Advertisement

Future Of Work

How A Robot Is Changing Furniture Making At A Factory In Fitchburg

This story is part of a BostonomiX series called “The Future Of Work” that examines the jobs of the future and the skills needed for those jobs.

Furniture runs in Josh Weissman's blood. In 1976, his dad started the company Moduform, which he now owns and operates. The Fitchburg-based furniture-maker supplies nightstands, beds, chairs, desks and more to college dorms and hospitals.

"Back in the '80s and '90s, we had craftspeople," Weissman said. "Because in this neck of the woods, in north-central Massachusetts, it was a haven for furniture."

Decades ago, when his dad first created this factory, Weissman says there was a sizable pool of people regularly looking for work in the furniture-making market. But times have changed.

"Trying to find people that want to do this work is very, very challenging," Weissman said in an interview in his office, surrounded by furniture all made in his factory. "We're lucky if we put an ad out there, if we get five or six responses."

And, of those five or six, he insists not all of the applicants will pass a drug test or have a consistent work history.

Weissman says people don't want to stand on a production floor for eight to 10 hours a day, picking up a piece of wood and putting it through a sanding machine.

"But the work still has to get done," Weissman said. "We have customers that still expect to receive their product."

One day last year, Weissman had a backlog of customer orders to fulfill, and he was getting worried about whether his company would be able to meet the demand.

He began surfing the internet during lunch and came across news about a company called Rethink Robotics, whose mission is to create "smart, collaborative" robots.

Automation's Impact

Just the thought of a robot can trigger fears of job loss. And research says it's inevitable: Certain routine jobs will disappear because of automation.

Advertisement

"We live in a time where, not surprisingly, there are a lot of people, particularly in middle-educated and less-educated households, who have a lot of tasks that can be substituted for by a machine," said Michael Hicks, an economist and director of the Center for Business and Economic Research.

"Automation is likely to replace half of all low-skilled jobs," according to Hicks' recent research on the subject.

Hicks sees automation — in the long run -- as an overall boost for the economy. U.S. manufacturing, for instance, experienced a record year of output in 2015.

But for Hicks, the broader societal problem is that the people whose jobs are being killed aren't prepared for the new jobs being created.

Massachusetts, overall, is less at risk than many states in the industrial Midwest, according to Hicks' work. But it's not immune from these broad economic shifts.

Buying Robots To Keep Manufacturing In America?

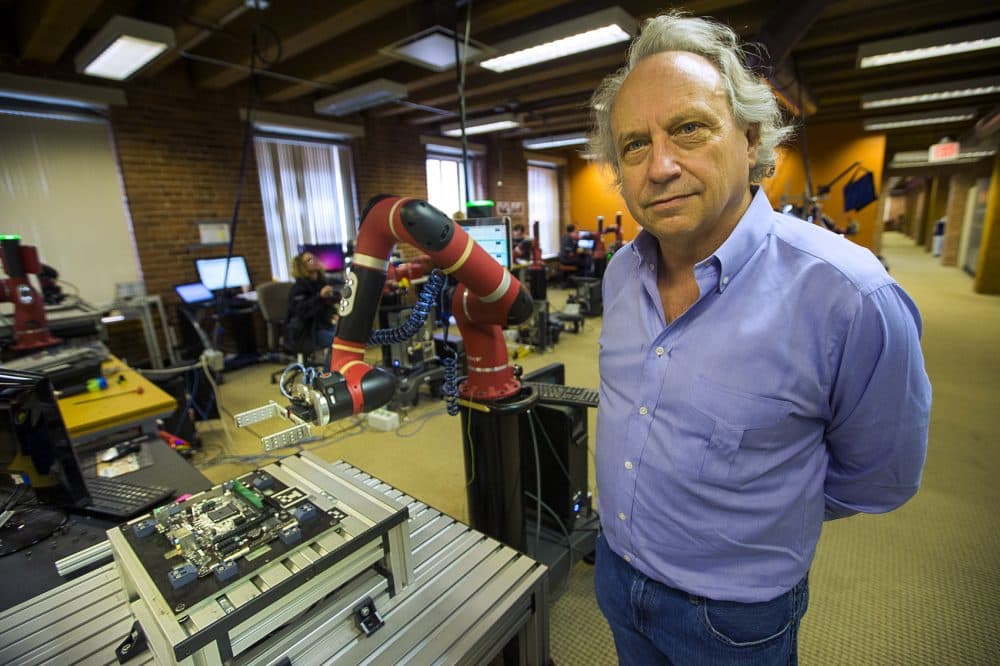

Rethink Robotics was founded in 2008 by Rodney Brooks, former director of the computer science and artificial intelligence lab at MIT and a co-founder at iRobot.

Brooks' goal with Rethink was to introduce more affordable options for automation, and in recent years, robot investment across the globe has grown rapidly. From 2014 to 2015, private investment in the robotic realm tripled, according to the Boston Consulting Group, and that's in part because of manufacturing.

Brooks is aligned with Moduform's Weissman — he, too, sees a manufacturing labor shortage. In fact, he laughs at the idea that politicians claim there's "not enough factory jobs."

"No, there's not enough factory workers," he insisted.

