Advertisement

When You Lose Your Sport, What Happens To Your Self?

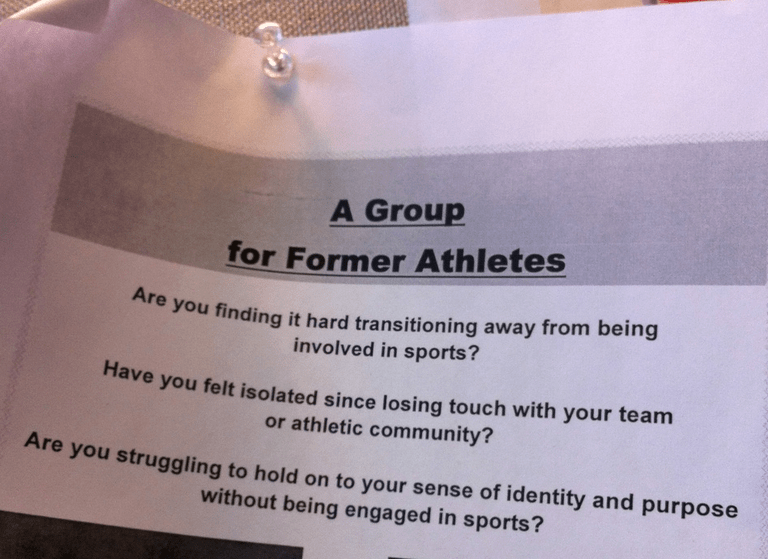

I saw this flyer recently on my gym's bulletin board. The loneliness and loss of identity it describes are surely shared by a great many people who have to leave sports, famous or not, but what comes to mind is the suicide of Junior Seau, the 43-year-old former NFL player who shot himself in the chest last week.

Much of the coverage has focused on the possibility that Seau, like many other football players, suffered concussions that wrought permanent damage to his brain. But what struck me most were the descriptions of him as a player — upbeat, intense, loving the game — and then his life after retiring: He drove his car off a cliff in 2010. His girlfriend told police he assaulted her.

“I’m sorry to say, Superman is dead,” said San Diego Chargers chaplain Shawn Mitchell after Seau's suicide, according to The Associated Press. “All of us can appear to be super, but all of us need to reach out and find support when we’re hurting.”

Finding support is the idea behind the therapy group that Dr. Matthew Krouner, the Brookline post-doctoral fellow in clinical psychology who posted that notice above, is aiming to put together.

It would not be only for elite athletes, he said. "This group could be for anybody who has at one time identified themselves as an athlete. It could be high school, it could be they like to run marathons, it could be they play pick-up basketball once a week. But once you're not able to do that anymore, even if it's not a professional identity, there's a real sense of loss and a grieving that can take place. For elite athletes, the transition out of sport is conceptualized as a loss or grief experience."

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'For elite athletes, the transition out of sport is conceptualized as a loss or grief experience.'[/module]

Dr. Krouner never had a stellar sports career himself, he says, but always played, and had long been fascinated by stories of pro athletes whose lives deteriorated after they retired from sports at young ages, when many people are just starting their careers. They had to face the monumental challenge of losing an "all-encompassing identity — it's how you relate to other people, it's how you use your body, it's your mental stimulation."

Athletes have become more open in recent years about mental health issues, reducing the stigma. So "it seems like a good time for more supports to be out there," Dr. Krouner said. "There tends to be a sort of expected toughness factor among athletes and that may make them less likely to seek out mental health resources, but hopefully by putting more and more out there, it can appeal to the need that is present."

That need is very real, said Justine Siegal, director of sports partnerships at Northeastern University's Sport in Society program and a doctoral candidate in sports psychology there.

Plan the exit well in advance

It is estimated that about 20 percent of athletes need "considerable psychological adjustment" after they leave the sport, she said.

"They face challenges with their athlete identity: Who am I if I'm not an athlete? Your peers change because you're not with the same group. Your body changes and it often becomes less fit."

