Advertisement

Review

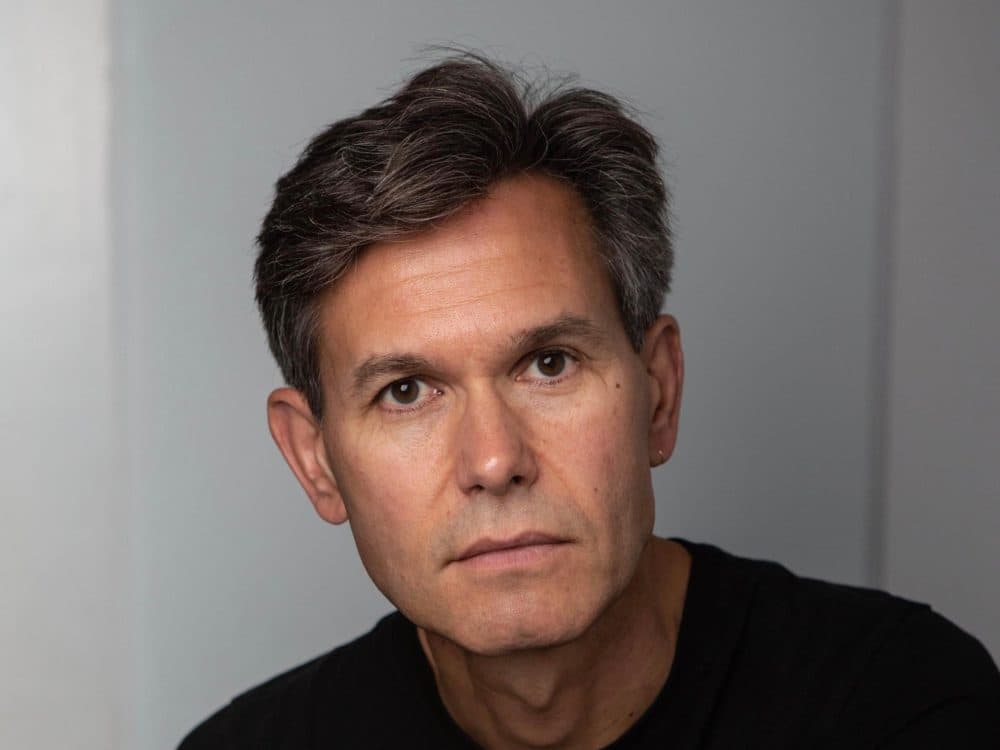

A Somerville Writer Conjures The Last Humans' Life In 'The Bear'

In his latest novel, “The Bear,” Somerville-based writer Andrew Krivak tells the story of the last two people on Earth, a father and daughter living in a resurgent wilderness long after the collapse of human civilization. However, despite the book’s post-apocalyptic setting, Krivak eschews the bleak, dystopic mood common to the genre and opts for a more thoughtful, meditative exploration of humanity’s place in the world.

Several generations have passed since the world as we know it ended, and the two remaining humans know very little about what came before them. They cling to a few precious artifacts that have been preserved and passed down to them by their ancestors: a single pane of glass; a silver comb; and a few moldering books, including the works of Virgil, H.D. and Wendell Berry. They eat only what they can kill, trap or gather themselves; they wear only what they can make with their own hands. But their lifestyle, though humble, is not one of privation. They have achieved a delicate balance with their surroundings, synchronized to the rhythms of nature, the phases of the moon and the changing of the seasons.

“He taught her how to take sinew from and tan the hides of deer he had shot with a selfbow made of hickory. How to hunt for swarms of wild honeybees when the goldenrod bloomed before the autumn equinox, and how to take honey from the tree where those bees had built their hive… When the nights were clear, he took his daughter outside and taught her how to look at the sky, pointing to the stars along the ecliptic and telling her the names of the constellations that traveled there,” Krivak writes.

Shortly after the girl turns 12, the pair set off on a long journey to the ocean, where they intend to extract salt from seawater for use in preserving meat. Along the way, the father stops to scavenge for useful items in the ruins of an old neighborhood and is bitten by a rat. His wound becomes infected and in short order he dies, leaving his daughter to make her way back to their camp alone, the last human being who will ever live.

The path back is long and arduous. Wracked by grief, and with winter fast approaching, the girl is unsure she can make it to the relative safety of the cabin on her own, and even less sure of what her future holds once she does. But out of the forest, a bear emerges carrying a fat river trout and offers it to the girl. “You need to eat,” he says, “if we’re going to leave here.”

Together, they travel through the forest, collecting food, navigating obstacles and discussing her plight. The bear is part guide, part therapist, helping the girl process her feelings while reminding her that she has the skills to survive. And the bear is not her only guardian. At one point, ignoring the bear’s advice, she ventures out on her own to cross a frozen river while her traveling companion is lost in the depths of hibernation. When she plunges through the ice, she is rescued by a puma, which drags her from the water and brings her back to the bear’s cave.

Both the bear and the puma feature in stories her father told her as a child, and she wonders whether their appearance might be “a trick of the mind or apparition.” But she soon comes to believe in their reality and, as the book progresses, it becomes clear that Krivak does, as well.

Though the premise of “The Bear” invites comparison’s to Cormac McCarthy’s 2006 novel, “The Road,” there are some marked differences. McCarthy’s apocalypse annihilates the natural world, leaving behind an unlucky mass of humans to fight over what little remains. It’s a story about what we could lose, materially and spiritually, if society continues down its dark path. “The Bear,” however, asks us to consider that we may have already lost something; and that, as a species, we may have lost it so long ago that none of us alive today are capable of truly understanding how significant a loss it was.

When the girl asks how the bear can communicate with her, he explains that “…all the animals knew how to make the sounds the girl and the father used between them. But it was the others like her who stopped listening and so the skill was lost… Not all animals had the range of voice that could be heard, he said, but all living things spoke, and perhaps the real question was how she could understand him.”

Krivak’s post-apocalyptic future is a throwback to a pre-industrial, pre-Anthropocene culture, in which humanity is not master of its environment but instead just another facet of it, beholden to its bounty and subject to its whims. It’s an idyllic, but not idealized, depiction. The father’s grim death is proof enough that the natural world is no Arcadian paradise. But through the girl, Krivak enables us to see the world through different eyes – to be able to discern the differences between birch and dogwood and hemlock, to read landscapes of broken limbs and overturned leaves, to recognize a million little meaningful details and distinctions that would otherwise pass us by, the signs and symbols of a language we no longer recognize.

In his lush, lyrical descriptions, Krivak presents his wilderness as awful in the archaic sense of the word – a captivating blend of terror and beauty. In this, the book recalls Adalbert Stifter’s luminous novella “Rock Crystal,” in which two young children become lost upon an Alpine glacier while traveling home on Christmas Eve. The two books share a deep and almost religious reverence for the majesty of nature, as well as a spare prose style that gives the stories a familiar, fable-like feel, as if they’ve been with us since the beginning of time.

Indeed, after the loss of the girl’s father, the story seems to drift toward the realm of myth and legend. The appearance of the bear and the puma, which emerge from her father’s stories and into her reality, as well as the girl’s slow shedding of the material vestiges of civilization, mark the girl’s entrance into a new state of being, one that is wholly unrecognizable to us.

At times throughout “The Bear,” I wrestled with whether I was meant to take what was happening literally or metaphorically; ultimately, I recognized I was asking myself the wrong question. I was simply meant to take it, to think on it, and to try to imagine a different way of seeing the world.