Hicks, the economist, is skeptical when he hears companies and executives say they have a labor problem. He says the issue is more about wages than workers.

"If you say you can't find people, it's because you're not offering enough for them to work there," Hicks said, speaking broadly about U.S. jobs and the labor market.

But for Brooks, this is actually a story about trying to keep American manufacturing in America. He makes his robots in the United States.

"We build robots in the U.S. and we export them to the rest of the world," he said. "People are not buying robots and firing people. Our customers in the U.S. are getting the robots so they can keep manufacturing here because they can't get enough workers."

Brooks doesn't think automation will replace human work, but he admits it will inevitably change how we work.

"I see letting the people, the workers in the factory, be the supervisors of the robots and using the robots as tools," said Brooks, pointing to engineers testing a robot at the Rethink office, an old warehouse in Boston's Seaport District.

As engineers calibrated the software, a red robotic programmable arm on wheels picked up a circuit board on a makeshift assembly line and put it down, again and again, on repeat. "Our robots do simple, repetitive tasks," Brooks explained.

The Robot 'Supervisor'

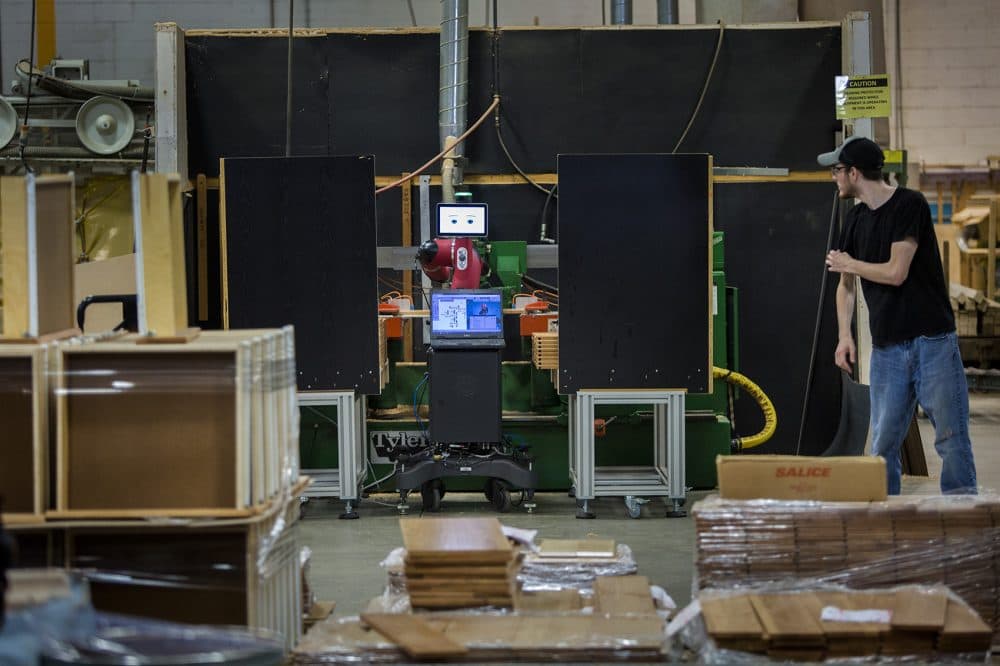

Weissman eventually decided to buy a Rethink robot, and it arrived on his factory floor this past spring. He said he paid somewhere between $40,000 and $50,000 for the robotic arm. And he uses it for one main repetitive job: picking up a piece of wood, putting it in a machine, letting the machine run, and then pulling it out.

"It's picking the drawer front up and it's feeding it into the machine that's actually cutting and routing those dovetails," Weissman explained over the loud buzz of wood getting cut.

In the past, Moduform would have asked someone like Brandon Correia, 23, to operate the machine by hand.

"I started working here over the summer, just as a plain factory worker," Correia said. "[And] sometimes, I would work this," he said, pointing to the machine the robot was feeding. "It's boring, very boring. It gets very old, very quickly."

When Weissman first purchased the Rethink robot, Correia was asked to set it up.

"This was really the first time I've ever tried to program anything like this," Correia said. It wasn't easy, but he said he eventually figured it out, and now can set different programs for individual drawer sizes. He's essentially become the robot's "supervisor."

"I'll come back after a half hour, make sure that it's working, make sure everything's going OK," Correia said. "And then I'll come back when it's done. And make sure there were no errors."

This one little robot has changed the nature of his job. "This eliminates that whole human operator," Correia said. He says having a robot pick up the "tedious" work frees him up to do other jobs.

He acknowledges that it's possible one day companies could buy an army of these robots and need fewer workers. But for now, he says you still need people to program and supervise the automation process.

Correia is kind of a rarity in this factory: He's 23. The average worker at Moduform is over 50. And Weissman is worried about his aging workforce.

He says automation might make his factory jobs more desirable to a younger generation.

"When I saw the robot, one of my thoughts was, 'Geez, you know, what if I was advertising for a robot manager. And their job was pretty much to plan the work for a handful of these machines,' " he said. "That, to me, would be the type of career a younger person might be drawn to because they get to use computer skills."

And even if it isn't, Weissman says he needs to figure something out, because he needs a younger workforce to keep his business alive in the long run.

This segment aired on November 1, 2017.