"You don't necessarily have a plan outside of your sport," she added, "and that can be very disconcerting, to be so goal-oriented your whole life and then just have to walk away and move on to a new goal. When you haven't planned out what that goal is, you can feel lost."

In other spheres of intense endeavor — finance, say, or medicine — a professional who is forced out of a job can usually find another, but 'When football's over, it's over," said Scott Farley, a former player for the New England Patriots and Carolina Panthers. He was forced to retire in 2006 after he tore his hamstring all the way "off the bone."

He tried to come back to football, but his body simply wouldn't allow it. A few months after the injury, he fell into a depression. "It's losing something that's really important to you," he said. "It's like the rug being pulled out from underneath you."

"There's a loss of identity after you're done playing sports," he said, "because you obviously identify yourself as a competitor, as an athlete, someone who thrives on the competitive and euphoric nature that comes with the sport you're playing." And then, if you go pro, the sport gets even more important: It becomes your job at the same time.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'It's an activity you do but it’s not who you are.'[/module]

"Having somebody else — namely, my body — decide that the game was over for me, that's certainly something that, while playing the game, you don't think about," he added. "You're playing in the moment, your mind is in the moment, and you don't really think about long-term objectives."

But you should, Justine Siegal said. It is key to begin "exit" planning well in advance, "always knowing that at one point, you’re going to have to leave the sport. Unfortunately, the old school coaching is to let them completely focus on their sport, and when they do that, that means they're not preparing for a world outside their sport."

Counseling can also really help, she said, "exit counseling" and group counseling with other athletes who are making a transition, teaching them how to transfer their sport skills — goal-setting, time management, stress management — into life skills.

"Unfortunately, there's not enough counseling groups," she said. "There should be more."

Matthew Krouner says that one of his hopes for his therapy group at the Brookline Community Mental Health Center is that it could become, in a sense, its former athletes' new team. "They could be learning how to support each other and rely on each other, that's part of why I thought the group modality would be helpful," he said.

Dr. Krouner's idea makes sense, Scott Farley said. "Whenever you get a group of people together that can share similar experiences and feelings with each other, it can help you sort through your own thoughts," he said, "and give you the feeling of not being alone in the struggle."

Dr. Krouner said members could also share experiences on what works well for them and what doesn't. He's aiming for a set of ten weekly evening sessions for a $300 fee that would also include an initial individual evaluation.

A more holistic identity

Dr. Chris Carter, director of behavioral medicine at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, compares the jarring dislocation of leaving sports to retirement from the intense, mission-oriented work and camaraderie of the military.

How well a person does, he says, can depend on how "well-grounded" their identities are.

"If the main and only sources of self-esteem they have, or pride, or relationships, or notions of how to be successful, are tied in to their athletic ability, and now they can't compete, they're going to have a much more difficult time adjusting than the individual who's more well-rounded," he said.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'It was fun while it lasted. But now it’s time to do something else.'[/module]

Being better-rounded, he added, means that "Athletics is part of what they do but not the only thing they do. They can come to the point of saying, 'I had a great run. It was fun while it lasted. But now it's time to do something else.' That's the basis of character: How do you roll through and adjust when life changes on you like that?"

As Justine Siegal put it, it's important to have a more "holistic identity." To know that "you are the same person whether you’re on or off the field. It's an activity you do but it’s not who you are."

Research bears out the idea that athletes transition out of sports better when "they have a sense of themselves outside of just being an athlete," Dr. Krouner said. "That's important for coaches at all levels to be really realistic about."

Of course, athletes facing retirement can always ease the transition by becoming coaches or trainers themselves. That's what Scott Farley does now, specializing in fitness performance at Beacon Hill Athletic Clubs. "The gift of giving back to others is what helps me feel good about what I'm doing on a regular basis," he said.

Former athletes can "give back to the sport" in many ways, Justine Siegal said, "whether as a coach, administrator or volunteer. It keeps you in the game and you’re helping other people to enjoy it, especially children. I think there's nothing better for healing than seeing a child love doing something you both love."

This program aired on May 11, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.