaking moments: At first, WBCN only accepted local advertising from businesses compatible with the station’s image. (That changed in 1974.) Jackson was among the first black DJs on the FM rock radio dial. In 1973, just three years after the Stonewall riots, WBCN launched a weekly gay and lesbian show, “The Lavender Hour” with John Scagliotti and Andy Kopkind.

Does Lichtenstein’s film paint a rosy picture of those times? Yes and no. It was certainly a heady time for rock radio and rock fans; the tight playlist of Top 40 was shed and the music was taken more seriously. But these were tumultuous times for America and Lichtenstein’s inclusion of cataclysmic events into the narrative, thrusts us back into those.

The film pretty much ends in 1974, following President Nixon’s resignation, but there’s a juicy coda — and one of the most exciting moments in the film — from January 1976. Patti Smith and her band are playing the Jazz Workshop club. It’s Smith’s first radio simulcast and she wonders aloud whether she can use certain profane words during her song “Birdland.” She ultimately decides she can and WBCN can do whatever they want with it. WBCN let it fly. There would have been jobs on the line had someone complained to the FCC. No one did.

"WBCN and The American Revolution" has its East Coast premiere during the IFFB on April 27 at the Somerville Theatre.