Advertisement

Commentary

Reflecting On The Legacy Of 'Goodfellas' 30 Years On

The movie that changed my life turns 30 years old this month.

It was a cool September evening in 1990 when two carloads of high school friends and I went to the Showcase Cinema in Revere for opening night of Martin Scorsese’s “Goodfellas.” The theater was kind of a dump back then and most of the screens were still in mono, but we preferred the place because they never carded kids for R-rated films and if you were sneaky enough you could see two or three movies on one ticket. It was also located across the street from a sleazy strip club and notorious mob hangout — whenever we drove by on the way to the airport my dad would tell us kids to “count all the Cadillacs at The Squire” — which is something that didn’t dawn on my buddies and I until the film began and we realized we were probably the only guys in the auditorium that night who weren’t connected.

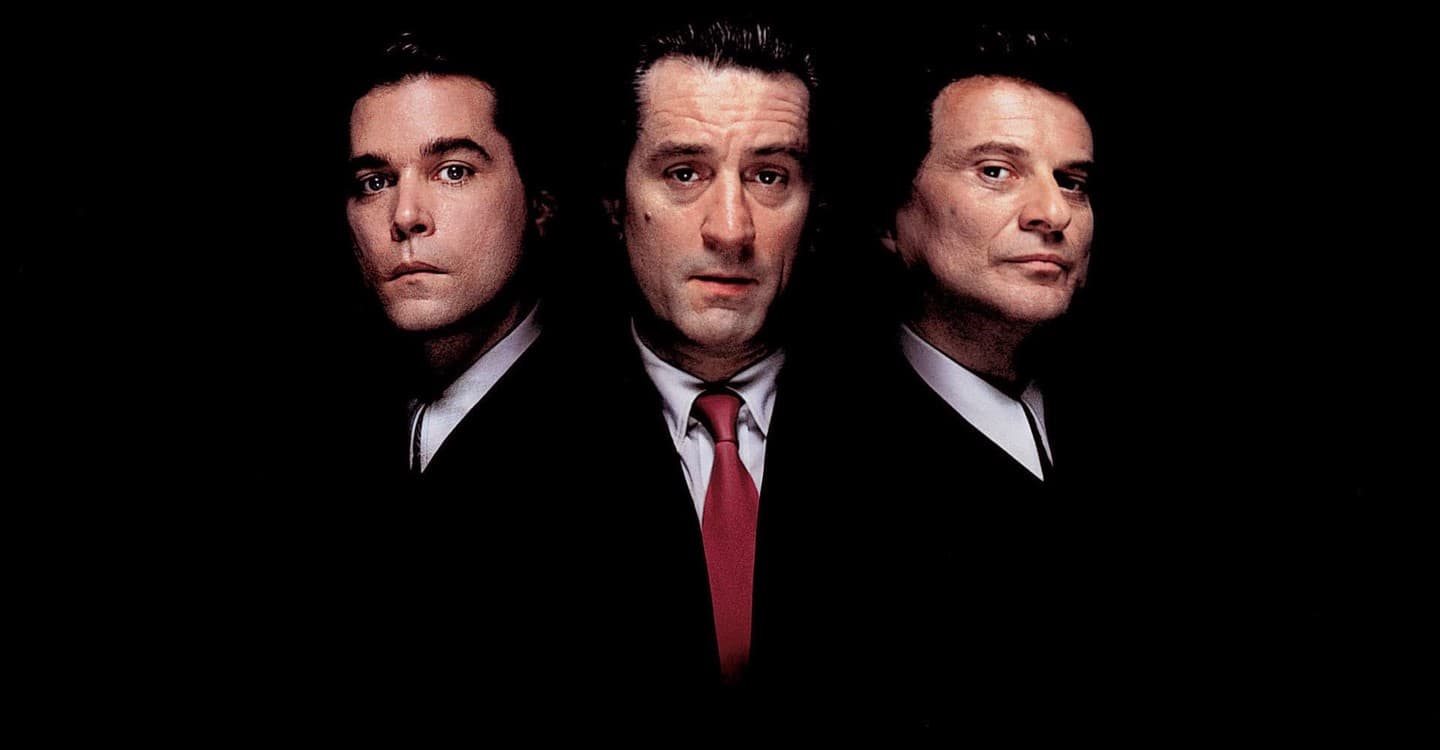

“THAT’S ITALIAN!” someone in the audience bellowed at the sight of Robert De Niro’s name in the opening titles, to uproarious applause. This followed for every name in the credits that ended with a vowel, which as you’ll recall are quite a few. And then after that grisly prologue — in which Joe Pesci leans into the car trunk with a kitchen knife and repeatedly stabs a bloody, whimpering Frank Vincent, followed by De Niro emptying his pistol into the corpse — once again the guy hollered “THAT’S ITALIAN!” and the theater exploded into cheers. Watching “Goodfellas” with that crowd was a fully interactive experience, like “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” for felons. But I was so exhilarated I barely noticed.

As a kid, I had always been crazy about movies, but at 15 years old I was just starting to understand what a director did and how films were made. “Goodfellas” hit me like a bolt of lightning. It’s the most sustained act of showboating virtuosity in American cinema since “Citizen Kane,” or at least “Touch of Evil.” Chronicling the rise and fall of unrepentant lowlife Henry Hill, Scorsese constructs the film at first as a seduction, with soaring camera movements and side-splitting comedy, followed by a nerve-shattering collapse during which all the allure of this lifestyle is revealed as rotten to the core. He and editor Thelma Schoonmaker set a dizzying array of whip pans, slow motion, Steadicam shots and jump cuts to a nonstop soundtrack of jukebox oldies as if exulting in the sheer, delirious possibilities of what movies can do.

