Advertisement

Secret Suffering: Teens With Endometriosis And Years Of Baffling Pain

For Emily Hatch, the pain started during a Taylor Swift concert in the spring of 2010.

During the very first song — "You Belong To Me" — and without any warning, Emily, then 13 years old, felt a stabbing pain below her belly-button unlike anything she had ever experienced. She clutched her stomach and doubled over, but that didn't help. Before the song ended, she was rushed by wheelchair to an infirmary at the Boston stadium and her father was summoned to drive her home. "The pain was so bad I couldn't stand up," Emily recalled. "It was so sad because I'd been looking forward to the concert all year."

That was the start of a medical odyssey in which the teenager from Wellesley saw seven specialists, underwent numerous invasive tests including a colonoscopy and endoscopy, and endured countless needles and scans of her body. Despite all that, her mother says, her underlying diagnosis eluded top experts at three major hospitals. At least one doctor told Emily she'd just have to live with the terrible pain. And while she was shuttling between doctors and missing school, Emily tried to keep her condition a secret, not telling friends because, well, she's a typical teenager. "I just didn't want to feel different," she said.

Finally, after 18 months without a firm diagnosis, Emily and her mother, Mary Alice Hatch, found a doctor in Boston who was able to treat her.

In October, at age 14, Emily underwent surgery at Children's Hospital Boston and only then learned she had Stage II endometriosis. Emily's surgeon found significant red and white lesions in her pelvic cavity; her left ovary had effectively become fused to her pelvis. Today, she is still not entirely pain-free, but at least she knows what the problem is.

A Painful Secret

Endometriosis is often perceived to be a disease of adulthood. Years ago it was cast pejoratively as "a career woman's" condition that mostly hit older women who had delayed child-bearing. But in fact, endometriosis frequently begins in adolescence. It can be passed genetically from mothers to their daughters; there is no cure.

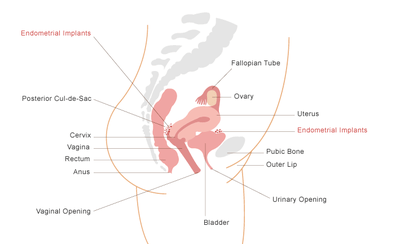

Endometriosis occurs when cells that normally grow in the lining of the uterus (endometrial cells) start growing in other parts of the body: the abdominal cavity, ovaries, fallopian tubes, bowel, bladder or the area between the vagina and rectum, for instance.

In rare cases these cells have been found growing in the brain or lungs.

This misplaced tissue, unlike normal uterine lining cells, has no pathway out of the body during menstruation. The resulting lesions can become intensely painful and cause scarring, inflammation, bowel and other problems. Advanced endometriosis can result in infertility.

The causes of endometriosis remain a mystery, and the growths generally can be detected only through surgery. Experts don't know if women are born with these cells in the wrong location, whether the cells actually migrate or if the condition is caused by some disorder of the immune system. "One theory," notes an NIH website, "is that the endometrial cells shed when you get your period travel backwards through the fallopian tubes into the pelvis, where they implant and grow."

More than 6 million women in the U.S. suffer from endometriosis, according to rough estimates. And though most women with the disease say their symptoms started before the age of 20, endometriosis, while common, is greatly under-diagnosed, particularly in teenagers. No one knows exactly how many teens suffer from the condition but according to the medical website UpToDate, the "disease has been reported in 25 to 38 percent of adolescents with chronic pelvic pain."

And because it falls under the rubric of "women's troubles" — even worse, teenage-girl troubles — it can take patients and their families years to get the right doctor to pay attention.

Advertisement

In that regard, Emily's case is not atypical. "Unfortunately, people don't realize that this can affect young girls," said Emily's doctor, Marc Laufer, Chief of Gynecology at Children's Hospital Boston and the Center for Infertility and Reproductive Surgery at Brigham and Women's Hospital."

Consider these numbers from one 2004 study:

- "Forty-seven percent of the women reported having to see a doctor five times or more before being diagnosed or referred. Those with the earliest onset of symptoms had to see the most doctors to reach diagnosis..."

- "Overall the delay between onset of symptoms and actual diagnosis of the disease was 9.28 years. Part of the delay was that the girl/woman took 4.67 years, on average, to report her symptoms to a doctor. Subsequently, the doctor, on average, took 4.61 years to diagnose the disease."

In financial terms, one analysis estimated that endometriosis cost the U.S. $22 billion in 2002, including hospitalizations, loss of work, surgery, and medications.

Falling Through The Cracks

Adolescent endometriosis tends to fall through the cracks for several reasons, said Dr. Laufer. First, he says, many gynecologists aren't comfortable performing surgery on 12-, 13- and 14-year-olds and there simply aren't that many pediatric gynecologists in the country. Laufer, an internationally known expert on adolescent endometriosis, performs five or six such operations weekly.

Also, he says, the population that suffers from the condition is not prone to trumpet their intimate problems to the world. "It's a disease that affects young women, specifically, adolescents who don't know what the norm is. They don't want to complain; it's an age where you don't want to feel different or stand out. If you're having pain and can't participate in gym or school, you don't want to complain, you just deal with it."

That's what Emily intended to do, but her pain became unbearable.

After the Taylor Swift emergency, Emily's mom made an appointment with the pediatrician. The doctor couldn't pinpoint the source of the pain, but suggested it might be a gastrointestinal problem.

A Mom Goes Online

Unsatisfied with such a murky non-diagnosis, Mrs. Hatch did what many mothers do when their child is suffering inexplicably: she went online. There she found a top GI doctor at Children's Hospital Boston. He examined Emily, ordered an upper endoscopy and said she was suffering from Irritable Bowel Syndrome and suggested some dietary changes, Mrs. Hatch said.