So much of “Goodfellas” has been absorbed into popular culture over the past three decades it’s sometimes difficult to remember just how radical — even dangerous — it felt back then. Scorsese gleefully tears down the opulent mythology of “The Godfather” with a parade of numbskull proles meeting ugly ends. Working from Mafia foot soldier Hill’s confessions to reporter Nicholas Pileggi in the 1985 bestseller “Wiseguy,” the film depicts the workaday realities of organized crime with a documentarian’s eye for detail and the sneer of a class clown sent to detention. So irreverent it ends with Sid Vicious’ sarcastic cover of the flatulent Sinatra anthem “My Way,” I’d never seen a movie with such swagger. The attitude is contagious. When you watch it you feel like you’re getting away with something.

Just in time for the film’s 30th anniversary, former Premiere magazine editor and New York Times film critic Glenn Kenny has published “Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas,” an exhaustive and essential companion piece to the picture that taught even this self-proclaimed expert a ton of new things about his favorite movie. (I read all 397 pages in basically one sitting.) Kenny first interviewed Scorsese back in 1989 when the director was cutting the picture, and any fan of his writing — especially his excellent 2014 book “Robert De Niro: Anatomy of an Actor” — knows this is a project for which he is particularly well-suited.

Advertisement

The bulk of the book is a scene-by-scene walkthrough of “Goodfellas” annotated by interviews with the principals, production anecdotes and Kenny’s characteristically astute analysis. Reading it is like watching the movie again while sitting next to the smartest person you know. Deftly balancing the true crime lore with Hollywood history, “Made Men” places the picture within the context of Scorsese’s career and those of his collaborators, correcting more than a few popular misconceptions. “Goodfellas” is now comfortably enshrined as a classic from one of America’s most revered artists, but at the time, it was an extremely risky proposition from a financially unsuccessful director with a difficult reputation. The first time the film was test screened for an audience in Encino, 42 people walked out during the opening scene. (Presumably, none of them shouting “THAT’S ITALIAN!”)

It’s become common lore that Joe Pesci’s immortal “What do you mean I’m funny?” speech, during which he terrorizes Ray Liotta’s Henry by repeatedly asking, “What am I, a clown? Am I here to f---in’ amuse you?” was an improvisation by the actor, based on something he saw a real gangster do back during his days on the shady fringes of the music industry. But what a lot of folks don’t realize is that Scorsese’s approach to improv is not the contemporary Judd Apatow or mumblecore style, where directors turn on the cameras and allow the actors to just riff. He works in the mode pioneered by John Cassavetes, in which such contributions are worked out in rehearsals, re-written and incorporated into the plan for the film. They don’t just make this stuff up while they’re rolling.

The speech was not, however, in the shooting script originally approved by the studio. So when Warner Bros. exec Terry Semel — a bit of a figure of fun in the book for his idea that Tom Cruise and Madonna should play Henry and Karen Hill — made a surprise visit to the set that day he was furious to find Scorsese burning time and money on an unauthorized scene. As punishment, he pulled permission for the production’s trip to Florida to film the sequence in which De Niro and Liotta dangle a debtor over a lion’s den, an obstacle deftly overcome by the crew shooting at the Bronx Zoo instead with a couple of well-placed palm trees and a sign that said “Tampa” on it. That was the studio’s first reaction to seeing the scene that most likely won Joe Pesci an Academy Award.

“Made Men” is full of fun little stories like that, and Kenny understands that “Goodfellas” works so well because of its massive accumulation of minute details. There are few films that feel so lived-in, with the anthropological precision of its tacky furniture, bad fashions and the emphasis on food feeling almost like an extension of Scorsese’s 1974 documentary “Italianamerican.” (Both movies are stolen by his mom.) The storyline includes what turned out to be the biggest heist in American history, and yet Scorsese doesn’t even bother showing it. Instead, it’s a movie about the day-to-day grind, set in drab diners and dingy bars. The film’s fixation on mundanity finally comes to a head during the showstopping sequence during which Henry’s trying to run errands, sell guns, smuggle drugs and prepare an elaborate family dinner in the midst of a cocaine meltdown. All the felonies he’s committing are given equal weight and importance as stirring the tomato sauce, just more tasks on the to-do list. (Kenny includes the recipe for Henry’s sauce in the book, warning that it might cause meat sweats.)

The frenetic technique on display in this set-piece is the closest a lot of audiences will ever come to feeling coked out of their gourds, with the herky-jerky camerawork, jumpy cutting and buzzing classic rock songs putting you inside the protagonist’s frazzled headspace. (It’s notable that there’s no more music in the movie after Henry gets arrested.) When Schoonmaker received the Coolidge Award in 2007, I had the great privilege of attending a master class during which she went through this sequence with a laser pointer, stopping and starting scenes to discuss the intricacy of the audiovisual design and everything they intended to convey. A friend working at the theater said she’s never seen me happier than I was that afternoon.

There’s a shot about three-quarters of the way through the film when De Niro sidles up to a bar, smoking a cigarette as Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love” kicks in on the soundtrack. The camera creeps up on him, with Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus shooting at 32 frames per second instead of the usual 24, lending the image a sinister slowness. With what would otherwise be an almost imperceptible flick of his eyes around the room, De Niro gives his whole plan away, letting us know he’s going to whack the rest of his crew and keep all the money for himself. I can still vividly remember sitting in that theater 30 years ago, because that moment crystalized for me how lens choice, camera movement and music cues could tell you a whole story without anyone saying a word. It was when I first understood what it meant for a film to be directed. It's no exaggeration to say that night is why I decided to go to NYU — because that's where Martin Scorsese went — and it's why I'm a film critic now instead of an adult with a responsible profession. "Goodfellas" gave me the high I've been chasing at the movies ever since.

Glenn Kenny’s “Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas” is now in bookstores.