Undeterred, Mrs. Hatch took Emily to see another top GI doctor, this one at Massachusetts General Hospital. After a battery of tests — X-Rays, an MRI and a colonoscopy — the MGH physician put Emily on two medications and sent her home, but, Mrs. Hatch said, her daughter's pain just kept getting worse.

In July, 2011 she decided to fly with her daughter to the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn. to seek yet another expert opinion. "My family has given big grants to Mayo Clinic," Mrs. Hatch said. "So we have that connection." (Mrs. Hatch comes from a prominent family: She is the granddaughter of J.W. Marriott, the hotel-chain founder, and the daughter-in-law of U.S. Sen. Orrin Hatch.)

Their planned 4-day trip turned into a two-week nightmare after a Mayo Clinic GI specialist told Emily she had a "pelvic floor disorder" and prescribed pelvic muscle exercises three times a day, Mrs. Hatch said. This, says Emily, caused horrible constipation, and little relief.

By this point, no one had suggested that Emily see a gynecologist; Mrs. Hatch said it crossed her mind since the pain had started right after Emily's first period. So she asked to see a gynecologist while at the Mayo Clinic. At the appointment, Mrs. Hatch raised the possibility of endometriosis because a friend had mentioned it in passing. But, she said, the Minnesota gynecologist was non-committal. "She said, 'You could try birth control pills and see if the symptoms subside.' But she wasn't definitive."

A $16,000 Bill But No Answers

All told, the travel and medical bills for the Mayo Clinic trip were $16,000, which Mrs. Hatch paid out of pocket. But, she said, "I had a sinking feeling about the whole thing."

Meanwhile Emily, who by now had finished 8th grade and was about to start high school, continued to endure excruciating pain.

"It was really frustrating," said Emily, a sweet, sandy-haired young woman, who told me her story at the dining room table of her home in the Boston suburbs, offering up her favorite gluten-free popcorn and downplaying her ordeal in typical teenage fashion. Of her initial pain at the Taylor Swift concert she said: "It was quite terrible — not going to lie. But I get to see her music videos on YouTube, so all is well."

Over the course of one year, Emily missed three months of school and had to go home early every day. She was forced to quit soccer and curtail her other favorite sports.

"I was constantly in pain, all day, everyday, there wasn't a full day where I just felt great," Emily said. Still, she kept her condition a secret. "A lot of my friends didn't know I had this," she said. "I just didn't want to feel different. High school is really judgmental. You tell one person something and it just spreads."

(After speaking with me, Emily had second thoughts about going public with her condition, but ultimately decided that she wanted other kids to know more about it, so they might avoid enduring what she did.)

For Mrs. Hatch, the lack of a definitive diagnosis and a clear treatment plan was particularly troubling. "It was so isolating," she said. "You wonder, 'Am I doing the right thing?' I mean, this is affecting her socially, mentally, physically, and as a parent you feel helpless: you're doing everything, you're going to the best doctors, and you still can't get an answer."

Before Mrs. Hatch put her teenager on birth control pills, she took Emily to yet another specialist at Children's Hospital. Again, the response was demoralizing. Mrs. Hatch said that doctor told Emily she was experiencing "functional pain," a sort of phantom phenomenon in which earlier pain has actually subsided, but the nervous system still fires off pain signals. Mrs. Hatch said the doctor told her daughter she'd just have to "learn to live with her pain."

A Clear Diagnosis

Given the medical impasse, Mrs. Hatch decided to find a pain therapist. Almost immediately after she got one on the phone, the doctor said: "I think your daughter has adolescent endometriosis. You need to go to a gynecologist."

Emily and her mom describe their initial interactions with Dr. Laufer, the Children's Hospital gynecologist, as filled with an almost magical good karma. Laufer was the first name to come up in Mrs. Hatch's Google search; then, after their first meeting he had a cancellation at the last minute that got them on the surgery schedule. Finally, on the drive to town: "We hit all the green lights going in to Boston — that never happens," Emily said.

Laufer performed the surgery laparoscopically, making two incisions, one in Emily's belly-button, the other just above the pubic region. The goal of the surgery is to remove all of the lesions, even the subtle ones. Shortly after he was done, in less than an hour, Laufer announced the diagnosis: Stage II endometriosis. "We can't cure this disease," he said. "But our goal is that a woman be completely functional, and can compete in all activities — equal to men — so they don't feel disadvantaged."

Now, Emily takes hormone pills that prevent her from getting her period until she wants to have a baby. To control her pain flare-ups, Emily continues to do physical therapy, and visits the Children's Hospital pain clinic three times a week. Her regimen also includes Reiki, a technique for stress reduction, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and acupressure. "I think all of this does help, because it relaxes her body, and allows her to better deal with the pain," her mother says. "But it's a brutal disease."

After the surgery, Mrs. Hatch approached Laufer, who also oversees an annual conference on endometriosis for teenagers and their families to share stories and new data, and asked what more she could do to help hasten research that might ultimately lead to a cure for the condition. "I asked him what his dream would be," Mrs. Hatch said.

She said she then approached her father and uncle, who run the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation, which gives money to a variety of causes, including in the medical arena, to see how the organization might support future endometriosis-related research. Stay tuned for more on that soon.

Emily will probably continue to struggle with some level of pain for years. Still, she says, understanding her condition and continuing treatment have been critically important. "I had never heard of endometriosis before...and a lot of people don't know about it," she said. "There have to be some people who are open about this so they can influence others to go see a doctor. If I can help girls out there like me, I might as well."